HELSINKI, FINLAND—Mary Decker surprised the experts at the IAAF’s first-ever World Championships. T&FN’s WC Preview had tabbed her for 4th in the 1500 and a silver in the 3000. Instead, the former wunderkind, still only 25, parlayed a pair of great homestretch drives into double golds. Here, from the September ’83 issue, are the three pieces we wrote about the inspired running that landed the future Mary Slaney on our cover:

3000: Decker Stuns Soviets In The Stretch

by Bob Hersh

How good is Mary Decker? Until the Helsinki 3000 we could never be sure. In spite of a portfolio of excellent times at distances from 800 through 10,000 meters, she had been untested recently against the Soviets, whose corps of middle distance runners defines world class in these events.

The last time Decker had faced any USSR runner was in Zürich in ’80. The distance then was 1500, and although Decker set an American Record, she was beaten by 50y as Tatyana Kazankina set a World Record that still stands.

It was all the more significant, then, that 2-time Olympic 1500 gold medalist Kazankina turned out to be one of the Soviet entries in the 3000 in Helsinki. Another was Svetlana Ulmasova, the World Record holder. She won the first heat (which eliminated Brenda Webb and Monica Joyce), while Kazankina and Decker virtually dead-heated in the second (which knocked out Maggie Keyes).

The third Soviet entry was 20-year-old Natalya Artyomova, who barely qualified out of the first heat. With apparently better entries at home, Artyomova’s presence gave rise to some speculation as to her intended role. Would she be used as a sacrificial lamb and try to trap Decker into following a suicidal pace? Would she be used as a blocking back? “We are aware of both of those possibilities,” said Dick Brown, Decker’s coach, “and we’re prepared for them.”

As it turned out there was little need for any such preparation. Decker controlled the final from beginning to end without the slightest interference from the Soviets or anyone else. She split 66, 70,71, 71, 71, 70 through the first 6 laps. “We started out a little faster than I had wanted; then it was a little slower,” Mary recalled, “but I wasn’t really concerned. I know I’m strong enough and I had confidence in my kick. Also, I knew that the slower I could run the race and still win, the better off I’d be for the 1500.”

Although Decker’s pace was not fast enough to threaten any records, it did separate the field. After a few laps, the only runners left in close contact with the lead were the two top Soviets, Brigitte Kraus, Wendy Sly and Agnese Possamai.

The order of this group shuffled back and forth some, but Decker remained in front always. This caused some of her fans to wonder if she could bear the psychological burden of setting the pace for the entire course. Not to worry: “Unless someone else is setting a 64-65 pace, or something crazy, it doesn’t bother me at all to be in the lead. I actually find it more relaxing to lead than to follow. I didn’t mind doing it.”

The penultimate lap was a 69. At the bell, the tempo picked up and the race became very exciting. Down the backstretch, the Soviets found themselves boxed, Kazankina inside of Sly right behind Decker, and Ulmasova inside of Possamai and Kraus a few steps back.

As the group came around the final turn, however, room opened up and it could have been anyone’s race. From 5th, Ulmasova swung wide and with the open straightaway in front of her was perfectly positioned to show the strength that had earned her two European Championships. In 2nd, Kazankina was now clear. She closed the gap on Decker and they were practically even with 50m to go.

Decker, having led every step of the race, was apparently about to succumb to the pursuers who had patiently stalked her for 7 laps. But it was an illusion. With amazing ease, she made a magnificent move that drew admiration from even her biggest skeptics. Smoothly slipping into another gait and speeding to the tape, she opened a steadily increasing margin that was more than 10ft at the finish. The winning time was 8:34.62, Decker’s seasonal best.

Kazankina, totally dispirited by this kick, slowed her pursuit when it became obvious she could not win, and thus allowed Kraus to edge her in the closing steps for the silver. At 8:35.11, this was a big PR for the runner-up. Ulmasova, who probably forfeited any chance of winning by not moving a lap earlier, proved not to have the quickness for a homestretch shootout.

