FOR OUR NOVEMBER 2010 issue, Jon Hendershott interviewed 2008 Olympic 110 hurdles bronze medalist David Oliver, now the director of track & field at his alma mater, Howard. When he spoke with Hendershott, a World Championships gold medal waited 3 seasons in his future. The powerfully built Colorado native remained active as a competitor through 2017 and subsequent to this interview earned 6 more World Rankings spots, including a No. 1 in 2013. “King Oliver” added to his collection of USATF crowns in 2011 and 2015.

With meets to report on during the current pandemic season scarce for the moment, we’ll be rebooting more content from years past. Our full T&FN Interview Archive, with most of the offerings in PDF form, may be found here.

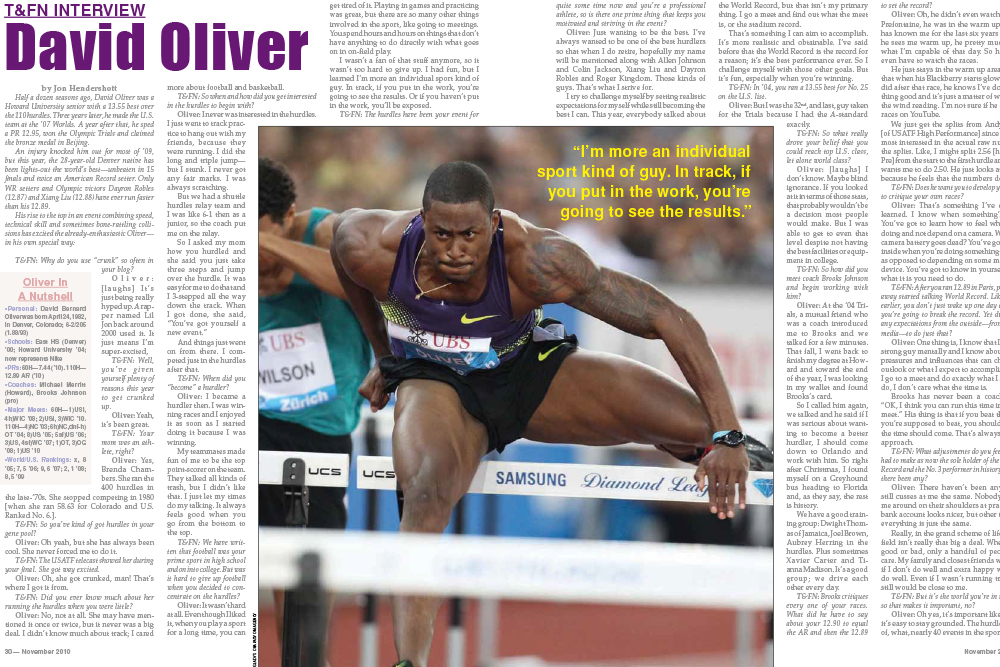

Half a dozen seasons ago, David Oliver was a Howard University senior with a 13.55 best over the 110 hurdles. Three years later, he made the U.S. team at the ’07 Worlds. A year after that, he sped a PR 12.95, won the Olympic Trials and claimed the bronze medal in Beijing.

An injury knocked him out for most of ’09, but this year, the 28-year-old Denver native has been lights-out the world’s best—unbeaten in 15 finals and twice an American Record setter. Only WR setters and Olympic victors Dayron Robles (12.87) and Xiang Liu (12.88) have ever run faster than his 12.89.

His rise to the top in an event combining speed, technical skill and sometimes bone-rattling collisions has excited the already-enthusiastic Oliver—in his own special way: (Continued below)

T&FN: Why do you use “crunk” so often in your blog?

Oliver: [laughs] It’s just being really hyped up. A rapper named Lil Jon back around 2000 used it. It just means I’m super-excited,

T&FN: Well, you’ve given yourself plenty of reasons this year to get crunked up.

Oliver: Yeah, it’s been great.

T&FN: Your mom was an athlete, right?

Oliver: Yes, Brenda Chambers. She ran the 400 hurdles in the late-’70s. She stopped competing in 1980 [when she ran 58.63 for Colorado and U.S. Ranked No. 6.].

T&FN: So you’ve kind of got hurdles in your gene pool?

Oliver: Oh yeah, but she has always been cool. She never forced me to do it.

T&FN: The USATF telecast showed her during your final. She got way excited.

Oliver: Oh, she got crunked, man! That’s where I got it from.

T&FN: Did you ever know much about her running the hurdles when you were little?

Oliver: No, not at all. She may have mentioned it once or twice, but it never was a big deal. I didn’t know much about track; I cared more about football and basketball.

T&FN: So when and how did you get interested in the hurdles to begin with?

