SINCE MARCH OF 2022 Mike Marsh has guided the U.S. men’s relay program, working in tandem with Women’s Coach Mechelle Lewis Freeman. Both bring experience as medalist members of champion baton squads to the task.

Both 4×1 teams won World Champs gold at Budapest ’23 — a follow-on gold at Oregon22 for the women.

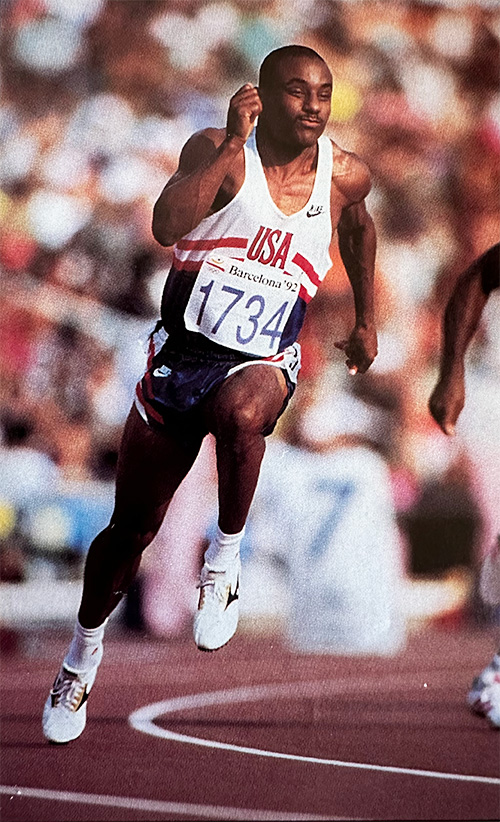

The Olympic 200 winner at the ’92 Games, Marsh’s 19.73 semi in Barcelona was an Olympic Record, American Record and the low-altitude WR at the time. Marsh, everpresent on speedy UCLA and Santa Monica TC relay units of his era, led off the victorious WR-setting USA 4×1 team in Barcelona. A year earlier he collected World Champs gold for his anchor performance on Team USA in the heats (in 37.75, a WC record and to that date the fastest-ever non-final). A relay silver medalist at Atlanta ’96, he has multi-faceted experience with the event.

While coaching at the WIC in Glasgow, Marsh took time out for a phone talk on Team USA relay protocols, philosophy and plans — quadrennially a fraught topic in the press and social media— as the Paris Games roll into view. Transparency in the effort, he asserts, is vitally important to the promotion of success.

Marsh: The goal is to engage and re-engage in a continual conversation loop with the coaches and athletes. The conversations are often complex, but the silver lining is that learning and understanding are improved each time we engage, whether we communicate voluntarily or in response to a conflict that needs resolution. My responsibility is to listen and respond to what is said, independent of how the message is delivered. Specifically, I know some of the deepest and richest learning can come from your critics.

T&FN: Both the men’s and women’s 4×1 squads struck gold last summer in Budapest. While the women also won at Oregon22, the men’s victory was the first at a major championships since the ’19 Worlds. Have you established some systemic improvements that will aid the Paris Olympic team?

Marsh: We’ve done considerable work to address the weaknesses in our system, such as the high turnover of personnel and extremely limited practice opportunities. Coach Freeman and I have been clear about the importance of the information we gather at practices and camps and how that information flows into decision-making, especially for the 4×1. We have objective information, for example, on how fast world-class athletes can move through the exchange zone, and we will be able to use this and other information to evaluate our performances this summer and beyond.

Coach Freeman and I have and will continue to improve our ability to identify and respond to common relay errors. We’ve seen some success in the past couple of years, even though that success is intertwined with several unforced errors. As we analyze those errors, we have noticed some recurring patterns, which we view as opportunities.

T&FN: What plans do you have for the spring relay season?

Marsh: We have several preseason competitions this year, allowing us to look at several athletes. We’ll go to meets like Texas Relays and Florida Relays and assemble some capable teams. We’ll follow on with the World Relays in The Bahamas at the beginning of May. That’ll be another opportunity to sharpen our skills.

