PLEASE JOIN US for a quick journey through the last 75 years in track & field. The following vignettes are not intended to represent the most important happening in each year of our existence, nor are they items directly from the pages of Track & Field News. Rather, they’re pieces intended not only to bring back warm memories for the longtime subscriber, but also to give the youngsters a hint at just how much our sport has developed in the last three-quarters of a century.

(Note: The pieces covering 1948 through 1997 originally appeared in the 50th Anniversary Edition, February ’98.)

1948 — California’s Boy Wonder

In May of ’48 T&FN was a struggling young publication and Bob Mathias’s high school coach was struggling to convince him to try the decathlon, telling him that by ’52 he might be good enough to make the Olympic team. One of the country’s best prep hurdlers, Mathias had never even tried to vault or throw the javelin.

Although he wasn’t great at any single event, Mathias proved to be adept at all of them, and in his second 10-eventer produced the world’s best score since ’40. He was off to the Games four years early, and after two days of slogging through unimaginable rain and mud (including a javelin runway lit by flashlights) he was Olympic champion at 17.

1949 — Patton Changes His Mind

Mel Patton had a fabulous ’48 campaign, running the first legal 9.3 for 100y, winning the Olympic 200 title and adding another gold in the 4×1. Shocking it was, then, when the January ’49 issue of T&FN headlined, “Mel Patton Quits Track.”

Fortunately, he relented, and was even better in ’49, going undefeated in both dashes, and running 20.2 for the 220 straight, breaking Jesse Owens’s 14-year-old WR. He also anchored his USC teammates to a pair of WRs in the 4×2. But he never ran again after winning both NCAA dash titles.

1950 — Statistics Get Codification

Few in the United States knew, and probably even fewer cared, but an August meeting in Brussels laid the framework for bringing some order to track’s statistical chaos with the formation of the Association Of Track & Field Statisticians (ATFS), with Roberto Quercetani as the first president. To this day, the ATFS serves an essential role in keeping track’s international lists — both yearly and all-time — in tremendous working order.

1951 — Fabulous Fanny’s Farewell

WWII stole most of the best years of Fanny Blankers-Koen’s career, but given her one real shot at Olympic glory, she had been the big story of the ’48 Olympics, winning an unprecedented four gold medals in the 100, 200, 80H and 4×1.

When the ’52 Games rolled around, she would be 34, probably too old to make much of an impact, and as it turned out, medication she was taking rendered her too dizzy to be effective. But just a year before, she showed that she wasn’t really too old, even at 33, as she produced the final World Record of her career, in the pentathlon.

1952 — Zátopek’s Amazing Triple

Emil Zátopek was already a distance legend before he came to the Helsinki Olympics. With multiple WRs and an Olympic gold (‘48 10K) already under his belt he decided to do something unprecedented.

First, running with his trademark look-of-agony style, he won the golds in the 10,000 and 5000, but that had been done before. But only two days after his 5K triumph he entered his first marathon. Indeed, he had never even run half that far in training.

In midrace he asked the favorites, “Are we going fast enough?” He was, but they weren’t, and when he was done, the indomitable Czechoslovakian had his third gold.

The ovation he received on his victory lap may be the greatest ever heard.

1953 — The Jav Learns To Fly

As an engineering student, Bud Held brought a unique perspective to the javelin, and he and brother Dick ended up designing more aerodynamic spears than had previously been used. Fatter ones that floated better. A three-time NCAA champ for Stanford (1948–50), Bud was experimenting with a new hollow implement by ’53, but was still employing a solid model of Held design when he became the first to break both the 80m and 260-foot barriers with a throw of 263-10 (80.42) in the summer of ’53.

1954 — The 4:00 Barrier Falls

Oxford, England, May 6 — Nobody actually heard all of one of the most famous announcements in track, which began in reserved English fashion, “Ladies and gentlemen, here is the result of event 9, the one-mile: 1st, No. 41, R.G. Bannister, Amateur Athletic Association and formerly of Exeter and Merton Colleges, Oxford, with a time which is a new meeting and track record, and which — subject to ratification — will be a new English Native, British National, British All-Comers, European, British Empire, and World Record. The time was 3…”

Roger Bannister had run 3:59.4, and the crowd drowned out the rest.