The Soviet coaches, not being blind or stupid, will go home and put their 3000-meter runners through more speed training in the next year than they’ve ever done before. Perhaps things will be different in Los Angeles. But for now, we all know how good Mary Decker is. She is simply the best in the world.

3000 Results (August 10)

1. Mary Decker (US) 8:34.62 (x, 2 US)

(halves—4:21.4/4:13.3) (kilos—2:51.0, 2.57.2 [5:48.2], 2:46.5) (finish—28.9, 60.8, 2:10.0, 3:21.6, 4:32.4)

2. Brigitte Kraus (West Germany) 8:35.11

(4.22.2/4:13.0) (2:52.1, 2:57.7 [5:49.8], 2:45.4) (29.2, 61.2, 2:10.3, 3:21.1, 4:32.3)

3. Tatyana Kazankina (Soviet Union) 8:35.13

(4:21.4/4.13.8) (2:51.3, 2:57.9 [5:49.2], 2:46.0) (29.2, 61.3, 2:10.4, 3:21.1, 4:32.8)

4. Svetlana Ulmasova (Soviet Union) 8:35.55

(4:21.6/4:14.0) (2:51.6, 2:57.8 [5:49.4], 2:46.2) (29.4, 61.6, 2:10.7, 3:22.2, 4:32.9)

5. Wendy Sly (Great Britain) 8:37.06

(4:21.6/4:15.5) (2:51.7, 2:57.5 [5:49.2], 2:47.9) (31.0, 63.1, 2:12.3, 3:23.8, 4:34.4)

6. Agnese Possamai (Italy) 8:37.96

(4:21.6/4:16.4) (2:51.7, 2:57.6 [5:49.3], 2:48.7) (32.1, 64.0, 2:13.2, 3:24.6, 4:35.4)

7. Jane Furniss (Great Britain) 8:45.69 (4:23.2/4:22.5); 8. Natalya Artyomova (Soviet Union) 8:47.98 (4:25.9/4:22.1); 9. Aurora Cunha (Portugal) 8:50.20 (4:23.2/4:27.0); 10. Lynn Kanuka (Canada) 8:50.20 (4:23.3/4:26.9);11 Cornelia Burki (Switzerland) 8:53.85 (4:25.7/4:28.2); 12. Eva Ernström (Sweden) 8:57.59 (4:25.8/4:31.8); 13. Christine Benning (Great Britain) 8:58.01 (4:24.4/4:33.7); 14. Lorraine Moller (New Zealand) 9:02.19 (4:28.9/4:33.3); 15. Alison Wiley (Canada) 9:15.35 (4:23.0/4:52.4).

1500: Decker Kayos The Soviets Again

by Howard Willman

When Mary Decker proved she was as good competitively as her uncompetitively-achieved fast times had suggested—and we only found that out when she won the 3000—she moved from “outside medal threat” to favorite.

But her competition would still be three good Soviets: Zamira Zaytseva (3:56.14), Yekaterina Podkopayeva (3:57.4) and Ravilya Agletdinova (3:59.31).

As the 12 runners crouched, awaiting the starting gun, the 30-year-old Zaytseva showed the most anxiety by false starting. The second go-around was fair, and the pack gunned down the backstretch looking for good position. But something was wrong; where was their expected leader?

“I didn’t know if someone else would want to lead, or if they would let me lead,” Decker said. “If someone else wanted to lead, I would have let them. I didn’t want to lead the pace into a strong wind and then find I didn’t have what I needed at the end.”

So she led, Zaytseva on her shoulder and the pack bunched tightly behind her. She reached the 400 in 64.1, a comfortable opener for sub-4:00 types.

Things remained the same through 800 (Decker 2:11.0, a 66.9 circuit), with Gabriella Dorio, Wendy Sly, Podkopayeva and Agletdinova the closest in pursuit. As the pace became one for a kicker, the type which Decker claimed in the 3000, a wonder was raised whether Decker could take this one.

She had lowered her AR to 3:57.12 before the meet, and followed it closely with an AR 1:57.60 at 800 (both solo). But all three Soviets had 800 PRs more than a second better than Decker’s, and the two hanging back were noted 800 competitors. And they looked very relaxed in stark contrast with the forceful motions of Zaytseva.

