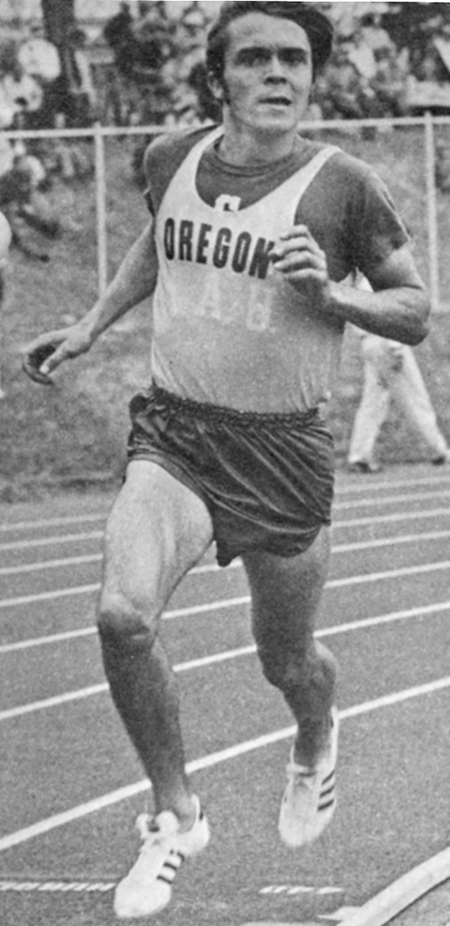

HERE, IN THE SEVENTH chapter of a long multi-part series, is how we reported the career of Steve Prefontaine in the summer of ’72, with the same photographs we used at the time. We have taken the liberty of doing some stylistic updatings to mirror our modern protocol and also added an editorial comment or three:

I July 1972: Prefontaine Churns Out 7:45.8 U.S. 3000 Record

Gresham, Oregon, June 24—Steve Prefontaine wasn’t surrounded by his adoring Eugene fans but he ran at the Rose Festival meet as though he was right at home. The result: an American 3000m record 7:45.8, axing over 8 seconds from Jim Beatty’s decade-old 7:54.2 clocking.

Pre agreed to run this distance, seldom-contested in the U.S., because, “I didn’t want to run the heavy traffic in the 1500 nor did I want to run the 5000, the same distance I’ll be running in the Olympic Trials.”

This quick run only 5 days before the Trials begin shouldn’t bother the U.S. 5000 recordman since the 5000 trials and finals are not until the second week of the Trials. While the Portuguese Tables rate this time a second slower than the U.S. 2M record of 8:22.0 and the all-time list puts him fourth-fastest, the time was well off Kip Keino’s ’65 world standard of 7:39.6. It also topped the college best (8:07.6, Conrad Nightingale, 1967) by over 20 seconds.

Pre wanted a fast pace, specifically 4:10 to 4:12 for the first mile, so ex-Oregon miler Jere Van Dyk obliged with pacesetting chores. He and Pre cruised past the mile in 4:13, after which Van Dyk dropped out. But Pre put his head down into the drizzle and cold wind which doused the meet, witnessed by some 3000 spectators, and ran away from the field. Covering the final halfmile in approximately 2:02, Pre came home 6.4 seconds faster than Beatty’s record and over 15 seconds ahead of runner-up Greg Carlberg. Howell Michael was nearly 10 seconds behind Carlberg’s 8:02.6.

“I wanted to get under 7:47,” Pre said later, “so I was happy with the way things turned out. The record was ready to go anyway.” /Don Jacobs/

II July 1972: The Olympic Trials 5000

Eugene, Oregon—At some time on Thursday, July 6, it began to take shape as America’s greatest distance race of all time. Consider:

(1) Local hero and national record holder Steve Prefontaine was so full of nervous energy that he ran his heat in 13:51.2, then actually ran instead of jogging during his warmdown. He said, “I felt great today”;

