THEY RATE AMONG the best 10K clashes ever seen: Haile Gebrselassie vs. Paul Tergat at the World Champs of ’95, 97 & 99 and the ’96 and ’00 Olympics. Five major championships in succession over six seasons, with the last a squeaker for the ages. Each time the diminutive Ethiopian outkicked the tall Kenyan. Geb’s margins of victory—1.58 (1.75 ahead of bronze medalist Tergat), 0.83, 1.04, 1.29 and an unreal 0.09—were oh-so-tight every time, but enough to win.

As recounted in the T&FN editions of October ’95, October ’96, November ’97, November ’99 & December ’00, here’s how the races played out:

Gothenburg ’95: 3-Country Affair

by Cordner Nelson

To excel in the World Championships these days, a distance runner must wear a uniform of red, green, and a little white. Runners from Kenya, Ethiopia and Morocco all wear red pants and green tops, although Kenyans have green sides on their shorts and a red-and-white design on their green uppers. These three teams took the first 6 places in each race, with 12 different runners.

[Ed: The following excerpt was the first portion of a combined 5K/10 report; neither Tergat nor Gebrselassie contested the 5000.]

The 10K heats came first, with Kenyans Josephat Machuka and Joseph Kimani dooming themselves to failure. Kimani, whose second-ever track 10 was a 27:28.07 in April, pushed the pace through 19 laps. Then Machuka—officially only 20 years old and holder of the altitude WR at 27:53.0—showed a complete disregard for intelligent conservation of energy. He kicked home in 2:04 for a 27:29.07, a PR by 24 seconds.

The final was three days later. Khalid Skah, the ‘92 Olympic champion, said of the two rash Kenyans, “It was hard to recover after 27:29. They had no chance to succeed.”

With 64.1 laps being WR pace, the race started with a disappointing 70.4 , but it takes only one veto to nullify a tactical pace. American Todd Williams issued his veto after 600m and ran second and third laps of 62.6. With a 60m lead, he settled down to a 28:00 pace, but the others did not catch him until the ninth lap.

Paul Tergat was the first to go after Williams. Old and tall for a Kenyan at 26 and 6-0, Tergat set a road WR for 15K in ‘94 and won the ‘95 World Cross Country. His 63ish laps caught Williams and he led by 10m at 9 laps. “I had to do it,” said Williams. “I had to think about the best way to win a medal.”

As the American disappeared into the second pack 25m behind, defending champion Haile Gebrselassie led the way to Tergat’s heels. The 5-3 Ethiopian, only 23 years old, was already a gold-silver winner in ‘93 and for four days this year held the WR in both the 5 and 10.

As Tergat led swiftly, with the WR holder on his heels, four others of immense ability followed closely. Skah almost hid himself, never leading, hoping for a pace slow enough to conserve his finishing speed. Having resumed training in April after two months out with a stress fracture of his left foot, it “was too late to get my speed.”

Salah Hissou, taller than Skah but with the same Moroccan crewcut, ran behind Skah like an obedient servant.

Tergat continued to lead for most of the first 23 laps—hard, steady running with no surges. Gebrselassie was almost always 2nd. At 23 laps Hissou went past Tergat on the backstretch. Kimani had lost contact on the 22nd lap and Machuka, needing some of the exuberant energy he wasted in the heat, faded on the 23rd.

Hissou led at the bell with the stalker, Gebrselassie, close behind. Skah, who had been lurking inconspicuously, now seemed poised for the kill. Tergat was 4th.

Into the last turn, Gebrselassie launched a wicked, wicked sprint. He shot past Hissou and opened a gap of 5m before Skah could follow. Skah sprinted hard but he could not keep up with the Yifter-like speed of the little Ethiopian. Tergat followed Skah and gained in the stretch. He fought up to Skah’s shoulder but he could not hold Skah’s pace and lost the silver by a meter.