The hope is that over the coming months, we will touch as many people who will ultimately make the team as possible so we have some familiarity that we can build on later this season and from year to year. Of course, with the U.S. system, it’s very likely we’ll have someone new, and we’ll have to work them in. But hopefully, over time, when we continue to touch the top sprinters, we’ll be able to start somewhere significantly ahead of ground zero.

T&FN: How will the World Relays squad be selected?

Marsh: The simple way to look at it is we’re going to use some data from 2023 — we’ll automatically, of course, look at people who were in the pool last year — and the additional data that we get from early 2024, put some people together, and take the best team down there that we can.

Since it is an Olympic year and training days are critical, we will have to get clarification on who is interested in participating, which will significantly impact the process. Additionally, we would like to consider a competitive opportunity before the World Relays to increase the odds of improving the outcome.

T&FN: As an athlete you experienced relay highs and lows firsthand. Gold at the ’91 Worlds and ’92 Olympics, silver at Atlanta ’96, and on the downside you were set to anchor in your ’93 World Champs heat but the baton never made it to you.

Amalgamating that now with the perspective of two World Championships in the men’s relay coach role, why has it been a challenge for the deepest sprint nation on earth to win consistently over the last 40 years?

Marsh: There was increasing international competition at least from the first World Championships in 1983 forward. The margins of victory, as well as the general dominance of the U.S. in the sprints, started to be challenged more and more. Our selection system was not designed with the relays in mind because we have obvious structural deficits in our ability to prepare and practice for global championships. The combination of increased international competition and a system not specifically designed for relay competitiveness made the U.S. more vulnerable.

In the ’90s and early 2000s, we had some forces that could help us compensate for our vulnerabilities. We had a few powerful running clubs, Santa Monica Track Club was one, with centralized management and coaching that incorporated relay skills into their training programs. Since then, management and coaching have been decoupled and decentralized, making the coordination required for high-level relay development much more difficult.

There are undoubtedly additional explanations and factors because the question is complex and challenging. We can expect to solve problems faster when we invest the effort to be more precise in identifying the root causes. I have a few mentors I’ve asked to challenge me and my thought process aggressively. When we stop trying to solve problems in isolation, we will be better, and the small price we pay is to give others credit.

Our international competition has responded to the depth of our sprint talent by investing considerable effort in their zone competitiveness. We can expect them to watch, analyze, exploit, and attack every externally visible weakness. Some teams have superb leadership, and underestimating their competitive resolve would be a mistake. Despite the threats, real competitors have fun handling them.

Speed is necessary but insufficient in the 4×1 because the event is not solely a speed event. It is a unique mix of speed, coordination, timing, and synchronization.

T&FN: You’re correct. Armchair quarterbacks of the oval often question relay selections, substitutions, orders, all of these. Any thoughts on that?

Marsh: This is where your accumulated skill in managing your attitude will be sorely tested. Criticism is a remarkable act of friendship independent of the critic’s intent. I prefer to be saved and developed by criticism rather than destroyed by praise.

When I began to mature as a sprinter, I asked Coach Tellez to limit his praise, not that it came that often, but because I didn’t need that as much as in the beginning. I needed the critical voice. The fortunate thing about being a Relay Coach is that I don’t have to ask for criticism; it just comes free of charge. Independent of how criticism is packaged, it has value, so the challenge is to hear what is said as opposed to how it is said. I always learn from criticism, and as I said before, I open myself up to a few mentors who are dedicated to telling me the truth as a primary objective.

T&FN: Sure. As you and the athletes work through this spring, will you be doing a lot of video analysis? You mentioned being data driven, and I’m curious how that works today with so many technological tools available.

Marsh: Right. We regularly measure movements in and through the relay zones and analyze video to verify the accuracy of our intuition.

We spend the most time analyzing mistakes, especially unforced errors, and think through ways to prevent recurrences. There is considerable disappointment when things don’t go as planned, but our goal is to never waste a mistake by not learning from it.

T&FN: Are you in effect taking notes on individual athletes, what they do in the zone, what things that you can coach them on? Are you also analyzing combinations who worked well together and combinations that perhaps worked not quite as efficiently as they could have?