But still Decker led, and by 1200 the pace had picked up only slightly (65.7, for a 3:16.7). Then the race began. Decker opened up a little down the backstretch and Zaytseva followed. Podkopayeva blasted past Sly and Dorio and attempted to reach the leaders, but couldn’t.

Decker continued her smooth stride and arm motion. With 170m left, Zaytseva bolted around the leader and on the top of the turn repositioned herself along the rail. Barely noticeably, Decker had to shorten one of her strides.

“All the way around the final turn she started getting closer and closer to me,’’ Decker explained. “She moved in on me, and I had to let her go by. Down the stretch, I was getting worried because I couldn’t get my momentum back.”

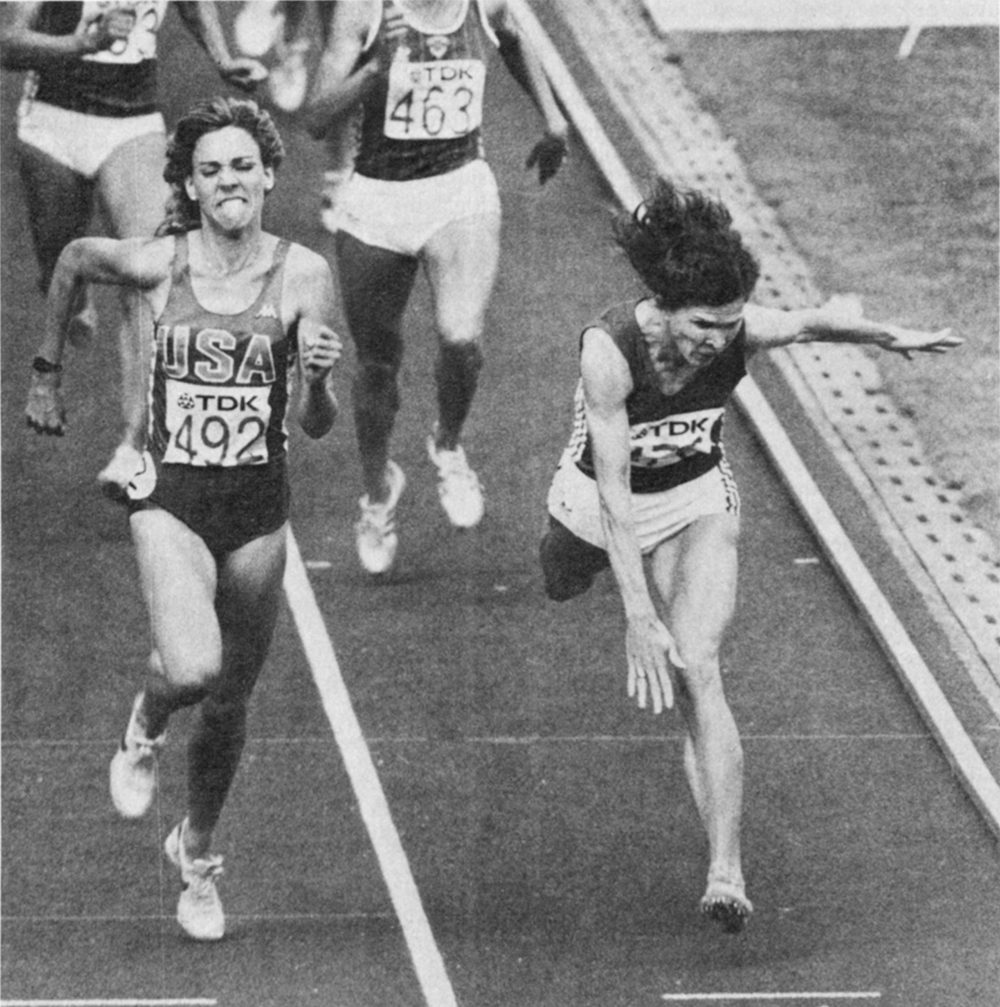

Off the turn, the Soviet had a 2m lead on Decker, who was 4m ahead of Podkopayeva. With 60m left, America’s hope glanced over her left shoulder, and started an all-out drive to catch the hard-working leader.