(2) George Young ended speculation about his intentions by entering the 5000 after the training month of his life. The 34-year-old triple Olympian ran an easy 14:11.6 to qualify fifth in the slower heat and said, “I’m as excited about these Trials as I’ve been about any of the other three I’ve been in.” About Prefontaine, he said, “If I get 2nd here, I’m going to try to beat him in Munich”;

(3) Tracy Smith, ’68 Olympian who began a comeback a year and a half ago, ran 13:52.8 in Pre’s heat and said, “I’m not ready for a World Record, but I think I’m ready for 13:20. I want the pace to be hard”;

(4) Gerry Lindgren, fighting off his latest injury, ran 13:53.6 and said, “The winning time might be 13:20. The last mile will be murder… I’m optimistic”;

(5) Sid Sink, a great but disenchanted steeplechaser with the equipment and training to improve on his 13:11.0 in the 3M, looked confident in 13:58.4 and said, “I think there are four or five of us who have a real good shot”;

(6) Len Hilton, tenth-fastest 3-miler in world history, was picked by some experts to make the team because of his 3:57.6 mile speed;

(7) Greg Fredericks, a sensational finisher in the AAU meet, coasted to the slowest qualifying time, 14:19.2, and appeared ready;

(8) the heat broke, promising ideal running weather.

On Sunday, July 9, the weather was warmer than expected, and only two runners ran up to expectations. Lindgren led by 8y at the 880, then faded back through the pack and finished last. With Prefontaine 2nd in 2:09.6, the pack was well bunched past a 4:22.3 mile and 6:36.2 for 6 laps, where Pre led.

Then the race began to take on aspects of greatness. The average 440y lap had been 66 seconds, but now Pre ran 64.7 and the line of runners behind him began to lengthen. A lap in 65.1 brought Pre to the 2M mark in 8:46.0, and he led Hilton by 3y. Young moved to Pre’s heels with obvious determination, while Fredericks let go. Pre ran a 64.8 lap with only Young and Hilton close. Harrison was now 8y behind Hilton, with Smith another 10y back.

Now Pre began the task of breaking Young, one of the guttiest runners in track history. Pre ran a lap in 63.4 which dropped Hilton 25y behind, but the veteran Young held on grimly. With the crowd roaring, Prefontaine began a remarkable drive. A lap in 61.5 weakened Young and left Hilton 75y back, but Pre was only beginning. He increased the pace and opened an 8y lead with a lap to go. Young had to surrender, and Pre completed the lap in 58.7. His 3M time of 12:54.4 has been bettered only by Lindgren and Ron Clarke (twice).

With Young beaten, Pre slowed in the homestretch. Then he thought better of it and picked up for a respectable finish in 13:22.8, a time bettered only by Clarke (twice) and Dave Bedford’s 13:22.2. Pre’s last 440 was only 66.2 because of his homestretch “jog,” but his last 880 was 2:00.2, his last three-quarters was an impressive 3:03.2, and his final mile was in 4:08.6.

Young finished in 13:29.4, under Pre’s national record. Hilton was a safe 3rd in 13:40.2, equal to 12th on the U.S. all-time list but inferior to his 13:11.4 in the 3M. Sink, who had lagged too far behind, moved from 7th at 2½M, gained 20 yards on Hilton and missed the Olympic team by 25y in a PR 13:43.8. Fredericks seemed to lose his will when the pace quickened and never made a race of it.

Prefontaine, noted for his confident statements, said, “I have confidence now. I think that with proper training and rest I can go 10 seconds faster in Munich.”

