TO THE TRUE-BLUE track & field fan in the United States, nothing says spring quite like a relay carnival. Essentially an American invention, relay racing is our country’s major contribution to the sport’s list of events and it’s little wonder that these relay carnivals jump start our hearts for outdoor track each year.

This year, for the first time since the 1890s, the starting guns for our most vibrant relay festivals fell silent. The annual rite of spring was gone, and athletes, coaches, fans and officials all felt the loss at every level: professional, collegiate and high school. Here’s a look at what the experience was like for the Big 4 of these meets, from East to West:

Penn Relays: Doing The Courageous Thing

After 125 years without a cancellation, America’s oldest relay carnival had no choice but to call off this year’s edition. Explains meet director Dave Johnson, “There was no decision to be made. We were going to be told, ‘You can’t do this.’ The first brick to fall out of the wall came 10-12 days earlier when the Jamaican health minister said that nobody would be allowed to fly out for the Penn Relays. Two days later I got a call from Baltimore County letting me know that school kids would not be allowed to bus outside the county.”

The bricks kept falling. Then on March 12, the whole wall collapsed. “At about 3:30 our time I found out that runners on the NCAA track in Albuquerque were told that the meet was called off and they were to pack up and go home. Then at 4:00 we heard that the Ivy League had announced that there would be no spring sports. And at 4:30 we heard that the NCAA had canceled all spring sports.

“The next day we had a meeting and looked at our options. If we only had half the high schools, that would still be 6000 kids. How the heck could you create social distancing for 6000 people in that stadium? For the field events, potentially after each pole vaulter jumps, you’ve got to sanitize the mat again. You have to do the same with the shot and the javelin before you return it. The long and the triple jumps are presumably the only safe events out there.

“Friday we were notified that Penn was shutting down all campus activities until May 12. The optics of having a Penn Relays when the host league is no longer competing and the host school is not in session were not good,” says Johnson with a grim chuckle.

The East Coast scene outdoors revolves around Penn. The tradition of the meet is indelible in the memories of the thousands and thousands of people who have participated over the years. Many of them are fans and coaches now, and Johnson heard from plenty about the cancellation.

“They were equally split,” he says. “Everyone talked about doing the courageous thing; it didn’t matter what side they were on. ‘Do the courageous thing—stand up for the kids to have a meet.’ Or it was, ‘Do the courageous thing, for everybody’s safety, call off the meet.’

“It’s the seniors that I’m upset for. Particularly the high school seniors, because there’s a good many of them who have been working their butts off for 3-4 years to make that relay team, and now they can’t do it. They don’t get that chance to run in front of 30,000-40,000 people. That would have been a lifetime memory.”

Johnson says the Relays organization is open to a late-summer/fall event, but it’s far too soon to say what that might look like. “We don’t really have to make decisions,” he says. “We have to adapt to evolving challenges and come up with contingency plans and revised contingency plans and just keep bouncing backward from that. We’re going to be told all the way down the line what we cannot do. That’s the way that was always going to play out.”

In the fall, any potential track event would have to share the stadium with football, field hockey, soccer. “Maybe you could have an evening track meet but it couldn’t be too big, couldn’t go on too long,” he says. “There are all sorts of ways to cobble something together. There is potential. It’s a chance to put on a different kind of meet. An all-pros meet. A distance carnival. A sprints/hurdles meet. Or just jumps.”

He adds with brutal honesty, “It’s an unknown mess out there. All we can do is be ready to jump at a moment’s notice.”

Drake Relays: “It’s More Than Just A Track Meet”

At least in terms of crowd size, the Drake Relays got off to an inauspicious start in 1910, when reporters noted that the crowd was only about 100 Drake students in addition to officials and athletes, thanks to a blizzard that hit Des Moines that day.

