AS I WALKED out of the screening room where I had just been afforded a track fan’s treat, a sneak peak at Czech director David Ondříček’s new film Zátopek, another audience member commented on the T&FN t-shirt I happened to be wearing.

AS I WALKED out of the screening room where I had just been afforded a track fan’s treat, a sneak peak at Czech director David Ondříček’s new film Zátopek, another audience member commented on the T&FN t-shirt I happened to be wearing.

Appropriate viewing attire, he observed, for a biopic on the famed “Czech Locomotive,” who set the track alight at the Olympics of ’48 and ’52 to the tune of four golds and a silver, including his tour de force sweep of the 5000, 10,000 and marathon in Helsinki.

“I kept waiting to hear the Chariots of Fire soundtrack,” joked my affable fellow film watcher. Ha ha. The all-purpose track movie cliché.

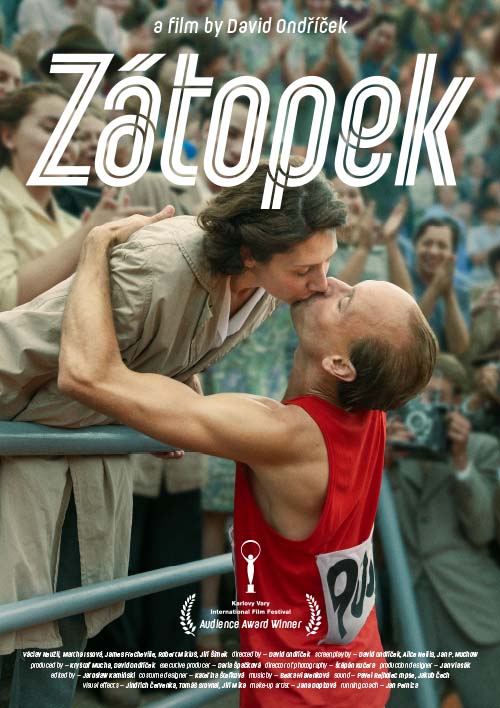

However, the quip underscored a point about Zátopek, in which Václav Neužil plays the notoriously hard- and quirky-training distance great, and Martha Issová his Helsinki javelin gold medalist wife Dana Zátopková. The film steers adroitly, absent a heavy hand, past the snares of cliché that inevitably lie in wait when a sports story is adapted for the screen.

Ondříček — the son of noted cinematographer Miroslav Ondříček (O Lucky Man!, Ragtime, Silkwood, Amadeus) — with co-writers Alice Nellis and Jan P. Muchow slips away from the obvious story arc through a device track fans in the know will appreciate.

Rather than tread dutifully from our hero’s weak-lungs diagnosis as a child through the early Cold War toward Zátopek’s brilliant and as yet unmatched Helsinki triple, the film, which jumps back and forth in time, begins near the end of its timeframe — with an autumn ’68 pilgrimage by Aussie distance great Ron Clarke (James Frecheville) to Zátopek’s home in Prague.

Dramatic license is taken. The storied visit by Clarke — Zátopek’s WR-smashing cognate of the ’60s — actually seems to have been in July of ’66.

In any case, the movie Zátopek is a decade-plus retired and the two bond emotionally amid the Aussie’s frustration with his repeated failed grabs for Olympic gold. This deeply personal connection, as evidenced by many Clarke retellings, certainly blossomed for real.

Dana is absent initially and the hint is at marital difficulties — a theme throughout the film alongside the couple’s passionate love for each other that figured prominently in contemporary news accounts and the Zátopek legend.

The onscreen chemistry between Issová and Neužil captivates, perhaps aided by an aspect of real-life chemistry bubbling in the crew. Issová is Ondříček’s wife and played an integral role as the director met with the real-life Dana and worked to win her trust. Zátopková passed away at 97 in March ’20, just over a year before the film’s Czech release.

“Dana Zátopková didn’t want to give us permission to make the film,” say Ondříček, who also directed a 2016 TV documentary treatment of the drama’s central figure, “but after I met her a few times and I brought a few bottles of red wine, she changed her mind very soon and she saw that we wanted to make the true story.

“It was most important for her because she had a lot of bad experience with media and with politics.”