Young was surprisingly unpleased with his performance. “I am disappointed. I should have gone faster. I need more races. I will be tougher at Munich.” /Cordner Nelson/

II July 1972: “Stop Pre” T-Shirts Excite “Go Pre” Fanatics

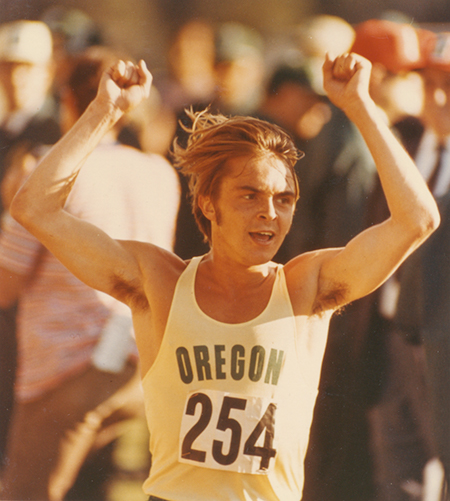

Newton’s third law of motion states: to every action there is an opposite and equal reaction. And even one of the country’s fastest moving bodies, Steve Prefontaine, is not immune. At the NCAA it was “Go Pre” t-shirts (see II June). A month later the track circuit moved back to Eugene for the Olympic Trials.

And what raised a lot of commotion there was “Stop Pre” t-shirts. Conceived as a put-on to the rabid Eugene crowd, the shirts featured a big red stop sign, with the words, “Stop Pre” emblazoned on the front. Carefully sequestered in the stands on the day of the 5000 final were 20 intrepid (or is it foolhardy?) fans, virtually unnoticed in their new accoutrements. But you couldn’t miss eager Gerry Lindgren promenading around the oval in his. The response was overwhelming. Now Gerry knows how the Christians felt in the Coliseum. But the response Gerry received was kind in comparison to that meted out to the perpetrators of the whole affair. Angry fans wanted to fight, meet management let it be known that it was not amused and some columnists made rather nasty comments concerning the rapscallions who would do such a dirty deed.

But all’s well that ends well. Pre won his race in fine fashion despite such hindrances, and at race’s end even accepted one of the shirts and put it on (which is what the whole affair was really about).

August 1972: Pacers Bedford, Pre vs. The Kickers

[Ed: In our Olympic Preview, 6 international experts—or “experts,” as we styled them—handicapped each event 6-deep. Pre was the consensus 5000 favorite, receiving 3 votes for gold, 2 for silver and 1 for bronze, but representing how tight things were, 6 different men were rated as “reasonable chance to win.” What follows is our thumbnail on Pre.]

Steve Prefontaine (U.S., 1/25/51, 5-9/145) has yet to demonstrate how good he is against the “big boys.” All indications are that he should be able to hold his own, thank you. Unafraid to force the pace, Pre has been criticized in some quarters for his lack of a fast finish. However, although his last 400s have been slow, his prolonged closing speed has sometimes been overlooked, e.g., a 4:08.6 final mile in his 13:22.8. And his recent 3:39.4 PR will rate him among the fastest of his competitors.

Self-confident to the point of cockiness, Pre will likely have the most positive mental attitude of those present. And, he is undefeated over the 3M/5000 distance since a last-lap lesson from Norpoth in July ’70.

September 1972 (OG 5000): Viren Waxes Foes Off Crazy Tempo

Just how great Lasse Viren is remained unproved, as the Finn who has everything completed the classic 5/10 double with a brilliant climax to a somewhat strange race. Apparently able to win off almost any pace—and at almost any of the longer distances—Viren was the best miler of the lot, clocking a final 4:01.2 as he drove to a slower than expected 13:26.4 victory. In doing so, he took everything a gutsy Steve Prefontaine could throw at him, striding home almost untired—looking to win handily from defending champ Mohamed Gammoudi, fast-closing Ian Stewart, and a run-out, tied-up Prefontaine. Despite the comparatively slowish result, the rest of a hot entry was strung out well behind or watching from the stands.

The skinny Finn (5-11, 134lb) takes his place alongside three other immortals of Olympic distancing, each of whom also won the double with class and a pair of Olympic Records. The first was the first of the great Finnish runners, Hannes Kolehmainen, in ’12. At 22 the youngest of the doublers, Kolehmainen also got a World Record (his was in the 5000).