Gebrselassie’s last 200 was a sizzling 25.1—faster, it was noted, than Wilson Kipketer’s impressive close in the 800 final a couple of hours earlier. He won by 10m in 27:12.95 as the first five broke the meet record.

Williams outfinished the group to acquit himself in 9th with 27:52.87, the fastest time by an American in an international championship since Frank Shorter’s 27:51.4 at Munich in ‘72. “I keep getting faster and faster,” said Williams. “But they keep getting faster too. What can you do?”

Gothenburg Results

(August 8) 1. Haile Gebrselassie (Eth) 27.12.05 (WCR) (x, 8 W) (NR)

(2:58.2, 2:45.0 [5:41.2], 2:43.7 [8:24.9], 2:38.0 [11:02.9], 2:43.1 [13:46.0], 2:42.7 [16:28.7], 2:43.0 [19:11.7], 2:44:9 [21:56:6], 2:42.7 [24:39.3], 2:34.7) (13:46.0/13:27.0) (56.3);

2. Khalid Skah (Mor) 27:14.53 NR (9, 11 W)

(2:58.7, 2:45.8 [5:42.3], 2:43.0 [8:25.3], 2:37.9 [11:03.2], 2:43.3 [13:46.5], 2:42.3 [16:28.8], 2:43.3 [19:12.1], 2:44.6 [21:56.7], 2:43.2 [24:39.9], 2:34.7) (13:46.5/13:28.0) (57.6);

3. Paul Tergat (Ken) 27:14.70 (10, 12 W)

(2:58.9, 2:43.1 [5:42.0], 2:43.4 [8:25.4], 2:38.1 [11:03.5], 2:43.5 [13:47.0], 2:42.2 [16:29.2], 2:42.9 [19:12.1], 2:40.2 [21:58.3], 2:40.9 [24:39.2], 2:35.5) (13:47.0/13:27.7) (57.9);

4. Hissou (Mor) 27:19.30 PR (13:48.7/13:32.6); 5. Machuka (Ken) 27:23.72 PR (13:48.3/13:37.6); 6. Kimani (Ken) 27:30.02 (13:46.0/13:44.0); 7. Franke (Ger) 27:49.88 PR; 8. Guerra (Por) 27:52.55;

9. Williams (US) 27:52.07 (2:49.1, 2:42.3 [5:31.4], 2:49.0 [8:19.4], 2:50.0 [11:09.4], 2:49.8 [13:59.0]) (13:59.0/13:53.9); 10. Hayata (Jpn) 27:53.12 PR; 11, Do. Castro (Por) 27:53.42; 12. Watanabe (Jpn) 27:53.82;

13. Silva (Mex) 27:55.34; 14. Mezegebu (Eth) 27:56.06 (3, 10 WJ); 15. Ntawulikura (Rwa) 27:57.92; 16. Gomez (Spa) 27:59.38; 17. Hamaala (SA) 28:00.08; 18. Baldini (Ita) 28:08.39; 19. Pinto (Por) 29:26.42; dnf—Anton (Spa).

Atlanta ’96: Gebrselassie KICKS

by Cordner Nelson

Ethiopia’s Haile Gebrselassie came to Atlanta to win two Olympic gold medals, but he ran into trouble with the toughest imaginable opponent and a barely-legal sprinter’s track as hard as nearby Stone Mountain.

Gebrselassie’s countrymen, precariously living on a razor’s edge, value an Olympic gold more than any other honor. After becoming Athlete Of The Year for ’95, Gebrselassie said, “From now on, every race I do will help me prepare for Atlanta. Only then will I be a big hero like Yifter.”

For the first time since heats were instituted in ’72, no American made the final. Nobody had held out great hope for Brad Barquist or Dan Middleman, but Todd Williams was generally tabbed as the best non-African in the field. He suddenly stepped off the track 18 laps into his heat and declined to be interviewed.

After the Games he explained to the Knoxville News-Sentinel, that blood tests showed he had simply overtrained. “I should have been setting myself up to run a medal race and instead I ended up killing myself,” he said.