1955 — Flying High In Mexico

If people — T&FN included — had paid close attention to what happened at the ’55 Pan-American Games in Mexico City, the record-breaking exploits of Beamon, et al, at the ’68 Olympics wouldn’t have come as a surprise at all. No event better typified the aid given by more than 7000ft of altitude than the 400, where Lou Jones (45.4) and Jim Lea (45.6) both broke the WR of 45.8, even though it was only March and they had previous PRs of just 46.4 and 46.3.

“When was the last time they measured this track?” was their question after the race was over. Herb McKenley, at the time the owner of the only sub-45 relay leg ever, saw the race, shook his head and said, “Now I’ve seen everything.” Nah, everything didn’t come until ’68.

1956 — Big Year For Barrier-Busting

Two of track & field’s biggest barriers, 4:00 in the mile and 60-feet in the shot, had fallen two years previously, but when it came to overall barrier breaking (and sheer number of records), the Melbourne Olympic year is tough to top.

Willie Williams produced the first 10.1 in the 100, ending a long string of 10.2s that had begun with Charlie Paddock way back in 1921. (Williams, by the way, wasn’t an Olympian. He did his best running during the summer months, but the Trials for a November/December Games were held in June!)

The Trials may have been held early, but that didn’t stop the breaking of the 50-second barrier in the 400H (49.5 for Glenn Davis) and 7-feet in the high jump (7-½) for Charlie Dumas. At the Games themselves, the javelin’s 280-foot barrier fell to Egil Danielsen (281-2/85.71) and Australia’s women (44.9) became the first to break 45-flat in the 4×1.

1957 — The Worst Nationals Ever

“AAU Meet Fouled Up” read the headline in T&FN after the nationals wrapped up in Dayton, Ohio. “Reverberations of this meet will be heard for years to come,” we said. “Badly staged, with unfavorable physical conditions and unbelievably bad officiating.

The most egregious errors came in the 220 and 440, where the staggers were mismeasured. In the 440, no two runners ran the same distance and the winner ran only 432y. There was no finishline camera, and misplacings were rampant.

Marks were lost in the discus and hammer when markers were knocked over, and the shot sector was too small, with some legal puts hitting a wall. Spectator aids were nonexistent, the announcing abysmal.

Famed track journalist Maxwell Stiles wrote in the Los Angeles Mirror-News, “Now is the time for the dissolution of the AAU, and the organization of another group with similar functions, powers and responsibilities but without the arrogance, the hypocrisy, the stupidity and the incompetence of the one we have now.”

1958 — Poster Boy For The Wild Bunch

A prodigy if ever there was one, Herb Elliott lost only one mile race in his whole life, and that was an age-group race to someone three years older. He set multiple WRs in the 1500 and mile, the last of them set in winning the ’60 Olympic title in a gutsy bit of frontrunning.

This from a guy who smoked 30-40 cigarettes a day in high school and when on tour was known to consume more than his fair share of suds. His first tour outside Australia came in the summer of ’58, and despite a less-than-stiff training regimen he produced the biggest lowering of the mile WR in the modern era, from 3:57.2 to 3:54.5.

He eschewed prerace handshakes, saying, “To shake hands with one’s opponents before a race and wish them luck is hypocritical. I don’t want to talk to them and the last thing I want to do is shake their hands because it would break down my purposefulness.”

1959 — Cold War Heats Up

Now we know why the Penn Relays are in April. The ’59 U.S.-USSR dual was held at Franklin Field in July, with temperatures approaching 90, and humidity reaching 60%.

American distancemen floundered in the oppressive conditions (their Soviet counterparts did not), particularly Bob Soth in the 10K. About 20 laps in, Soth started leaning backwards, leading our George Grenier to write, “It is so characteristic of impending complete physical collapse that it indicates that officials are unaware of what happens to athletes. It verges on the sadistic when you consider Soth ran 3½ laps in his debilitated state and no one moved to help.”

After a 2:07.8 lap he collapsed and was rushed to the hospital. When he awoke his first words were, “Did I finish?”