Emil Zátopek, the Czech wonderman, did it in ’52 and added the marathon for a bonus. And the USSR’s Vladimir Kuts won a pair of great duels in ’56. A newcomer to the big time, Viren finished 7th and 17th in the European Championships last year although his 13:29.8 ranked No. 5 on the world list. But this season was another story. In the last few weeks before the Games, he whipped off races of 13:19.0, 27:52.4 and 8:14.0 for a world 2M record. Thus, he came into the meet as one of several favorites in both events, but still to prove himself in hot competition.

By the time the 5000 came around. Lasse no longer was one of the cofavorites in what everyone agreed was the competitive race of the Olympics. He was the favorite off his great 10-kilo win and because of the disappointing showing of Dave Bedford.

That favorite’s role was sharpened during the heats: 14 were to qualify, the first and second finishers in each of 5 races plus the 4 fastest other runners. This meant a fast pace in all the races. But someone forgot to tell those in the first heat. Bedford and Gammoudi clipped along at a decent enough pace—including a surging 2:37.5 third kilometer—had they had occasion to finish fast. But the others seemed unaware of the need to hurry and looked to be battling for third place, not for a fast time. As a result, the leaders eased in with a modest 13:49.8 while Ben Jipcho of Kenya and Swedish steeple ace Anders Gärderud threw away their opportunities by being content with 13:56.8 and 13:57.2.

In the remaining four heats it took better than Kuts’s Olympic Record to qualify. A baker’s dozen were under that 13:39.6 standard and all but one made it to the final.

Most of the fireworks were in the second trial as Pre and Emiel Puttemans tested each other before the Belgian edged ahead at the finish, as he had in the 10,000. He claimed a new Olympic Record of 13:31.8 with Pre a strong and confident 2nd in 13:32.6. As it turned out, Harald Norpoth of Germany and Javier Álvarez of Spain were quick enough to make it and Dick Quax of New Zealand was the chief casualty.

Heat No. III produced three qualifiers and featured a 55.1 last lap by Ian McCafferty. His 13:38.2 edged East Germany’s Frank Eisenberg and Norway’s Per Halle with well touted Tony Benson of Australia and steeplechasers Dušan Moravčík of Czechoslovakia and Tapio Kantanen of Finland eliminated.

Much of the interest in heat IV centered on Juha Väätäinen, who was so great in last year’s European Championships but who had run practically nothing this year. And when he won in 13:32.8, looking good, a new element was added to the final. This was the fastest of the heats through 4000m, at which time the first 8 runners were under Puttemans’ pace. But they strung out badly over the last kilo as Britain’s Ian Stewart (13:33.0) and the second half of the Spanish entry, Mariano Haro (13:35.4), won places.

The final section was as notable for the misses as for the makes. Viren and Nikolay Sviridov, USSR, had no trouble in 13:38.4, coasting in safely. Third went to Josef Jánský of Czechoslovakia, whose 13:39.2 was good enough to break the old Olympic record but not good enough to qualify. 4th was a heartbreak for George Young. The 4-time Olympian was ready for battle until injuring a hip just before coming to Munich. It killed his chances as two days before the race he couldn’t run a 70-second quarter. But George, who doesn’t understand what quit means, was in contention until the last 200m when his usual strong finish just wasn’t there. He was a disappointed 4th in 13:41.2. Two other goodies, Jürgen May of East Germany and Bronisław Malinowski of Poland, were far back.

And then there was Miruts Yifter. The Ethiopian 10,000 medalist somehow or other reported to the wrong gate, was denied admission to the track, and was left crying in the tunnel as the race started without him.

These casualties, the absence of Jürgen Haase, and the relative strengths displayed by the qualifiers combined to reduce the number of contenders going into the much anticipated final. But at least 9 of the 14 had to be watched carefully, although Viren, with recent World Records at 2M and 10,000m bracketing this distance, had to be the top choice. Also high on everyone’s talk list were Gammoudi, Puttemans and Prefontaine, veteran Norpoth, the English duo Stewart and McCafferty, Haro, and the comebacking Väätäinen.