Gebrselassie’s quest in the final began at 10:10 p.m. in pleasant temperature with a pleasant lap in 70 seconds. The pack passed the first kilo at a 28:00 pace. After 4 laps, Aloÿs Nizigama, Burundi’s 27:20 veteran, led the pack until they passed 5000m in a leisurely 13:55.22. Then the Kenyan plan unfolded.

Paul Koech started things humming with a lap in 62 and he led them at WR speed for 4 laps before Josephat Machuka spelled him for 3 tours. At 8 kilos (22:01.98) they had covered the last 3000 in 8:06.76, a 27:02 pace. Then the race exploded with excitement.

With 6 laps to go, the third Kenyan burst out of the pack with every intention of stealing the race. Running with fluid grace, Paul Tergat shot away from everybody—except the little Ethiopian. Gebrselassie followed immediately as if the surge had been planned. Salah Hissou of Morocco, until now a threat of the highest order off his 20K road WR and his recent 12:50.80 in the 5000, lost 8m and the other three trailed him by 15.

After Tergat’s 60-flat lap, Hissou had closed to within 5m, but the other three were 40m behind and no other runner was within a straightaway of them.

Tergat was thought to be Gebrselassie’s strongest opponent because of his two World Cross Country championships and his astounding half-marathon record, equal to back-to-back 10,000s in 27:37 plus 2200m. He continued to speed around the red track in 62 seconds, completing a 2:02.3 800 with 3 laps to go.

A disheartened Hissou followed 20m back, now 60 ahead of the second pack. Tergat towed the little red-and-green trailer around the 23rd lap in 62.5, now leaving Hissou 40m behind and completely out of it.

Tergat ran another 62.5, but before he completed it, Gebrselassie unhitched himself and rolled into the lead just before the bell. As in last year’s World Championships, he opened a gap immediately, running 200m in 28.4, and on the last turn he led Tergat by 12m.

Into the homestretch, Gebrselassie looked back then ran to the finish as if in a qualifying heat. Tergat sprinted swiftly and cut the final margin to less than a second, 27:07.34-27:08.17.

Hissou claimed the bronze (27:24.67), while Nizigama (27:33.79) ran away from Machuka (27:35.08) and Koech (27:35.19 PR) for 4th.

Gebrselassie said the track was too hard: “It was like running on a road. It was very difficult to run 25 laps on this bad track. I have never been so tired after an important race.”

Part of his fatigue was caused by the intense pressure from Tergat. Gebrselassie finished with 57.5, 2:00.1 and 1600 in 4:04.8. His closing 2000 was in a world-class 5:05.1, bringing a slow-starting 3000 down to 7:48.6. His final 5000 was an absolutely astonishing 13:11.4, faster than the winning time in every Olympic 5 other than Saïd Aouita’s ’84 time.

Atlanta Results

(July 29): 1. Gebrselassie (Eth) 27:07.34 OR (old OR 27:21.45 Boutaïb [Mor] ’88) (U.S. all-comers record; old 27:25.82 Chemoiywo [Ken] ’95) (WL) (x, 6 W) (2:49.7, 2:43.0 [5:32.7], 2:46.1 [8:18.8], 2:48.5 [11:07.3), 2:48.6 [13:55.9], 2:39.9 [16:35.8], 2:42.8 [19:18.6], 2:43.7 [22:02.3], 2:33.8 [24:36.1), 2:31.3) (13:55.9/13:11.4) (29.1,57.5, 2:00.1, 4:04.8, 5:05.1, 7:48.6);