1960 — Wondrous Wilma’s Games

After she won a relay bronze at the ’56 Games, 16-year-old Wilma Rudolph said, “At the next Olympics I’m going to win at least one or two of those gold medals for me and my country.”

She went even one better in Rome, becoming the first American woman ever to win three golds, as she captured the 100 (after equaling the WR of 11.3 in the prelims) and 200, then anchored the U.S. 4×1 in WR time. At an Olympics where the men’s team was highlighted by some notable failures, “Wondrous Wilma” became the nation’s darling.

1961 — A Touch Of Glass

At one time or another, vaulting poles were probably made of every kind of wood imaginable, with bamboo taking over as the century began. Aluminum came into prominence after WWII, but people were already experimenting with fiberglass in the late-’40s. Not until ’61, however, did a World Record fall to a glass vaulter, when Oklahoma State’s George Davies cleared 15-10¼ (4.835) at the Big 8 meet.

John Uelses cracked the 16-foot (4.88) barrier the next year, and a new event was born, with the 17-, 18-, 19- and 20-foot ceilings all to fall.

1962 — USC String Stopped At 104

There was a time when the men of Troy were synonymous with collegiate track excellence. Like 1935–43, when USC won 9 straight NCAA team titles, and probably would have won more if WWII hadn’t gotten in the way. As the war wound down, Cal Tech beat the Trojans in a dual in ’45. But for almost 20 years thereafter, the Angelenos were unbeatable in dual meet competition, going 104 meets without a loss (including a tie with Michigan State in ’49).

But in the early ’60s, Bill Bowerman’s Oregon team was in ascendancy, and when the Ducks visited the Coliseum in April, the result was a 75–56 runaway for the northerners. The list of legendary stars who participated that day is boggling. It includes Harry Jerome, Rex Cawley, Dyrol Burleson, Jerry Tarr, Mel Renfro and Dallas Long. Oregon went on to win its first-ever NCAA title that year.

1963 — The Goo Under Your Shoe

Cross country runners who kvetched about the mucky conditions at the USATF Cross Country are all too young to remember there was a time when running on tracks could be similarly soggy.

The first big change came at the ’63 AAU Championships, when the U.S. Rubber Company laid 360 tons of a mixture of rubber, asphalt and crushed stone an inch and a half thick in St. Louis. That the new concoction was fast was evidenced early, when Bob Hayes ran history’s first 9.1 for 100y in the semis. Hayes, who had already run 9.3 on 10 occasions, said, “Those 9.3s seemed faster.”

Such is the magic of synthetic tracks. “I wish they made all the tracks like this,” concluded Hayes.

1964 — The Kid Beats The Russians

If there was one thing you could count on in the old U.S.-USSR series, it was that the Soviet men would dominate the 10,000. Until gawky little Gerry Lindgren, just 18 years old, got his chance at them. Forsaking his usual go-out-hard routine, the recent high school grad bided his time for the first 15 laps, then U.S. coach Sam Bell yelled, “If you feel alright, go on around.”

Go the little Washingtonian did, winning by more than 20 seconds, running 29:17.6 in only his second 10K ever. “When I saw the communist emblem with the hammer and sickle on the jersey of the Russian runners, I knew it was more than a race to see who could get to the finish line,” he said. “I knew it was a race between men’s minds and different ways of life. I wanted to do something.”

1965 — NCAA & AAU Go To War

Dissatisfaction with the way the AAU governed track was long a sore spot with the nation’s collegiate coaches, and in ’61 the National Collegiate Track Coaches Association was initiated as a reform group. The AAU began to make changes, but control of the NCTCA was soon co opted by the NCAA, which formed the U.S. Track & Field Federation (USTFF) as a parallel organization. Peace was declared during the Tokyo Olympic period, but in the fall of ’64 war broke out. In ’65, politics would overshadow proper competition.