There was no change in the theory that someone, most probably Prefontaine and/or Bedford, had to force the pace to spoil the kick of the last-lap speed merchants. But Bedford now was a questionable quality. And when Pre decided not to push the first two-thirds of the race, it almost turned into a farce. No one, absolutely no one, wanted to be caught ahead for very long.

Running at a slower rate than in the 10,000 final, the tightly bunched, jostling, position-shifting pack hit the first three kilometer posts in 2:46.3, 2:46.3 and 2:47.6. It took a ridiculous 8:56.4 to reach 2M. Something had to happen, the 13-man field (Haro failed to start after aggravating an old muscle pull) had to move before long. But who? And when?

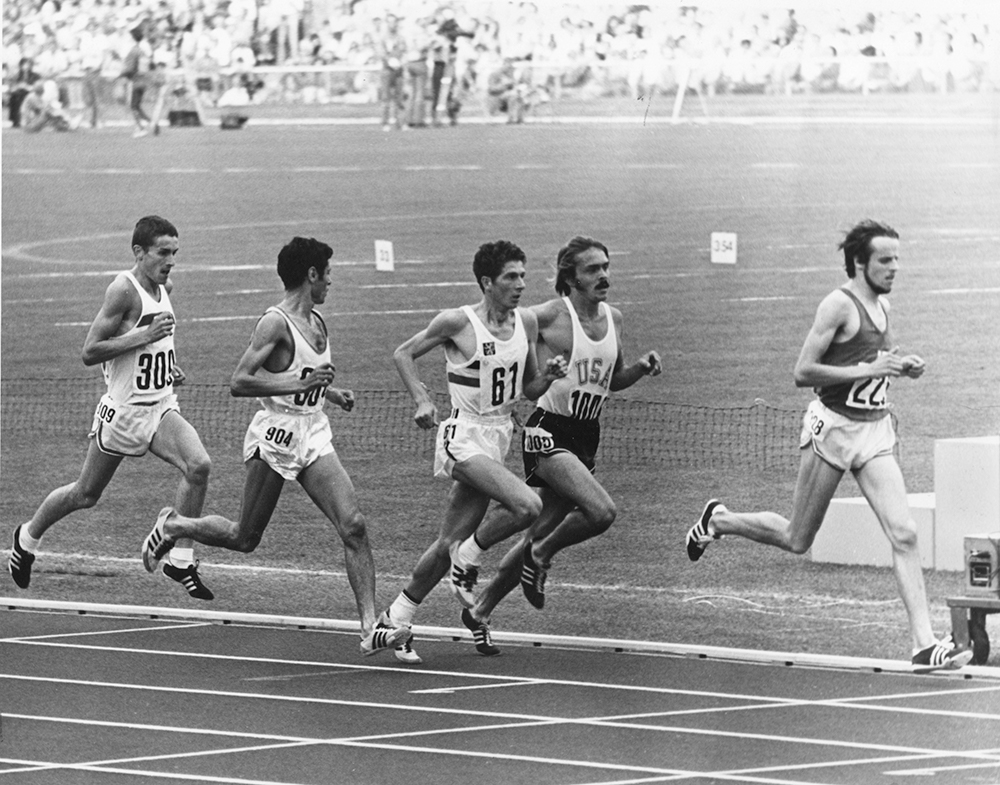

The who was Prefontaine and the when was with 4 laps to go. There was no breakaway attempt. But the pace picked up, the bunch stretched out some, and the race was on. The preceding 4 circuits had taken from 66 to 68.5. Pre gave them a 62.5. Not sensational, but an indication of things to come. He was stringing them out. Then he raised the ante to 61.2 and not everyone had the chips to match. Viren was there, slightly in the lead in fact with 800 to go, and so were Puttemans, Gammoudi and Stewart. There was a significant 8m gap to Norpoth and Eisenberg. Bedford was in bad shape and the others were also out of it with Väätäinen far back and fading.

Full of run and determination, Pre moved back into the lead as they completed the next-to-last backstretch. But Viren, unruffled and dangerous, was alongside and Puttemans and Gammoudi, kickers both, were side by side with only a little space to Stewart, still another finisher.