Marsh: We wish we had time to do all those things, but the structural deficits that I mentioned earlier prevent us from doing that kind of analysis between the Trials and the Games. We have the advantage of gaining some of this information across seasons. Our opportunities for analysis are severely limited because we have 3 days (maybe 4) to practice. We consider combinations, but if we do, it is a multi-seasonal consideration but not something we can effectively do in 3–4 days. On the national team, we are forced to attempt to accomplish a goal in 4 days, which many colleges spend an entire season and dozens of sessions on.

We’re looking at baton mechanics, as well. These things are relatively simple, but we look at who does it well in practice, which is a closed, safe environment. We can compare that also to what happens in competition, more of an open environment where you have more anxiety and other factors that you don’t have to deal with in practice. We’re taking some time to look at the delta in the performance between the two to figure out how we can address that and, most importantly, how we can simulate competitive pressures in our training.

Because it’s essential to prepare for the actual situation you will encounter.

T&FN: There’s more diversity of relay experience among top sprinters than in your era. Some skip college, some have the typical four years of collegiate experience — and I suppose could get used to one way of doing things. Others turn pro early. Does all that present challenges for National Teams?

Marsh: We have hundreds of college programs nationwide, and the variance in relay strategy is wide. As you mentioned, some skip college. We’ve experienced the discomfort that athletes feel when they are exposed to our system for the first time. However, we need a consistent U.S. system so that the athletes and coaches have something tangible they can expect and prepare for.

But if we rewind a little bit, I would reiterate that it’s not nearly as important as the structural deficits that we have in our system that we talked about. The experience of the athletes is a factor that is less significant than the others. And as a matter of fact, it’s something that we feel like we can fix even with the time that we’re allotted. It’s a problem, but not as much of a focus or an issue — as opposed to how it may look from the outside. And even though some athletes skip college, we must remember that some freshmen at some major universities do very well with the baton exchange. A lot of high school teams do very well with baton exchanges.

The difference is it’s a little more risky at the elite level, especially on the men’s side, because they’re moving much faster and they are larger. Sometimes it’s a pretty small lane relative to their body size, and you have to pay attention to the details to keep everything under control and ensure that baton pass is smooth. And it’s very doable.

T&FN: How do you manage the “psychology” of the intense pressure on athletes at an Olympics or World Championships? Is there a danger of overthinking the process and having athletes tighten up, in effect?

Twice in the Usain Bolt era I asked Jamaican quartets what they did to prepare for the relay they’d just won. They claimed they only did a few handoffs a day or two before and let their talent take care of the rest. While it’s impossible to know how accurate their accounts were, those teams sure looked relaxed. Maybe Bolt’s supreme confidence was infectious. Do you believe their preparation could have been that minimal?

Marsh: On the first question, I don’t operate alone when dealing with “psychology.” Many athletes prefer to deal with those issues with their personal coaches. I am prepared to assist with some of these issues but within the constraints of respecting the athlete’s relationship with their coach.

And on the second question, the Jamaican system during the era of Bolt didn’t have the turnover of personnel relative to the U.S. Additionally, they had a very compact network of elite personal coaches with some coordinating activity within the whole spectrum from the elite to high school. I could agree that those facts could have a relaxing effect. Similarly, when we had strong track clubs a couple of decades ago that could run 37 seconds in the preseason and then have several of those athletes make national teams, that could also have a relaxing effect on the relay system.

On the flipside, It isn’t easy to rate how accurate that statement about a few handoffs is because it is challenging to have disciplined and accurate analysis from a distance. Additionally, the Jamaicans could rightfully accuse me of having my mouth open without really knowing what I am talking about. Soon after I started with the U.S. relays, more than one of my mentors spoke with me about the dangers of overthinking, so the risk is real.

Another factor is just stability and maintaining the stability of the relay. What I mean by that is — since I ran the relay and those years have become farther and farther away — that we’ve come to a place where we understand the risk of substitutions. We have to take that into account in the way that we make decisions. The other thing that also happens when you analyze the relay is that it comes along infrequently. We have so little data on performance that you’re pretty much sampling these World Championships and Olympic results in light of the structural deficits we’ve already discussed.

T&FN: How do you feel about the buy-in from athletes, coaches, agents, sponsors, broadcasters so far? In days gone by I remember more open tension over who would run anchor. Not so much lately.

