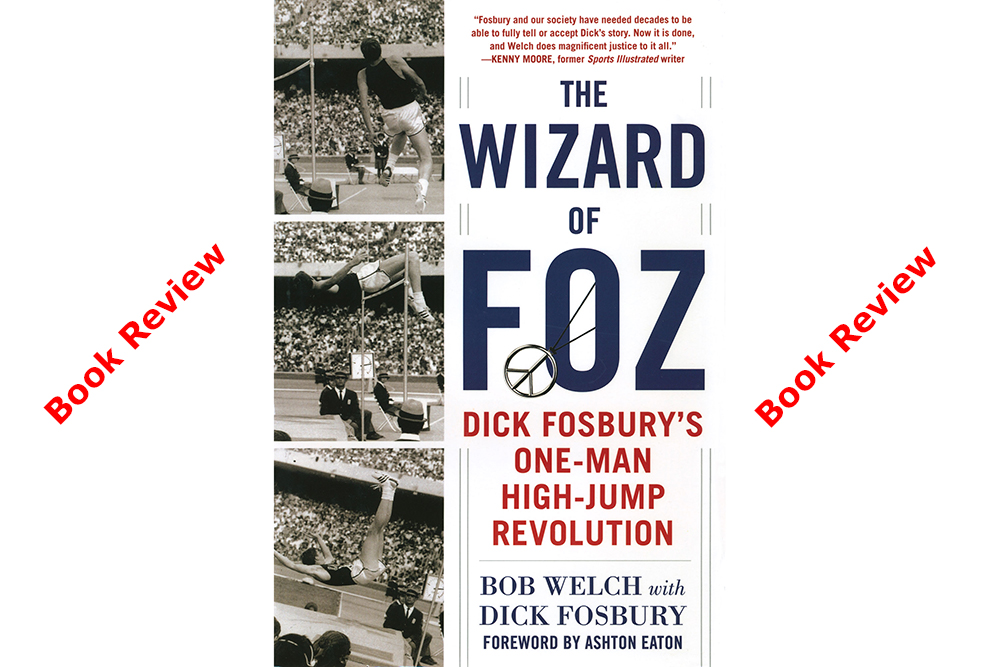

As October brings us the 50th anniversary of the Mexico City Olympics, we are seeing a number of books that transport track fans back to that memorable time. We previously reviewed Bob Burns’s The Track In The Forest and Wyomia Tyus has a new memoir out that we’ll get to soon. And then there’s the amazing story of the man who revolutionized high jumping—Dick Fosbury—as chronicled by Bob Welch.

As a Medford, Oregon, 9th grader, Dick has described himself as “one of the worst high jumpers in the state of Oregon.” Using the straddle—the commonly accepted “proper” high jump technique of the time—he had a personal best of 5-4 (1.62). Out of desperation, he reverted to the scissors style at one meet, a style to which he added a back layout to get his rear end over the bar, and the Fosbury Flop was born. By the time he was a senior he had upped his PR by more than a foot and finished 2nd at State.

Though spectators were fascinated by Dick’s crazy backward style, there were many naysayers particularly in the coaching fraternity: “the kid will break his neck” (remember—in many places jumpers were still landing on a pile of wood chips or sawdust at that time), or “the back layout style has an upper limit lower than the straddle.” But mainly they had no idea how to coach it. As an entering frosh at Oregon State, Dick would be coached by Berny Wagner, who was in his first year at OSU. Berny didn’t really know what to do with Dick, and he tried to get him to switch back to the straddle, a form he was comfortable coaching.

But there’s nothing like success, and in his sophomore season, ’67, he raised his PR to 6-10¾ (2.10), and placed 5th at the NCAA. Coach and athlete were now on the same page.

There are just so many elements to the Dick Fosbury success story:

•If WR holder Valeriy Brumel hadn’t suffered a horrendous motorcycle accident in ’65, essentially ending his career, he would undoubtedly have been the ’68 gold medal favorite;

•If Don Gordon hadn’t come along in the early ’60s and developed the foam pit that would become Port-a-Pit, would Fosbury have been able to risk those higher heights on a wood-chip pit?

•If Fosbury hadn’t cleared a PR 7-3 (2.21) at the Olympic Trials when trailing in 4th, he wouldn’t have been at Mexico City to astound the world with his unorthodox form and the Olympic Record height of 7-4¼ (2.24). He ended up No. 1 in the T&FN World Rankings for the year.

The revolution was quick. The next Olympics, Munich ’72, saw the last straddler to win Olympic gold—Jüri Tarmak. Even at those Games, 28 of 40 jumpers were floppers. By ’79 the revolution was complete; straddlers had become obsolete. Now that’s innovation!

Author Bob Welch tells the story well—the loss of Dick’s 10-year-old brother in an awful bicycle accident, his parents’ divorce a few years later, his failures at other sports, the anxieties of the time—particularly Dick’s fear of being drafted and sent to Vietnam, the post-Olympic malaise when jumping didn’t seem as important, though he did manage to win the ’69 NCAA title and earned his second—and last—World Ranking spot, a No. 5. He was offered a chance to finish his engineering degree, and he accepted eagerly, though it essentially meant giving up high jumping.

Genius, innovator, pioneer, revolutionary—Dick Fosbury would undoubtedly balk at these epithets. From his standpoint, he was just a regular guy trying to find a way to succeed at an enterprise he loved.

Other people had gone over backwards at about the same time Fosbury did, notably Canadian Debbie Brill with her “Brill Bend.” But he experimented and perfected a new style and reached the very pinnacle of his sport. There’s genius in that.

The Wizard Of Foz: Dick Fosbury’s One-Man High-Jump Revolution, by Bob Welch, with Dick Fosbury. Foreword by Ashton Eaton. Hard cover. 262pp. Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., NYC, NY. $24.99