2. Tergat (Ken) 27:08.17 (7, 8 W) (57.9); 3. Hissou (Mor) 27:24.67; 4. Nizigama (Bur) 27:33.79 (13:55.22); 5. Machuka (Ken) 27:35.08; 6. Koech (Ken) 27:35.19 PR; 7. Skah (Mor) 27:46.98; 8. Ntawulikura (Rwa) 27:50.73; 9. Franke (Ger) 27:59.08; 10. Brown (GB) 27:59.72 PR; 11. Quintanilla (Mex) 28:09.48; 12. Hhawa (Tan) 28:20.58; 13. Anton (Spa) 28:29.37; 14. C. de la Torre (Spa) 28:32.11; 15. Gómez (Spa) 28:39.11; 16. Kaldy (Hun) 28:45.48; 17. Bikila (Eth) 28:59.15; 18. Baldini (Ita) 29:07.77 (2:48.32);… dnf—Al-Qahtani (Sau), Evans (GB).

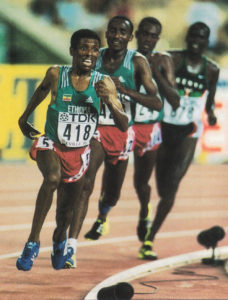

Athens ’97: Danger, Haile Explosive

by Cordner Nelson

Haile Gebrselassie’s opponents must think of him as some sort of terrorist—so innocent and friendly until that final deadly explosion. A tiny man with a huge heart and an engaging smile, Gebrselassie has now helped himself to every championship and record a 24-year-old 10K man can win.

For a while it appeared as if the two-time defending champ wouldn’t even show. After reclaiming his World Record with a 26:31.32 in Oslo in early July, he noted that the Worlds were no longer “anything special.” Not being enamored of the Athens air or sprint-tailored track, he said he would pass.

But he eventually relented, and when the final began he let the race develop slowly in the classical fashion, gradually tiring the slower runners while the elite few awaited his final explosion.

They circled the red track in a leisurely manner, perhaps because the weather was too warm and the track was too hard and the final was too soon after the heats and too close to the lure of big money at Zürich. Or perhaps they knew they could not beat Gebrselassie at any pace, so why suffer?

For six laps they followed 19-year-old prospect Saïd Berioui in Morocco’s red with green sides. Then the national anthem of Kenya resounded for the steeplechase victory ceremony and the three Kenyans made their move as if on cue. Dominic Kirui, a novice 10K runner at age 30, led for 5 laps, including the eighth in 63.56, which said good-bye to a third of the pack.

After leading through 5000m in 13:58.79 and 6000 in 16:49.31 (a 28:02 pace), Paul Koech began a real surge. Wearing Kenya’s black with green trim and side of white with red trim, the 28-year-old, fifth-fastest of all time, ran four laps in 4:15.47. Only 7 others stayed close for one lap and two of those were gone a lap later.

Koech led for another four laps but his time slowed to 4:22.30 as all 6 runners waited for the explosion, including the little man in the red shorts and green vest of Ethiopia.

With two laps to go the detonation seemed overdue. Behind Koech, three runners ran abreast: Gebrselassie, of course, flanked by Moroccan Salah Hissou (who had broken Gebrselassie’s former WR after the Olympics last year), and surprising veteran Domingos Castro of Portugal, the year’s fastest marathoner.

Paul Tergat, the tall and powerful Olympic silver medalist, moved on the curve alongside Castro, who began to fade. On the backstretch, Gebrselassie moved smoothly to 2nd place followed by Hissou and Tergat.

Koech turned his head back as if to ask, “What’s going on? When will it happen?” and almost immediately it did happen. The Ethiopian exploded dramatically, opening an immediate gap of 5m over Hissou and Tergat. Around to the bell, Tergat ran hard and led Hissou but he trailed the speeding Gebrselassie by 10m.

On the last backstretch the gap was 15m and Hissou followed Tergat by 10. Then it was the Olympic finish all over again, with Gebrselas sie (27:24.58) coasting in at high speed while Tergat (27:25.62) gained in the stretch to finish only 8m behind and 15 ahead of the dispirited Hissou (27:28.67).