Marsh: To be transparent, I’m going to dodge your question intentionally because I run the risk of overestimating the importance of what I think. Securing buy-in is more about listening than anything else. Coach Freeman and I intend to continue communicating openly with all stakeholders in the sport, and though that path is difficult, it is the most likely path to get buy-in. I’m certainly open to listening and contributing; as we advance to more constructive dialogue, we can expect and hope for continued progress.

T&FN: Timely and effective communication with the athletes must be something you think about as coaches.

Marsh: Yes, we are doing our best to improve communication within the team. As an athlete, I remember how important it was to know what was happening with the relay. There are different ways to communicate effectively. Sometimes, we can’t make a decision right away, but we can explain why and say something like “I’m not deciding today” and provide a valid reason for delaying the decision. This can be in the best interest of the team, as there are often good reasons to postpone a decision.

I think the more we communicate with the athletes, the more they understand. We go back to taking a team perspective. I think that could remove some of the suspicion: “The relay coaches aren’t hiding anything from us, but there’s actually more information that they need to collect as a couple of important things transpire in the next few hours or the next few days that will have huge effects upon the decision.”

Sometimes, you want to communicate those things very carefully so that people understand that there are very good reasons to wait — especially when there’s no cost to waiting. That’s just a basic decision-making principle. When you have to make a really big decision, what’s the optimal point in time to make the decision? So I think it’s our responsibility as relay coaches to communicate that to individual coaches and the athletes in a way that’s palatable. That is incredibly difficult, especially in a high-pressure situation. But that’s our job and something that we think about.

T&FN: Do you have relay camps or practices planned for the period between the Trials and the Games?

Marsh: We’re in the final stages of organizing a camp and looking for potential opportunities to compete. So, we’ll look to some of the international meets as possibilities. This can be challenging, but we definitely do our best to make those happen because we understand how valuable they are in terms of preparation.

We’ll gather a bunch of data, some experience, and just a lot of information about the athletes. We’ll use as much of that as we can to build upon the plans that we’ll create once we finish the Trials and figure out how to assemble the best team from that standpoint.

We will add a couple of things between the Trials and the Olympic Games to get appropriate attention and practice for everyone. We work the best we can with the system that we have. And to repeat, we have a great system, but from a relay standpoint, it’s not the ideal system to compete against other countries. So I don’t see that changing. Sometimes you have to figure out how to solve a problem with constraints that you can’t do anything about.

T&FN: Once competition at the Games has started, you’ll have some athletes who will have run the 100 and maybe they’re not running the 200. Will you organize relay practices with those people?

Marsh: We absolutely will work, but part of the calculus — and it’s a huge part of the calculus — is who’s available? It’s a very simple question and when you get down to the onsite interactions, with the athletes it’s a huge factor because many of the athletes will not be available. We will have a couple of picks that may be relay only, but depending on the combinations, that dictates the extent of the work you can do during the Games.

It’s variable. It’s a kind of flow based on what happens in the 100. We have a few days after that to do a little bit of practice, and it becomes very fluid at that point. Then we have to sit down every day to figure out, “OK, how have things changed, and what are the implications for our plans?” It’s a complicated process, but it’s not rocket science. It can be done.

T&FN: It wouldn’t be appropriate to ask you about specific athletes. As you say, the relay is a team and its membership is to be determined. But how do you feel about the “spirit” among recent and potential relay pool members based on the World Championships the past two seasons?

Marsh: When trying to establish relationships with several people, the variance in the quality and spirit can be significant. Some relationships are relatively solid, and some could be helped with a conversation. I feel good about the possibilities of improving existing relationships and constructing new ones. I will travel in the next few weeks and get a chance to work with athletes. Not only on the track but also to get together, sit down, and talk a little bit. We may have a conversation. We may also delve into some other things that athletes want to know. We’re trying to inject a lot of information into the relay system so that everyone involved in it understands as much as possible before we get down into moments where we have to execute a very fast relay.

We don’t want to jam too many responsibilities into a very short period. So Mechelle and I have taken the time to develop relationships as best we can before we get to the Trials to increase the chances that the people who come out of the Trials and onto the team already have a base of knowledge about what to expect from the relay program. That’s an ongoing process that can always be improved and we can always measure. We expect to do that.