Oliver: I never was interested in the hurdles. I just went to track practice to hang out with my friends, because they were running. I did the long and triple jump—but I stunk. I never got any fair marks. I was always scratching.

But we had a shuttle hurdles relay team and I was like 6-1 then as a junior, so the coach put me on the relay.

So I asked my mom how you hurdled and she said you just take three steps and jump over the hurdle. It was easy for me to do that and I 3-stepped all the way down the track. When I got done, she said, “You’ve got yourself a new event.”

And things just went on from there. I competed just in the hurdles after that.

T&FN: When did you “become” a hurdler?

Oliver: I became a hurdler then. I was winning races and I enjoyed it as soon as I started doing it because I was winning.

My teammates made fun of me to be the top point-scorer on the team. They talked all kinds of trash, but I didn’t like that. I just let my times do my talking. It always feels good when you go from the bottom to the top.

T&FN: We have written that football was your prime sport in high school and on into college. But was it hard to give up football when you decided to concentrate on the hurdles?

Oliver: It wasn’t hard at all. Even though I liked it, when you play a sport for a long time, you can get tired of it. Playing in games and practicing was great, but there are so many other things involved in the sport, like going to meetings. You spend hours and hours on things that don’t have anything to do directly with what goes on in on-field play.

I wasn’t a fan of that stuff anymore, so it wasn’t too hard to give up. I had fun, but I learned I’m more an individual sport kind of guy. In track, if you put in the work, you’re going to see the results. Or if you haven’t put in the work, you’ll be exposed.

T&FN: The hurdles have been your event for quite some time now and you’re a professional athlete, so is there one prime thing that keeps you motivated and striving in the event?

Oliver: Just wanting to be the best. I’ve always wanted to be one of the best hurdlers so that when I do retire, hopefully my name will be mentioned along with Allen Johnson and Colin Jackson, Xiang Liu and Dayron Robles and Roger Kingdom. Those kinds of guys. That’s what I strive for.

I try to challenge myself by setting realistic expectations for myself while still becoming the best I can. This year, everybody talked about the World Record, but that isn’t my primary thing. I go a meet and find out what the meet is, or the stadium record.

That’s something I can aim to accomplish. It’s more realistic and obtainable. I’ve said before that the World Record is the record for a reason; it’s the best performance ever. So I challenge myself with those other goals. But it’s fun, especially when you’re winning.

T&FN: In ’04, you ran a 13.55 best for No. 25 on the U.S. list.

Oliver: But I was the 32nd, and last, guy taken for the Trials because I had the A-standard exactly.

T&FN: So what really drove your belief that you could reach top U.S. class, let alone world class?

Oliver: [laughs] I don’t know. Maybe blind ignorance. If you looked at it in terms of those stats, that probably wouldn’t be a decision most people would make. But I was able to get to even that level despite not having the best facilities or equipment in college.

T&FN: So how did you meet coach Brooks Johnson and begin working with him?

Oliver: At the ’04 Trials, a mutual friend who was a coach introduced me to Brooks and we talked for a few minutes. That fall, I went back to finish my degree at Howard and toward the end of the year, I was looking in my wallet and found Brooks’s card.

So I called him again, we talked and he said if I was serious about wanting to become a better hurdler, I should come down to Orlando and work with him. So right after Christmas, I found myself on a Greyhound bus heading to Florida and, as they say, the rest is history.

We have a good training group: Dwight Thomas of Jamaica, Joel Brown, Aubrey Herring in the hurdles. Plus sometimes Xavier Carter and Tianna Madison. It’s a good group; we drive each other every day.

T&FN: Brooks critiques every one of your races. What did he have to say about your 12.90 to equal the AR and then the 12.89 to set the record?

Oliver: Oh, he didn’t even watch them. At Prefontaine, he was in the warm up area. He has known me for the last six years and after he sees me warm up, he pretty much knows what I’m capable of that day. So he doesn’t even have to watch the races.

He just stays in the warm up area. He says that when his Blackberry starts glowing like it did after that race, he knows I’ve done something good and it’s just a matter of waiting for the wind reading. I’m not sure if he even sees races on YouTube.

We just get the splits from Andy Ferrara [of USATF High Performance] since Brooks is most interested in the actual raw numbers of the splits. Like, I might split 2.56 [his split at Pre] from the start to the first hurdle and Brooks wants me to do 2.50. He just looks at the data because he feels that the numbers don’t lie. (Continued below)

T&FN: Does he want you to develop your ability to critique your own races?

Oliver: That’s something I’ve definitely learned. I know when something’s wrong. You’ve got to learn how to feel what you’re doing and not depend on a camera. What if the camera battery goes dead? You’ve got to know inside when you’re doing something correctly, as opposed to depending on some mechanical device. You’ve got to know in yourself exactly what it is you need to do.