The biting issue was over sanctioning of meets, with the NCAA now declaring that collegiate athletes couldn’t compete in meets that didn’t have a USTFF sanction. And the AAU declared its sole right to sanction open meets. Effectively collegians who competed in open meets risked suspension by the NCAA. A comprehensive T&FN survey of the nation’s collegiate coaches found that 71% did not support the NCAA position. In the final analysis, as is so often the case, the athletes themselves saved the day. A handful of brave collegians, with Gerry Lindgren the high-profile performer, decided to call the NCAA’s bluff, and ran in the AAU Championships (Lindgren’s WR 6M race). The NCAA president then said there was no danger of anyone’s losing eligibility.

With Lindgren enjoying folk-hero status in the Pacific Northwest, his federal representatives took strong interest in the situation, and as the year wound down, the U.S. Senate was sponsoring an arbitration process between the AAU and NCAA. It wasn’t the last shameful episode in the alphabet wars, but the worst of it was over.

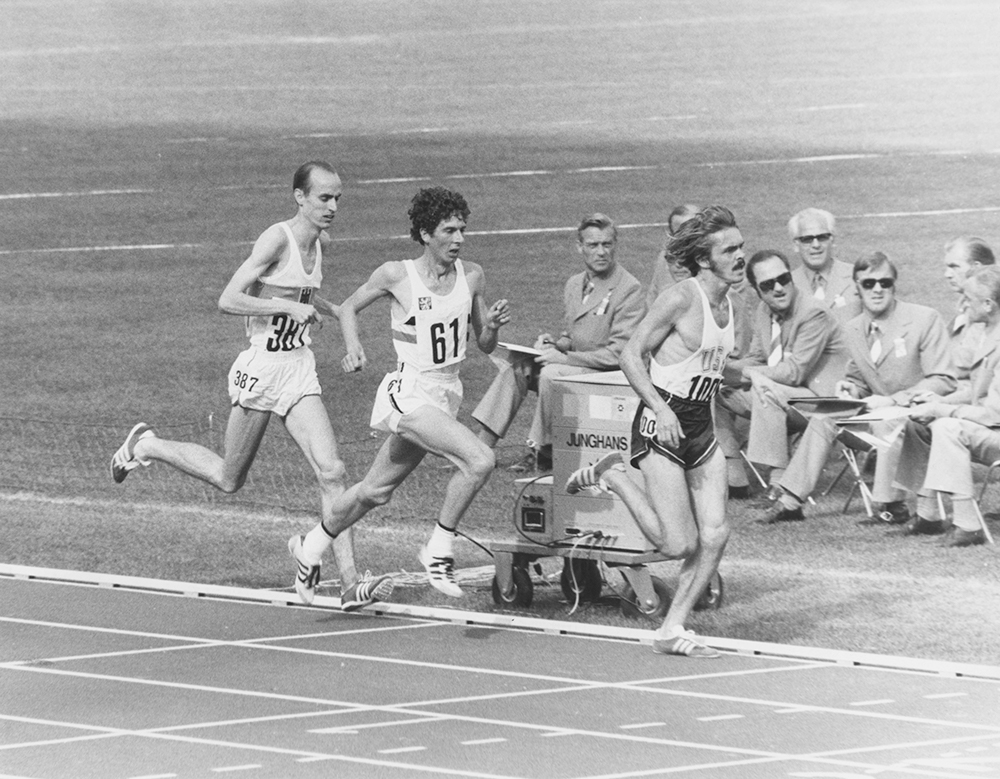

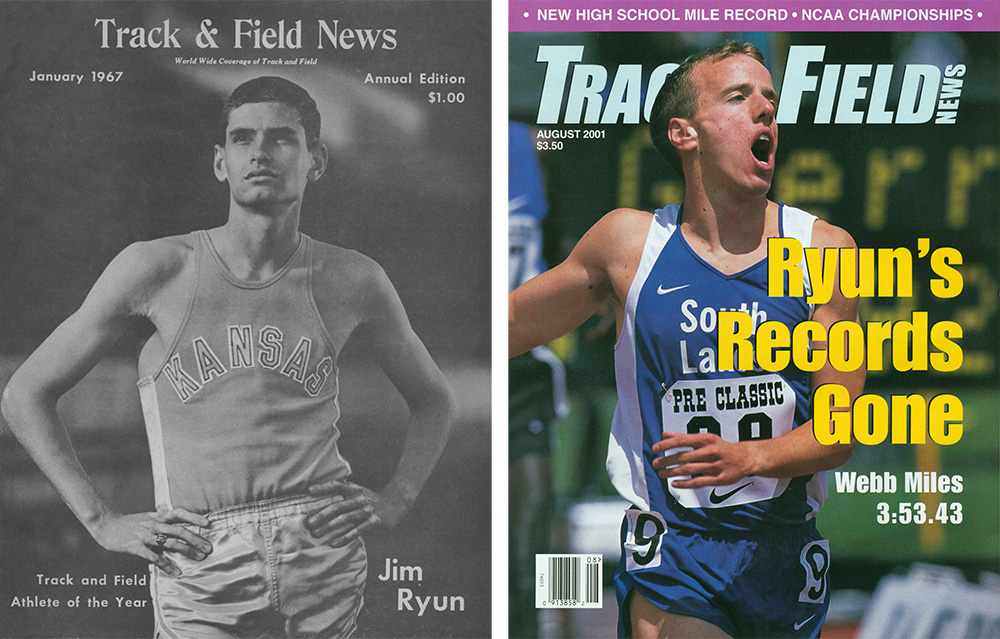

1966–1967 — The Jim Ryun Era

That Jim Ryun was a special talent was obvious when he made the ’64 Olympic team as a prep junior. He was even better in ’65, but once he moved on to Kansas, he became one of the most potent middle-distance forces ever seen, and was our Athlete Of The Year twice in a row.

Showing speed nobody suspected, he ran the fastest 2-lapper ever in the spring of ’66: 1:44.9 for 880y. Obviously ready for big things in the mile, he whacked a huge 2.3 seconds from the WR with his 3:51.3.

In ’67, running virtually solo, he lowered the mile mark to 3:51.1, then a few weeks later went head-to-head with Kip Keino in a 1500. In a real race, no rabbits. When he was done, he had produced the biggest lowering of the 1500 record ever, 2.5 seconds, to 3:33.1.

After a slow start, he ran his last 400 in 53.3, last 800 in 1:50.5 and last 1200 in a scintillating 2:46.6.

1968 — Beamon Jumps Into History

