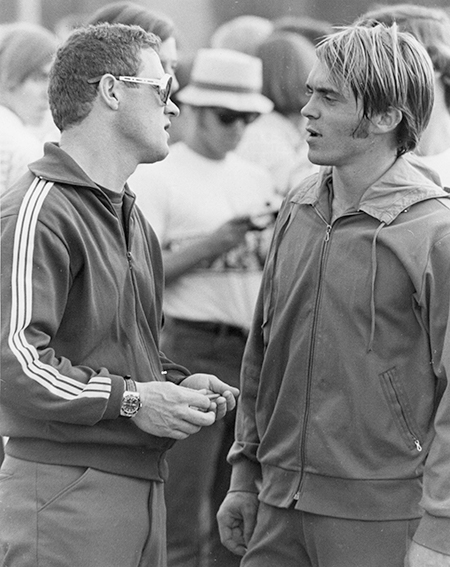

HERE, IN THE FIFTH of a long multi-part series in which we have been reporting the career of Steve Prefontaine in our pages—using the same photographs we ran at the time—we take a break from news coverage. As the ’72 indoor season segued to outdoors in Pre’s junior year at Oregon, noted track writer (and Olympian) Kenny Moore crafted one of the best pieces we have ever published. From the II March 1972 edition:

February’s icy rain slides off dark, looming firs, slickens the flat leaves of dormant rhododendrons and works its way through Steve Prefontaine’s hooded green sweatshirt. He is running 5M with a friend through Eugene’s dim, dripping Hendricks Park. The companion, an Olympian, feels his fingertips crinkling in the wet, feels a rash beginning in his armpits. He longs to be in a sauna or by a fire.

Prefontaine speaks from the depths of his hood, his voice unnaturally cheerful in the hollow forest. “What I’d like to do,” he says, “is run a 6M in about 27:00 in April and about a 3:54 or 3:55 mile in May and then just let those Europeans wonder what I can do in between.”

His friend, hamstrings tightening from the cold, is startled. He seldom thinks of racing when he jogs through the park in winter.

“I’m training to be with the leaders at 2M in 8:25 or so,” continues Prefontaine, “and then picking it up to about 4:05 for the last mile.” As he imagines that race, his pace quickens.

“8:25?”

“It could happen. Guys like [Dave] Bedford, [Jean] Wadoux, even [Harald] Norpoth know they can’t outsprint [Juha] Väätäinen if they don’t hurt him early. I sure hope they do. I want a race where it comes down to who’s toughest, who can push himself the farthest into that kind of exhaustion where running is unnatural, where you have to whip yourself to go on.”

Long before the two runners have curled out of the brooding woods and slopped through the rushing streets to the Oregon campus, Prefontaine has convinced his listener, as he has so many others, of his conviction that for him literally nothing is impossible.

To understand Prefontaine, it is necessary to know something about Coos Bay, Oregon. The town and the man find themselves similarly described: blunt, energetic, tough, aggressive. Coos Bay is a mill town, a fishing town, a deepwater port. Longshoremen, fishermen and loggers are not given to quiet introspection. Coos Bay endures its difficult, elemental life in the woods, on the boats and docks, with a vociferous pride. The working men insist on a hardness in their society. Youth must be initiated, must measure up.

“You don’t have many ways to jump,” says Prefontaine. “You can be an athlete. Athletes are very, very big in Coos Bay. You can study, try to be an intellectual, but there aren’t many of those. Or you can go drag the gut in your lowered Chevy with a switchblade in your pocket.”

In the eighth grade Prefontaine had to jump. “I weighed 90lb so football was suicide. I had tried basketball and I wasn’t any good. It looked like I was headed for the streets. Track was a last resort.”

He found he could run some in a basic-conditioning class. “It was strange at first. Really having a chance to win. I never trained, oh, maybe a little high jumping during the week, but I won some races. It was the Coos Bay hard-guy approach, I’m sure, that kept me going.”

In his freshman year at Marshfield High School, he met Walt McClure. “Coach McClure worked us. Cross country my first year was the first time I ever trained. I couldn’t believe that just running could make you so sore. But after the stiffness went away I acquired a taste for it. Running hard and wet in the woods or on the beach, fighting the wind, I got to love that. I started to feel the challenge. I started to get ideas.”

He started to run like hell. After 4:12 and 9:01 as a junior, Prefontaine and McClure laid out a year-long program directed at one race, a 2M in April at Corvallis. Pre was to break the high school 2M record of 8:48.0 held by Rick Riley.

“Walt prodded me with that in workouts,” says Prefontaine. “If my times for a set of intervals weren’t what he thought I could do, he’d tell me I’d never get the record that way and I’d go back out and run harder. We both got pretty stubborn about that record.

“The night before the race I had an incredibly vivid dream. I ran 8:40 in it. It was so real that when I woke up I thought I had done it. I was tired. When I realized it was just a dream, I thought, ‘Hell, I’ve got to run the whole thing again.’”