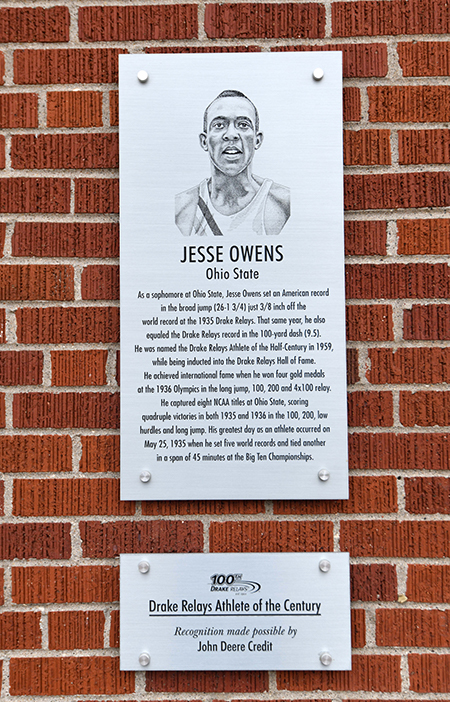

In the years since, the meet has become a staple for track fans and teams in the Midwest, and has drawn big-name performances as well, from Jesse Owens to Michael Johnson. Last year’s meet was highlighted by a riveting vault duel between Sandi Morris and Jenn Suhr, while Ryan Crouser managed a shot win even though, as he put it, “hats were blowing off people’s heads; it was raining sideways.”

This year, during Relays week, “The weather was absolutely gorgeous,” says director Blake Boldon. That weekend he managed a social media blitz that included 23 Instagram interviews with top athletes. “Every one of them asked me what the weather was like. And Ryan Crouser, last year the only meet he didn’t throw over 22m [72-2¼] was the Drake Relays. The only reason was that by the time he finished throwing, it was rainy, windy and in the 30s. When Ryan heard that it was 70, sunny and no wind, he had a very ironic smile.

“Our reputation over the last few years is the weather can be tough. With the weather we had this year, the performances would have been great.”

Yet despite the occasionally challenging weather of the Midwest, over 110 years the Drake Relays had never been postponed or canceled. Boldon says, “The biggest departure from normalcy was in 1944, when all of the medal winners were awarded certificates saying that they could redeem their certificates for medals after the war.” The metal to make the medals was needed for the war effort.

That factoid was made real for Drake organizers last year when 93-year-old Ted Williams, the high school discus runner-up 75 years earlier, dug up his certificate and finally redeemed it for a medal.

Perhaps that perfect 110-year record is part of why the university postponed the meet instead of opting for an outright cancellation. Boldon says, “The weekend prior to our announcement of the postponement, not only did the CDC make recommendations, but also we had a mayoral proclamation that limited events… without a foreseeable end in sight.”

He adds, “There were three days between the time we knew we needed to postpone until the time when we announced, that was because our event is a cornerstone of so many people’s spring on their calendar. It’s more than just a track meet.” Among the many participants and stakeholders for the weekend, he notes “hundreds of bulldog owners competing for the title of Most Beautiful Bulldog.”

Postponement means the organization has stayed in what Boldon calls “a state of active planning. That does not mean we’re in the process of planning for a mass gathering in the short term. We’re also looking at what would make sense for a non-traditional college element, a non-traditional high school element.” Yet no date has been set on a calendar that for the sport worldwide is anything but engraved in stone.

“Economic and political sentiment does not ensure public safety and while we at Drake University are committed to doing all we can to host a track & field event, we’ll remain focused on the safety of the athletes, the safety of the officials and the safety of our community,” says Boldon.

Noting Seb Coe’s statements that this year’s international track season is scheduled to be back in late summer and fall, Boldon says, “College football is going to have to make many hard decisions and develop protocols before we will, if we’re part of that timeline. That is to our advantage in that we are part of a college athletic department that is forced to have these ongoing conversations about when it’s safe to return to campus, return to activities. It helps me understand what our opportunities are in terms of returning to our normal event or some version of the Drake Relays in the fall.”

Texas Relays: “Our Guests Are Its Life Blood”

When Longhorn coach Clyde Littlefield and AD Theo Bellmont founded the Texas Relays in 1925, they aimed for the stars—and got them. That first edition produced big crowds, plenty of publicity, and a World Record high jump by Harold Osborn, who had won Olympic gold the year before.

Publicity was key in the early years, as organizers showed in ’27 when they staged an 89.4M (143.9K) race from San Antonio to the stadium with members of the famed long-distance running Tarahumara tribe of Mexico—it ended in a hard-to-believe tie. The buzz over the race was so big that the Kansas Relays brought in their own Tarahumaras for a run from Kansas City to Topeka.

Yet in ’32, faced with the challenge of the Great Depression, Littlefield opted to cancel that year’s event. Another factor he cited was that he didn’t want to conflict with the staging of the Olympics in Los Angeles.

In ’35, the university brought the Relays back in a dazzling session that left most of the meet records broken. Since then the meet has been a highlight of every spring, attracting crowds of up to 50,000 to see notables ranging from Johnny “Lam” Jones to Louise Ritter to Mondo Duplantis.