She was making it up, but not enough. With 20m to go, she was still a meter down. But with 10m left, her momentum had pulled her even with Zaytseva. The challenged Soviet tried to fight hard, increasing her next step. And she began to lunge for the finish line she so desperately wanted to reach.

But her tired state, lengthened stride and early lean were too much, and she fell with 5m to go. Landing on her chest and knees and sliding across the finish with her knees over the rail, as Decker (4:00.90) had captured her second gold in dramatic fashion.

For the first time since ’75, the Soviets would go home from a major meet without a single middle-distance gold.

Indicated bronze medalist Podkopayeva, “Mary has prepared very well this year. I think we will change our tactics and find something new. We will change.”

1500 Results (August 14)

1. Mary Decker (US) 4:00.90 (x, 8 US)

(pace—64.1, 66.9 [2:11.0], 65.7 [3:16.7], 44.2) (finish—60.3, 2:06.9, 3:13.5)

2. Zamira Zaytseva (Soviet Union) 4:01.19

(64.2, 66.8 [2:11.0], 65.7 [3:16.7], 44.5) (60.6, 2:07.1, 3:13.7)

3. Yekaterina Podkopayeva (Soviet Union) 4:02.25

(64.9, 66.6 [2:11.5], 65.6 [3:17.1], 45.2) (61.2, 2:07.8, 3:14.0)

4. Ravilya Agletdinova (Soviet Union) 4:02.67

(64.6, 66.9 [2:11.5], 65.6 [3:17.1], 45.6) (61.6, 2:08.2, 3:14.8)

5. Wendy Sly (Great Britain) 4:04.14

(64.4, 66.8 [2:11.2], 65.7 [3:16.9], 47.3)

6. Doina Melinte (Romania) 4:04.42

(64.7, 66.9 [2:11 .6], 65.7 [3:17.3], 47.2)

7. Gabriella Dorio (Italy)) 4:04.73

(64.4, 66.8 [2:11.2], 65.7 [3:16.9], 47.9)

8. Brit McRoberts (Canada) 4:05.73

(64.8, 67.1 [2:11.9], 65.6 [3:17.5], 48.3)

9. Christina Boxer (Great Britain) 4:06.14; 10. Cornelia Burki (Switzerland) 4:11.61; 11. Ivana Kleinová (Czechoslovakia) 4:15.12; 12. Maria Radu (Romania) 4:19.03.

Mary Decker Happy At Last

by Ruth Laney

Mary Decker must wish she could seal up her week in Helsinki, put it into some kind of time warp and unwrap it a year from now. Everything went that perfectly for her at the World Championships. She managed to run her own races, win them, answer her critics, and give the Eastern Europeans something to think about.

But Helsinki meant more than all that. It also meant that Decker had finally found the secret to maintaining her health and avoiding the injuries that have plagued her career. Knowing how badly debilitated she has been, one almost holds one’s breath. Will she continue her measured dash toward success, or will the old demons—a tendency to fragility compounded by a sometimes self-destructive will to win—conquer her again?

All that remains to be seen, which means that the next year will unfold with a soap-opera breathlessness. Will Little Mary stay healthy and peak in time for the Games? Will she overcome personal setbacks—a broken marriage among them—and concentrate on Olympic gold? Will she find refuge from press, promoters, publicity, and all the other distractions of success? Will she win the gold medals her hometown fans—and the nation—so desperately want for her?

No one, of course, wants those medals more than Decker herself. It promises to be a tough year, ’84. But Decker has proven that she is a tough lady. Physically tough—able to recover from discouraging setbacks time and again. And mentally tough—enough to silence the doubters and give the competition plenty of food for thought.

No one thought Decker could run her usual style of race in Helsinki. Pundits said, “She’s so used to running over here with no competition, leading from the gun, running only against the clock. Over there, she’ll be elbowed, shoved around. She’ll have to hang back with the pack, run a tactical race.”