He did, churning a 4:16 last mile to clock 8:41.6. “That remains my biggest thrill,” he says. “Everything really began with that race. It proved that if I set myself to do something, I could do it. It was like the sun coming up in my mind, you know? I really began to get ideas. And ever since, anything I’ve set my mind to do, I’ve done. Under 4:00 as a freshman when a lot of people said I was too little or too slow? I ran 3:57.4. The AAU Championships last year? Under 13:00 for 3. People have stopped being so negative. And the older I get, the more stubborn I get. I don’t know if that’s good or bad…”

That expression of Pre’s, almost a disclaimer, is tacked on a lot of his self-assessments. “I don’t know if that’s good or bad…” It is his polite way of saying “This is the way I am. You don’t like it, that’s tough shit.”

In 1969, after graduation, Prefontaine ran 4th in the AAU 3M and made the international team. In the Western Hemisphere vs. Europe meet in Stuttgart, his confidence, to employ a watery word for it, took another step up.

“The papers rated me a poor fourth out of four,” he recalls with relish. “I decided before the race I would just hang on until I fell down. [Gerry] Lindgren went out blazing. He did 2:05, 4:14 and 8:41. I stayed with him and Jürgen May until the last two laps. May jumped Lindgren in the last backstretch and then in the curve Gerry came up with a fantastic finish and won going away.

“I was gone those last two laps, just staggering blind, but for a second there, when Lindgren was passing May and the crowd was screaming, I had one clear thought: ‘Next time.’ I was practically unconscious at the finish. I ran 3rd in 13:52.8 and sure that was good for a high school kid, but the main thing was that I knew it was just a matter of time until I could stay with anyone, all the way.”

Prefontaine roomed with Lindgren in Stuttgart. Gerry spent much of his time discussing theology with steeplechaser Bob Price. Prefontaine shopped for switchblades to resell to Coos Bay hoods.

In the fall of 1969, Prefontaine came to the University of Oregon. He had seriously considered Stanford, Princeton and Villanova and had chuckled over a hundred other offers.

“A guy from Southern California called Walt McClure one day and said they’d like to have me down. Walt asked where they were last year. The guy said he hadn’t heard of me last year. Walt said I was the third fastest 2-miler in the country as a junior and that USC ought to pay better attention. Then he hung up.”

Pre came to Oregon because of William J. Bowerman. “I had all these piles of letters from other schools and nothing from Bowerman, although Bill Dellinger had kept in touch. Then I got a handwritten note. I could barely read it. It said if I came to Oregon, he’d make me into the best distance runner ever. That was all I needed to hear.”

The recruiting of Prefontaine has left stronger impressions upon the recruiters than the recruited. Arne Kvalheim accompanied Bill Dellinger on a trip to Coos Bay during Pre’s junior year. “I had just run 8:33.2 for a collegiate 2M record,” remembers Arne. “Pre had just run 9:01. We took a 10M run on the beach. All the way this kid kept asking me, ‘Getting tired? Am I going too fast for you?’”

Prefontaine’s training at Oregon has not included nearly the volume of running urged at some other schools, but Dellinger is on record as believing that an occasional “killer workout” is necessary for a runner to improve. Pre has not averaged 100M per week until this spring, but some of his individual hard days have been impressive.

In the fall of 1972, he cruised a mile in 4:12 and after a 3:00 jog did eleven 440s in 64. Dellinger asked him if he was tired. Pre simply ran his twelfth 440 in 52.0. He has run 13:58 for 3M by alternating 220s of 30 and 40 seconds. In support of his claim to be competent at 6M, he offers an exercise of early March, a 28:20 with 3M splits of 14:50 and 13:30. His last mile was 4:17, his last five laps 5:22.

All of these track sessions are followed by 4–6M of fartlek through Hendricks Park and, back on the track, four 330y cutdowns from 48 to 42 seconds with a 110 jog between each.

Dellinger attempts to explain Prefontaine’s steady improvement: “In the 2½ years he has been here, he has not once been so sick or hurt that he couldn’t run some. He seems to have such a reservoir of adaptive energy that his running doesn’t weaken his resistance to disease. He also has some sense about not overdoing things.”

Prefontaine says, “I have to have a temperature before I will go to bed with a cold. If I’m feeling down for some reason, I’ll skip a hard workout and just jog all bundled up, for a couple of miles. But when I am recovered I will do that workout harder. I guess the last time I missed more than two days in a row was in 1966.

“I fell down a flight of stairs my first year at Oregon and twisted my ankle. I couldn’t run on the track for two weeks, but the next day I hobbled 2M on the sawdust. I’ve never had a serious injury, just little things. The doctor has told me I have big metatarsal bones; I’ll never have serious foot problems.”

One of those “little things” occurred six days before the 1970 NCAA 3M in Des Moines, when Pre gashed his foot on an exposed metal bolt near his motel swimming pool. “The doctor put in 6 stitches,” he says. “He said I could run on it if it wasn’t too painful, so the next day I went out and tried to jog. It was pretty bad. It felt like my foot was being hammered with a sledge, like it had grown three times as big and turned to mushy hamburger. I soaked it every hour I was awake for 5 days.