This year’s edition, according to director James Barr, was full-speed-ahead—until it wasn’t. “We never said never until we received final guidance from our conference that we couldn’t host spring events. We were preparing for all scenarios.”

That doesn’t mean the decision was an easy one for the people who make the meet happen. “We’re all tremendously missing track & field, and not hosting the 93rd edition of the Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays this March was really emotional for us all,” says Barr.

Thus far, there has been no serious consideration of a fall event. Says Barr, “Next year’s relay schedule has been communicated and is set for March 24-27, 2021.”

He adds, “We can’t wait to embrace the Olympic year again. That pitch remains aligned with celebrating Coach [Edrick] Floréal, our historic program and its history in all regards, while also embracing all participants and stakeholders.

“We take so much pride in running an objective event of integrity and promoting the sport and Relays on campus, locally, statewide, nationally, and worldwide. All of our guests are its life blood and we’ll embrace that!”

Mt. SAC Relays: New Stadium’s Grand Opening Delayed

In 1978 the rains came down on the Mt. SAC Relays. Over what was described as “an unusually rainy winter” for the SoCal venue, some 40 inches of rainfall slowed down construction of the community college’s new track—ironically, its first all-weather oval.

A week before the event was to kick off, a local paper ran the headline, “Mt. SAC relays canceled.”

But not so fast—Don Ruh, the director at the time, held all the events that he could: a high school decathlon, the steeple and 10,000, as well as a marathon. Recalls current director Doug Todd, “Even though we didn’t have the program that we normally had, Don and company considered the shortened schedule an event nonetheless. That was probably the closest we’ve ever come to canceling.”

Mt. San Antonio College had brought the concept of the relay carnival to the West Coast in ’59 with a bang-up debut that saw Oregon’s Bill Dellinger win outstanding track athlete honors after just missing the American Record in the 2M. San José State’s Ray Norton won the 100y in 9.5 and Charley Dumas high jumped 6-9½ (2.07).

Since then the Walnut classic—with more emphasis on individual events than Penn—has been a major highlight of the calendar and has produced more than its share of great performances. The meet records list says it all: a 6910 heptathlon (JJK), dashes of 9.86 (Ato Boldon) and 10.87 (Merlene Ottey), long jumps of 28-5/8.66 (Carl Lewis) and 23-4½/7.12 (Brittney Reese) and on and on

Major reconstruction began in ’16 on Hilmer Lodge Stadium, an $87 million project that rendered the track unusable for four editions. Todd remembers thinking, “Maybe we should just go dark.”

He adds, “I was able to go talk to the president about it and he said, ‘Naw, let’s do it someplace else.’ He was very wise.” The ’16 edition took place in Norwalk, and the next three in Torrance. The Relays maintained their place on the dance cards of many top athletes. “But we never anticipated something like this happening,” says Todd of the current pandemic.

This April’s event was set to be the unveiling of Mt. SAC’s new state-of-the-art track facility. Yes, Hilmer Lodge Stadium is complete, and the grand opening ceremony was set for April 4, ironically beating Eugene’s Hayward Field to the finish line.

(Recall that in June ’17, USATF awarded the ’20 Olympic Trials to Mt. SAC. The following May, citing concerns that the stadium would not be ready in time, USATF took the meet away. Bidding was reopened for the event and Eugene was fast-tracked to be the host once again.)

Todd says that in the end, canceling this year’s Relays was not a difficult decision; in fact, it wasn’t even a choice. “Everybody was sorry that we had to do it, but it really was a no-brainer. The emotional part came the weekend of. We were all texting each other talking to each other, ‘We’d be running the 10,000s now,’ or, ‘The Meet of Champions would just be starting.’”

Todd notes that since everything shut down at about the same time in Southern California, “There’s been no real hue and cry. The few people I have seen were basically just expressing their condolences.”

Now, he says, he and his team are looking at whether they may stage a fall event, and what it might look like. “One of our local assemblymen gave us an update concerning the possibility of returning to activities sooner than we were all thinking. So, if the opportunity presented itself and there was an appetite for it with the administration on campus, we would look for something like that. We have no real date, just a wait-and-see attitude.”

He warns that with the challenges of setting up a safe event with possibly large crowds, “It would be very difficult approaching what we normally do. Plus, with the schools, everybody’s pretty much graduated. There’d be a whole group of people who aren’t part of their institutions anymore.”