So what did Decker do? She ran her own race, from the gun, with a minimum of physical contact. Most impossibly, at the point when everyone expected the competition to mow her down on the final straight, Decker dug deep and came up a winner. She even described her stretch run in the 3000 as “relaxed” and “fun.”

That race evened the score with Tatyana Kazankina. As Decker surged home (and Kazankina faded to 3rd), her teeth were gritted in grim determination, but the strain was more apparent than real.

“I felt strong and in control,” she explained. “Sometimes when you come down the straight, you tie up. But tonight I just took a deep breath and relaxed. I haven’t had a lot of practice with my kick at home. But win or lose, tonight’s race was fun. It was fun to have competition. I’ve run faster, but tonight the most important thing was not running fast, but winning.

“The pace started in the 66s. Nobody made a move to go by me. I know I’m strong enough, and I have confidence in my kick. I knew whoever was with me at the end would have to kick.”

The decision to take the lead was logical, she felt: “I thought I had the best chance of running well if I led, because I’ve been a frontrunner for a long time, and I don’t mind leading. I sensed the others wanted me to lead. I don’t mind doing it. I have confidence in my strength right now. Leading is the best way to stay out of trouble. It doesn’t mean I’ll lead in the 1500.”

She did, though. And the second race, four days later, also came down to a stretch run. This time, it was complicated by what Decker called “aggressive” tactics on the part of Soviet Zamira Zaytseva.

“I had to work harder to catch Zaytseva,” Decker said. “In the last stretch, she was clearly ahead of me. I thought, ‘There’s not another chance for four years, at the next World Championships.’ I didn’t want to feel that I’d cheated myself by not trying hard enough.”

Gold medals safely tucked away, the 25-year-old Decker was already looking toward the remainder of the European season. But she took a moment to relish her achievements: “I’m satisfied the doubts have been resolved. I’ve never had doubts, because you can’t be a competitor without a positive mental attitude. There are some who have said, ‘Can she race people?’ To tell you the truth, the feeling is quite different racing people. But I can do it, because I’m a competitor.”

What did Helsinki mean in terms of Los Angeles? “I needed the experience of this meet going into LA next year. I needed the experience of doubling in the 1500 and the 3000. I needed the experience of running under pressure, of running in a structured atmosphere. The atmosphere, and the preparation, and the people—and running a little bit more tactically—are all going to help me next year.”

The fans probably helped, too. Finnish spectators lavished cheers, affection, flowers, flags, and stuffed animals on the Americans—and Decker was one of their favorites. But wonderful as Helsinki was, Decker left no doubt that for her 1984 is still the Big Enchilada.

“Anyone who knows my history knows I’ve never been involved in an Olympics. (She was only 14 in ’72, injured in ’76, and made the ill-fated American team in ’80.) I’ve been running since I was 11, and the Olympics is just an ideal that everyone has. It’s something I’ve never experienced, and I want to experience it.

“I am basically from LA,” says Decker, who moved with her family to Southern California when she was 11 and discovered running there. “Everyone’s so excited about the Games. I’ve got a lot of friends in LA and, even though I hate to do it, I will try to isolate myself to a degree. I will find a somewhat quiet place, if possible, to get away from all the distractions. Because I really feel that I need to concentrate.”

Concentrate and remain healthy. “I’ve had minor injuries this year,” she admits. “Hopefully, over the next year I’ll remain injury-free. I’ll stop racing when I have any pains in my tendons or muscles. In the past, I’ve tried to race through injury. That doesn’t work. Now I stop racing.”

All eyes will be on Mary Decker from now through 1984. If her stars stay in their current conjunction, and she strikes gold in Los Angeles, it seems safe to predict she’ll be America’s Sweetheart—Little Mary, happy at last.

previously in Great Matchups:

Liquori vs. Ryun — The Dream Mile

Geb vs. Tergat — 5 Fabulous 10Ks

Powell vs. Lewis — Beamon’s Record Falls