T&FN: After you ran 12.89 in Paris, people right away started talking World Record. Like you said earlier, you don’t just wake up one day and decide you’re going to break the record. Yet did you feel any expectations from the outside—from fans, the media—to do just that?

Oliver: One thing is, I know that I’m a very strong guy mentally and I know about outside pressures and influences that can change my outlook or what I expect to accomplish. When I go to a meet and do exactly what I set out to do, I don’t care what the time is.

Brooks has never been a coach to say, “OK, I think you can run this time in the next meet.” His thing is that if you beat the people you’re supposed to beat, you should win and the time should come. That’s always been my approach.

T&FN: What adjustments do you feel you have had to make as now the sole holder of the American Record and the No. 3 performer in history—or have there been any?

Oliver: There haven’t been any. Brooks still cusses at me the same. Nobody parades me around on their shoulders at practice. The bank account looks nicer, but other than that, everything is just the same.

Really, in the grand scheme of life, track & field isn’t really that big a deal. Whether I do good or bad, only a handful of people truly care. My family and closest friends will be sad if I don’t do well and extra happy when I do do well. Even if I wasn’t running track, they still would be close to me.

T&FN: But it’s the world you’re in right now, so that makes it important, no?

Oliver: Oh yes, it’s important like that. But it’s easy to stay grounded. The hurdles are one of, what, nearly 40 events in the sport. I’m just one great athlete but there are a lot of other great athletes in the other events. So I don’t expect to get different treatment. I just want to go out there and be the best David Oliver that I can possibly be. Hopefully, at the end of the day, that’s good enough.

I think that’s one thing that all athletes have to realize: that they aren’t bigger than the sport. When I retire, the sport will go on. But while I’m here, I’ll try to do the best I possibly can, for myself and the sport.

T&FN: Was one race in 2010 the most satisfying for you?

Oliver: I think the most satisfying race was back at World Indoors when I got the bronze medal. Coming off that [calf] injury from ’09—which I did twice; I tweaked it again in Brussels—I was so unsure of myself. Brooks wouldn’t let me start hurdling until I went to my first indoor meet last winter in Glasgow [at the end of January].

I hadn’t done much hurdle work, but later I got 2nd at Nationals and then the Worlds were similar: Robles and Terrence [Trammell] were the top guys, but there were four or five who could try for that third medal. So to get that bronze, and run a personal best [7.44] at the same time, showed me that if I stayed healthy I could have a good outdoor season. (Continued below)

The indoor Worlds gave me the confidence that I was back, that I could run a personal best and it just went on from there. That was the race that really gave me the momentum for the whole season.

T&FN: Of course, Robles was out due to injury most of this outdoor season. You beat him the one time you met—in mid-May in Daegu, of all places, considering next year. But did you miss not having him in all the big races during this season?

Oliver: Personally, I didn’t miss him because I’m just going to go over those 10 hurdles in my lane, regardless of who is in the race. But I did miss him from the standpoint that it would have been really, really good for the event if he had been racing.

He would have been right down there where I was and we would have had so many great neck-and-neck races. So from a performance aspect, my times definitely would have been better and his would have been, too.

It would have been great for the sport, with the head-to-head rivalry. Coming off that 12.90 at Prefontaine, then we would have met up in Paris and a few more after that. So it would have been extremely good.

I think he has helped me with my focus. When he stopped running in ’08, I was running 13.20s. I was too busy worrying about the competition, rather than competing against the clock—which is the truth of competition.

But this year, I’ve run… I don’t want to call them time trials, but I know that after about the second hurdle, I’m going to pretty much be out there on my own the rest of the race. This year, I’ve matured mentally and been able to get the job done, no matter what. That’s a stark contrast from how it was in ’08.

T&FN: So if you are leading by the second hurdle, does the motivation become simply to win?

Oliver: Well, winning was the thing in ’08, too, but I wasn’t getting my best performance. Now when I go to a meet, I leave everything I have on the track. You have to do that because you really don’t know when you walk off that track if you’re ever going to get back on it.

That’s something I used to take for granted, but now it’s not something I take for granted. Every time I cross the finish line, I know in myself that there isn’t anything more I could have done in that race.

T&FN: Was one race this season particularly unsatisfying to you?

Oliver: Well, I can’t be unsatisfied when I won every race outdoors. But one that wasn’t satisfying was the semifinal at the USAs. I didn’t have good hurdle technique, so it just wasn’t a very good race.

I made a lot of mistakes and I couldn’t be happy with the performance going into the final. I always want the time to be in the 12s, not the 13s. I always want my times to be the 1-2s, not the 1-3s. ◻︎