“Before I came here, I was a little afraid that the track would be hard,” the winner said. “But it turned out to be better than in Atlanta. I expected more competition from the Kenyans and Moroccans. My win was very easy, unlike the one in the Olympics. Besides, that medal is more important-even though this one is not bad either.”

Gebrselassie won his third straight title with an explosive final 600 in 1:24.6, a 1:52.8 pace. His actual final 800 with half a lap at 10K pace was 1:57.0. His last lap split out at 27.29 and 28.58 for a 55.87 total.

Small wonder his opponents are terrorized, but they may have some relief ahead, for he said, “I don’t care anymore about the World Championships. If someone beats my World Record, I will start to train again.”

Asked by Greeks—as many Athens winners were—where he would like to see the 2004 Olympics held, Gebrselassie split his vote between Cape Town and Stock holm, but threw out what amounted to more than a hint about his future.

“I hope the 2004 Olympics take place in Cape Town because it is in Africa,” he said, “but Stockholm might be better for me since by then I will be running the marathon.”

Neither U.S. runner made the final. Dan Middleman stayed with the pack for 17 laps in the first heat, while Brad Barquist lost contact after 5 laps of the second.

Athens Results

(August 6) 1. Haile Gebrselassie (Eth) 27:24.58

(2:56.7, 2:43.9 [5:40.6], 2:47.0 [8:27.6], 2:44.6 [11:12.2], 2:47.3 [13:59.5], 2:50.4 [16:49.9], 2:38.4 [19:28.3], 2:42.9 [22:11.2], 2:42.7 [24:53.9], 2:30.7)

(13:59.5/13:25.1) (27.29, 55.87, 1:57.0)

2. Paul Tergat (Ken) 27:25.62

(13:58.79/13:26.83) (27.5, 55.2)

3. Salah Hissou (Mor) 27:28.67

(13:59.5/13:29.2) (29.7, 58.1)

4. Koech (Ken) 27:30.39 (13:59.0/13:31.4) (59.3); 5. As. Mezegebu (Eth) 27:32.48 (13:59.3/13:33.2) (60.0); 6. Do. Castro (Por) 27:36.52; 7. Jifar (Eth) 28:00.29; 8. Rey (Spa) 28:07.06; 9. Baldini (Ita) 28:11.97; 10. Wilson (Aus) 28:20.16; 11. Maase (Hol) 28:23.20; 12. D. Kirui (Ken) 28:28.13; 13. Zitouna (Mor) 28:29.09; 14. Ramaala (SA) 28:33.48; 15. Chimusasa (Zim) 28:55.29; 16. Eich (Ger) 28:59.34; 17. Berioui (Mor) 29:22.05; 18. Ramos (Por) 29:49.00;. .. dnc—Mourhit (Bel), Takaoka (Jpn).

Seville ’99: Geb Wins, But No Sweep

by Dan Lilot

Ostensibly due to field size, but perhaps to save the athletes from a grueling heat in oppressive conditions just three days before the final, qualifying rounds were canceled for the first time since the ’87 edition. Nevertheless, no one was anxious to hammer as the final got under way.

Despite the slow pace 3-time defending champ Haile Gebrselassie was always near the lead, running in the outside of lane 1.

Also near the front were the WR holder’s countrymen, Girma Tola, Habte Jifar and Assefa Mezegebu, along with Kenyans Paul Tergat, David Chelule and Benjamin Maiyo.

After 11 laps, Maiyo moved into the lead and made the first real move. It was not long-lived, however. Geb led a bunched pack through halfway in 14:17.17.

The lead changed hands several times over the next few laps, with Maiyo surging but without the pace needed to drop any of the main contenders. Geb and Jifar occasionally took the lead, apparently to slow the pace. Surprisingly, the Kenyans did not seem to mind and were content to let the race play into Geb’s hands.

Finally, with 7 laps remaining, Chelule took the lead and injected some pace, touring the next circuit in 62. Chelule continued to lead through 8km (22:43.62), leaving only the Kenyans, Ethiopians and recent Euro Recordsetter Antonio Pinto of Portugal in contention.