The tension was approaching a climax as the 5-man race headed toward the bell. Just before it clanged, Pre pushed a little harder and they spread it out a bit just prior to the end of a 60.3 lap. But Viren and Gammoudi, accelerating quickly and easily, responded nicely and it was a threesome at the bell. They had covered the last 1200 in 3:04.0 but the hard running was just beginning.

Viren led into the final backstraight just as Pre launched an all-out sprint. Or at least he wanted to, but Gammoudi moved at the same time, cutting off Pre momentarily as the Tunisian veteran took the lead. Pre got back his momentum, got up alongside Viren and was within a foot of the lead with 210 to go. But he dropped off into 3rd around the curve, gathering for the last, desperate drive.

Viren was there first, however, and there was no stopping him. Moving quickly with a long, almost loping, non-sprinting stride, Lasse wrapped it up. There was no doubt as he steadily pulled away. Nor was 2nd an issue as Gammoudi just as steadily moved away from Pre. The latter had his bronze though—until Stewart, closing with a great but belated rush, caught the staggering Pre with 15m to go. The Englishman also closed on Gammoudi, giving every indication he could have been second had he started sooner. Left behind in the last 300, Puttemans was a safe 5th and Norpoth an unchallenged 6th.

Viren’s last lap was 55.8, and he looked capable of faster. The final 800 was 1:56.1, the last 3 laps 2:57.3, the final 1500m 3:44.7, the last 4 laps 3:59.8 and the final mile 4:01.2. The final kilometer, after a fourth in 2:39.2, was a hyper-fast 2:26.5, just 10.3 seconds over the World Record. And the last 2000m took only 5:06.2, exactly 10 seconds slower than the world mark! It was indeed some running even though the styles of the runners were such, and the race so tight, that it didn’t look that fast.

So full of run that he took one of the quickest of victory laps, Viren said later the race was run as he wanted. “I had the intention of picking up the pace at 3000m. But it was quite difficult as so many runners were ahead of me. So I stayed back and awaited my chance. With 500 to go I found only three men in front of me and that’s when I gave it everything I had and relied on my sprinting force.” /Bert Nelson/

September 1972: Prefontaine Already Viewing Future

Bloody (he was spiked on the left shin early in the going) but unbowed (“I know I’ll be a much stronger and tougher individual next time”), Steve Prefontaine looked back on his Olympic experience.

Why didn’t he go sooner? “I figured if I can’t win in the last 5 laps I’m not going to be the guinea pig the whole way.”

What happened on the last lap? “In the last 300y I got cut off twice. With 300 to go, Gammoudi stepped right in front of me just as I tried to go. I tried it one last time coming off the last corner and the same thing happened. It was all over for me then.”

Lessons learned? “From now on I’m going to be a dirty son of a bitch. I’m going to foul a lot of people. I’ll probably get thrown out of a few races. But it’s time we Americans learned to run like the Europeans.”

Was his training really going so well he couldn’t believe it? “That’s very true until the last week. The Israeli tragedy affected me very much emotionally. I almost didn’t want to compete.”

Why didn’t he win as planned? “The pace wasn’t fast enough. If it had been 8:40 I would have had gold or silver. It would have put crap in their legs. It was set up for Gammoudi and Viren.”

What now? “If I can keep my interest, and find a job that will allow me to train, and there is some progress in the Olympic organization I’ll most likely try in the ’76 Games. I plan on my 6–8 seconds improvement each year.”

How about your fans? “If anything will keep me running, it’s the fantastic response. Complete strangers write wishing me well. The local people are so great, I would have to move away from Oregon. I couldn’t retire here.” /Bert Nelson/

Previously in the Pre Chronicles…

Part 2: The Frosh Year At Oregon

Part 3: The Soph Year At Oregon

Part 4: The Junior Year At Oregon, XC & Indoors

Part 5: “What I’d Like To Do,” by Kenny Moore

Part 6: The Junior Year At Oregon, Outdoors