Dana’s reluctance should surprise no one. Zátopek was a lieutenant colonel in the Communist Czechoslovak army and the premier sporting icon of his nation, but he butted heads with the regime as early as ’52 and eventually fell into blacklisted disfavor after publicly condemning the post-Prague Spring Soviet invasion of ’68.

Anyway, Dana bonded with the filmmaker couple. “Martha, my wife, she was the only one person [on hand] on Dana’s 97th birthday [in ’19],” Ondříček reports, “and they celebrated it together. I can say that they started to be very close friends.”

One wonders if Clarke, Dana or the filmmakers imaginations served up the detail of a Helsinki Olympic javelin repurposed in the Zátopek apartment as a broom handle?

Also in play on the screen as Neužil’s witty yet engagingly enigmatic Zátopek alternately frustrates, puzzles and charms Clarke is the age-old question: is winning what matters or is the greatest value in having striven with every fiber of one’s will, work and talent?

What was Zátopek’s take on the question? This movie plays all the better by persistently rephrasing the question but never wrapping up a pithy answer.

This writer had the great fortune to be invited to an intimate group dinner with Zátopek some 30 years ago. He exuded easy-going charisma, humor and humanity, as I expected from all I’d ever read or heard about him. He ordered a Budweiser — the American frosty beverage of that name, not the Czech — with Italian food. He told stories of his life and his running.

Still, though, his celebrity athlete life lived mostly — and for a time silenced by power — on one side of a politically curtained world was hardly a wide-open book. Even to Czechs. Zátopek’s resistance to packaging the man too tidily hits a note to be respected.

Rec to track fans with a history bent: Check out this movie.

While staying away from spoilers here, we know you must wonder, does Neužil pull off our hero’s one-of-a-kind appearance and his rarer still running style?

Surely you know his tortured form. On the off chance you don’t, here is Zátopek’s initial T&FN appearance in a first-hand race report — on his ’48 Olympics 10K win (T&FN, August ’48):

Then, suddenly, the lead was taken by an awkward Czech in a faded red shirt and thinning, corn-silk hair. Zátopek, the Human Locomotive, the greatest all-round distance runner in the world.

Zátopek looks anything but great. He puffs and blows, makes frightening faces, looks back every few yards, and hunches his shoulders painfully. About every third step he reaches his right arm down as if to scratch his leg.

Many an observer since has pointed out that below the waist Zátopek’s form was nothing if not a relentless roll toward the finish line.

Still, even with TV not yet a thing 73 years ago, what fan could have resisted fascination with such a figure?

Actor Neužil faced the more prickly challenge of resembling it — and got about as close to the mark as a mortal might. He had plenty of time as the movie project crawled for some 15 years while Ondříček and producer Kryštof Mucha chased funding.

“He’s a very talented actor and he’s a very good sport looking character, which is not so common in the Czech Republic,” Ondříček says of Neužil. “I made some running rehearsals with him, I just showed him on the iPad. And unfortunately it looked terrible. That was 13 years ago, and I sent it to a professional athletics coach. Surprisingly, he called me back and he said, ‘He will be all right. He will be prepared to play Zátopek, but it will take one or two years.’

“And after six years he really looked like Emil Zátopek and we were ready to shoot the film. Honestly what he did for this film — from my perspective, it’s more his film than anybody else’s because he really did something amazing.”

Of note for track history buffs, as well, is more than solid reproduction of period stadia — iconic stadia that were Olympic sites, including Mexico City’s where we first encounter Clarke collapsing at the 10K finishline.

Whether at Wembley or Helsinki, you’ll not find anything today that resembles the edifices of ’48 or ’52. Ondříček and crew improvised, doubling a crumbling arena at Brno in the Czech Republic for four different stadium settings in the film. The effect, with generous reliance on green screen in post-production is convincing enough.

The film’s look and color palate also effectively evokes the Cold War era. The wise choice was made to subtitle, not dub, all non-English dialogue.

What’s more Zátopek cost just $5.3 million to make, a bogglingly low price tag for a period film spanning three decades. For comparison, consider that the 1994 Pre biopic Without Limits had a $25 million budget — 27 years ago. Just another creative flourish to recommend this film.

Having premiered at the Karlovy Vary Film festival to great home country acclaim in August, Zátopek currently is the Czech Republic’s submission for Academy Awards Best Foreign Film consideration. U.S. theatrical distribution is expected early in ’22 with streaming a sure thing on the further horizon.