With a mile remaining, Maiyo led, maintaining a strong tempo, but failed to drop any of the favorites. Geb followed closely, looking entirely unpressed.

Pinto used his marathoner’s strength and surged to the front with a kilo to go, followed closely by Geb, Tergat and the three other Ethiopians. Coming up on the bell, Geb, Mezegebu and Tola stormed into the lead, with Tergat following and the rest of the field dropping back.

Down the backstretch it looked to be an Ethiopian sweep as Geb shifted into a gear only he owns, running the final 200 in 26.3 to win his fourth straight title in 27:57.27, the slowest winning time since the first Worlds in ‘83.

Tergat closed almost as well, however, running 27-flat for his last 200 in ripping up the homestraight to capture the silver by a hair over Mezegebu, 27:58.56–27:59.15. Pinto also finished strongly, splitting Tola and Jifar.

Said Geb, “As soon as I made my move in the final lap I knew there was nothing they would be able to do to catch me.”

Seville Results

(August 24) 1. Haile Gebrselassie (Eth) 27:57.27 (14:17.17/13:40.10) (26.3, 54.4, 1:55.5, 2:57.7, 4:04.0); 2. Paul Tergat (Ken) 27:58.56 (14:19.0/13:39.5) (27.0, 55.1); 3. Assefa Mezegebu (Eth) 27:59.15 (14:18.2/13:40.9) (28.1, 56.0) 4. Tola (Eth) 28:02.08 (30.6, 58.6); 5. Pinto (Por) 28:03.42; 6. Jifar (Eth) 28:08.82; 7. Maiyo (Ken) 28:14.98; 8. Maase (Hol) 28:15.58; 9. Chelule (ken) 28:17.77; 10. Skah (Mor) 28:25.10; 11. Ramaala (SA) 28:25.57 (14:17.4/14:08.2); 12. Takaoka (Jpn) 28:30.73; 13. N’Tyamba (Ang) 28:31.09 NR; 14. Molina (Spa) 28:37.19; 15. Sghir (Mor) 28:41.49; 16. Bérioui (Mor) 28:46.77; 17. Ezzher (Fra) 28:47.01; 18. Takao (Jpn) 28:49.95: 19. J. Martínez (Spa) 28:55.87; 20. Trifune (Jpn) 29:04.09; 21. Brad Hauser (US) 29:18.21; 22. Julian (US) 29:20.31;… dnf-Brown (GB), Culpepper (US).