“Before the race I put on some ointment that numbed it a little and wrapped it up tight. I won. I shouldn’t have, really, but when I took the lead after a mile the rest of the field let me slow down the pace. I was able to save enough for a 1:58 last 880. When I took the tape off afterward, two stitches came with it.”

When Prefontaine tells this story, the listener senses it is presented as evidence of his apprenticeship, his initiation. He often characterizes himself as a “punk kid” and other runners as “veterans” or “codgers.” (Of Norpoth’s wait-and-kick strategy in the U.S. vs. West Germany dual in 1970 he said: “That was pretty bad, an old man like that letting a kid do all the work.”) He speaks of gaining “maturity.” There can be only one logical goal to this tempering process. Munich.

“If I get there, I won’t be the favorite, and I’ll enjoy that,” he says. “There are big odds against me. Nobody under 25 has ever won the Olympic 5. But if everything goes right, whoever wins will know he has been in one hell of a race. So far, I haven’t been pushed to my limit. I’ve always set the pace. If somebody goes out in steady 63s, I might just hang on.”

Pre turns his relative inexperience to his advantage when he says, “I know pretty well what the best runners can do, what their basic capabilities are. Hell, a lot of them, like Norpoth, [Kip] Keino, [George] Young, are down to their last big chance. But they don’t know what I can do. My progression puts me in the 13:20s this year. But what if I don’t have to set the pace?”

As he thinks of Munich, he inevitably returns to how the 5000 will be run. “I can sprint. If I’d had to, I’m sure I could have come up with a 54 on the last lap of the AAU 3M. But I’d rather run out of gas in Munich than get burned by a kicker. I could lose and live with the knowledge that I’d given 120%, given it all, if I’d been beaten by a guy who came up with 130%. But to lose because I’d let it go to the last lap… I’d always wonder whether I might have broken away…” The thought is clearly intolerable.

For all his singlemindedness in racing, Prefontaine is not a slave to running, or to anything else. He is majoring in Broadcast Communication. His advisor has been impressed with his academic progress in the last year, saying, “He is very capable. In class he presents a challenge that we like to get from students. It is as if he is saying, ‘If I am going to put in this time and effort, you had better make it worth my while.’ I think he has a good chance of making a contribution to the theory and criticism of communications.”

Certainly to the criticism. Prefontaine’s remarks on southern California’s weather, attitude toward track & field, and its sportswriters have reverberated up and down the coast since he was a freshman.

“I used to hate the press even more than I do now,” he says with a smile which removes some of the sting from the words. “In high school, photographers would be prowling around the infield during meets and they’d ask, ‘You Prefontaine?’ I’d say no.”

Last spring, Pre was quoted in the LA papers as criticizing UCLA coach Jim Bush for forcing his athletes to double. “That was a perfect example of the kind of thing those guys do,” he snorts.

“What happened was that I had won the mile in our dual meet with 3:59 and a reporter from the Christian Science Monitor asked me why I didn’t double. We were having a good interview, really deep, way beyond the level of most big city nitwit sportswriters. I told him that doubling week after week could hurt you inside, could make you not quite so eager to compete hard. I told him that when I did double it had to be a joint decision between Bowerman and me, a decision either one of us could veto.

“Well, the rest of the reporters were standing back about 20 feet, trying to pick up scraps of what we were saying. They found criticism where there was none. Jim Bush is a great coach. We get along fine. The press has been really irresponsible in reporting that we don’t.”

Bowerman is succinct on Prefontaine: “He’s a rube. By that I mean he has got that kind of wide-eyed, nothing-is-impossible straightforwardness that is rare these days. You ask a rube a question, you get a straight answer. This guy doesn’t play games with you.”

Concerning his plans for after Munich, Prefontaine says, “I like to run. My personal view, and that of the Oregon system of training, is that I can continue to improve at least until I’m pushing 30. But if I don’t find racing enjoyable, I’ll quit doing it. I’ll probably never quit running just for fun. If the press, the media, bug me like they have one or two others I could mention, forget it. I’ll write a book.

“I find satisfaction in my progress. That’s enough to keep me going. What I’m doing is interesting to enough people—a hell of a lot of them in Coos Bay—that I can feel them backing me. I don’t figure to get bored.”

That backing, at its most tangible, earsplitting peak, may be observed whenever Pre performs on Oregon’s Stevenson Track. His legions applaud every step, including warm-up and victory laps. It is a spectacle which seems the ultimate in non-verbal mass communication.

“Anybody wearing the lemon and green will have something extra going for them here in the Olympic Trials,” he says. “The crowd will give them a reserve of power. It’s a strange sensation. If you’re down to a ragged nothing, the crowd can carry you. You can feel their need. It’s in your head. And you have to give it to them. You’re almost driven.”

It may not be transitory, the crowd’s effect upon Prefontaine. It may stay inside him, to be measured out a little at a time on rainy winter days. It most certainly will take him to Munich. It may take him a good deal farther.

Previously in the Pre Chronicles…

Part 2: The Frosh Year At Oregon

Part 3: The Soph Year At Oregon

Part 4: The Junior Year At Oregon, XC & Indoors