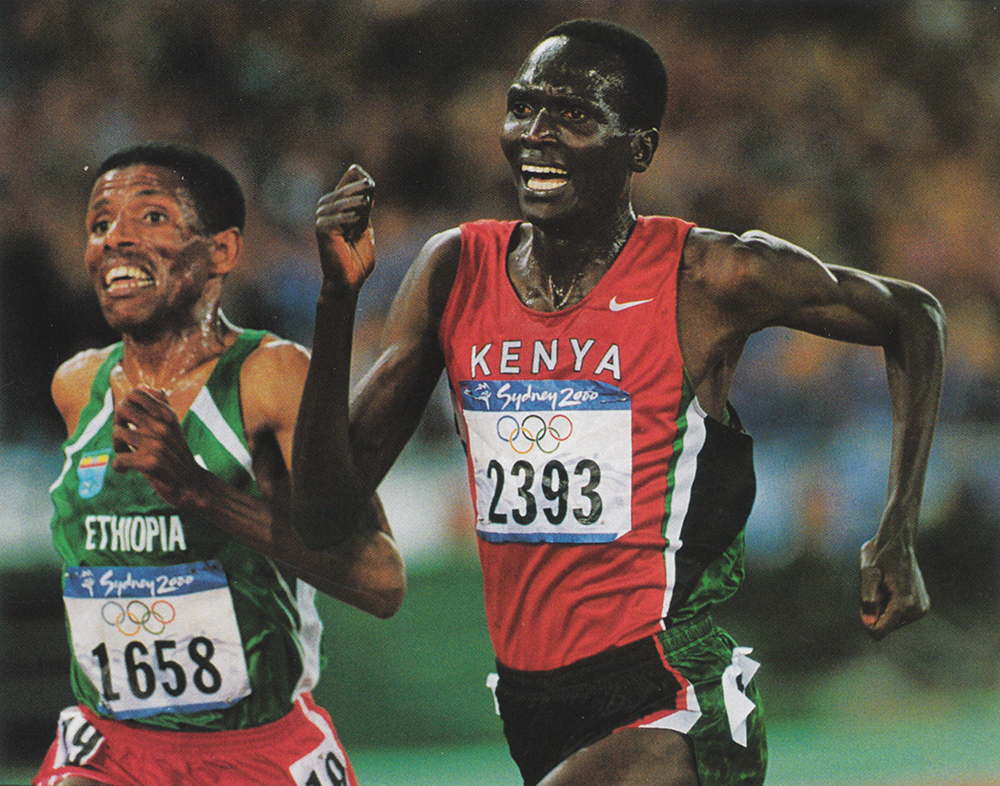

Sydney: Geb Wins A Battle For The Ages

by Dan Lilot

It was one for the history books. You know, those dusty volumes you found in the library as a kid that no one but you ever checked out. The ones that recounted the stories of Nurmi, Zátopek, Viren and Yifter; names and races that seemed so far away. You never thought in your lifetime that you would see anything that could match, or, believe it or not, surpass the tales of such legends.

But now you can’t help but believe that they will be recounting the races of Haile Gebrselassie—and especially his battles with Paul Tergat—for years to come.

The careers of the two rivals have been defined by one another. Tergat, the 5-time World Cross Country champ, forced Geb to forgo any more races over hill and dale after his crushing ‘96 defeat. Gebrselassie, the four-time World 10K champ, relegated Tergat to a frustrated two silvers and one bronze in track’s biggest biennial meet. When the Kenyan broke Geb’s world 10K record in ’97, the Ethiopian simply came back the next year and set the still-standing mark of 26:22.75.

But perhaps most memorably, it was their battle in the Olympic Games in Atlanta that encapsulated their rivalry. Tergat ran one of the bravest races in history, surging to the front with 5 laps to go and pushing Haile to the limit, but Geb simply decided that no one was going to beat him on that day.

And so it was Gebrselassie vs. Tergat once again in Sydney, in what each claimed would be his final championship track competition. [Ed: for Tergat it turned out to be true, but Geb went on to run in two more Olympic 10Ks, taking 5th in Athens and 6th in Beijing.] The results in the history books will list Geb as winning the closest Olympic distance race ever, 27:18.20–27:18.29. But if that’s all they tell, they will be cheating the next generation of track fans.

The final (?) battle between the two arch-rivals was indeed one for the ages. Geb’s victory, capped by a thrilling sprint finish, may well end all discussion as to who is the greatest distance runner of all time.

Taking advantage of the near-perfect weather, Burundi’s Aloÿs Nizigama sped a 62.63 first lap. Tucked behind the leader, where he would stay for virtually the entire race, was Geb. Nizigama continued to crank out a sub-27 pace through 5 laps (5:23.31), stringing the pack out behind him.

Tergat’s teammate Patrick Ivuti took the lead after 3km, but the pace then began to dawdle. After 11 laps, Ivuti moved out to let someone else lead. Nizigama reluctantly retook the pacing job and led the field through halfway in 13:45.8.

Ivuti then kept the tempo honest for a few more tours of the oval, but a 73.5 circuit for lap 16 forced Nizigama back into the lead.

But the real racing did not begin until third Kenyan John Korir, theoretically only 18 but holder of the fastest time ever run at altitude, dropped the hammer down with less than 7 laps remaining. A pair of 63-second circuits cut the single-file pack down to Geb, Tergat, Mohammed Mourhit of Belgium, Moroccan Saïd Bérioui, Ivuti and Ethiopian Assefa Mezegebu.

Geb briefly took the lead and slowed the pace with 4 laps remaining, but Korir snatched it right back as Bérioui and Mourhit fell off. From this point until just before the bell the pace was forthright, but not enough to drop anyone else. The ordered remained Korir, Geb, Tergat, Mezegebu and Ivuti.

Approaching the bell, Mezegebu moved up to Tergat’s shoulder, effectively boxing him in. Were Geb to make a break at this point, Tergat could only be too slow to respond. It looked as if they were handing the race to Haile.

But Geb didn’t move. Instead, it was Tergat who made the surprise break. Jumping sideways from behind Mezegebu with 250m to go, the tall Kenyan sprinted into the lead and beat Geb to the rail. Coming off the turn, Geb moved slightly wide and began to gain on the leader, but only slowly.

Not until 50m remained did he draw even with Tergat, but he could not get by. Giving it all they had, both athletes went to teeth, the effort almost palpable. Approaching the line, Tergat began to tie up, leaning too early, and Geb dipped past in the final meters. Mezegebu was the next best sprinter, garnering the bronze in 27:19.75.

Citing an Achilles problem which had bothered him much of the year, Geb explained, “I did not know if I should compete here at Sydney and then at the last moment I decided to come here and try. Now I’m very happy.” (Continued below)

Abdi Abdirahman and Meb Keflezighi ran PRs of 27:46.17 and 27:53.63 to finish 10th and 12th for what was actually the best finish ever by a pair of U.S. runners. Third American Alan Culpepper was ill and finished last in his heat.

Neither of the American finalists was particularly happy, despite the PRs. “I could have run better,” said Abdirahman. “Those guys work hard. I just didn’t work hard enough.”

Said Keflezighi, “It was a rough race. When they surged with 10 laps to go, I was just not there. I’m just coming back from sickness and this is the first day I felt fine. I felt good early in the race but at the end they picked it up and they made the gap.”

Sydney Results

(September 25): 1. Haile Gebrselassie (Eth) 27:18.20 (13:46.1/13:32.1) (13.7, 25.4, 56.4, 2:01.7, 3:05.1, 4:09.6); 2. Paul Tergat (Ken) 27:18.29 (13:46.6/13:31.5) (12.7, 26.0, 2:01.4, 3:05.0, 4:09.3);

3. Assefa Mezegebu (Eth) 27:19.75 (13:46.8/13:33.0) (13.7, 58.0, 2:02.9, 3:06.4, 4:10.9); 4. Patrick Ivuti (Ken) 27:20.44 (13:47.1/13:33.3) (27.3, 58.2, 2:03.2, 3:06.7, 4:11.4); 5. John Korir (Ken) 27:24.75 (3, 3 WJ) (13:46.9/13:37.9) (31.3, 63.3, 2:08.7, 3:12.2, 4:16.2); 6. Saïd Bérioui (Mor) 27:37.83; 7. Toshinari Takaoka (Jpn) 27:40.44 PR; 8. Karl Keska (GB) 27:44.09 PR; 9. Aloÿs Nizigama (Bur) 27:44.56; 10. Abdi Abdirahman (US) 27:46.17 (AL) (12, x A); 11. Girma Tola (Eth) 27:49.75; 12. Meb Keflezighi (US) 27:53.63 PR; 13. David Galván (Mex) 27:54.56; 14. José Ramos (Por) 28:07.43; 15. Katsuhiko Hanada (Jpn) 28:08.11; 16. Samir Moussaoui (Alg) 28:17.25; 17. Rachid Berradi (Ita) 28:45.96; 18. José Ríos (Spa) 28:50.31;… dnf—Enrique Molina (Spa), Mohammed Mourhit (Bel). ◻︎