You won’t find it in the dictionary, but it’s the rare sports fan who doesn’t know the meaning of the word “Beamonesque.” What Bob Beamon did was simply bypass the long jump’s 28-foot (8.53) barrier en route to crashing through to 29 (8.84) with his 29-3½ (8.90).

Never mind that dispassionate scientific types-taking into account the extreme altitude and likelihood that the jump was illegally wind aided-now think it was probably just a mortal 28-foot jump under real conditions. It was a performance which shocked the world, and left officials forced to rummage for an old-fashioned tape, because their fancy new sighting device wasn’t designed to go that far.

1969 — T&FN Urges Steroid Policy

More than a few athletes used anabolic steroids at the Tokyo Olympics in ’64; many did at Mexico City in ’68. Nobody questioned the increased performance level which came with their usage. But were the negative aspects—both physical and ethical-so strong that they should be formally banned? That was a question we asked in I April:

“The use of anabolic steroids is unquestionably a prominent development—if not already an important issue-in track & field today, one which has basically been ignored and one which obviously isn’t going to go away by kicking it under the carpet.

“It is T&FN’s opinion that track & field officialdom should take some action. Organizations such as the NCAA, AAU, IAAF and IOC should conduct extensive research into the subject and form a definitive policy. If these bodies determine that taking steroids is legitimate, they should be on record stating as much so that athletes may take them without fear or stigma attached.”

1970 — Chi Does It All

Taiwan’s Chi Cheng was the outstanding women’s performer of the ’69 season, but what she did that year pales in comparison to her exploits the next year.

Competing no fewer than 83 times in a marathon campaign in the sprints, hurdles and long jump, she went undefeated and tied or set 7 World Records outdoors and had another pair indoors.

Her finest day came in Portland in June when she ran the first 10-flat for 100y and also broke the 220y record with a 22.7.

1971 — The Dashing Dr. Meriwether

In the fall of ’70, T&FN carried a story that would undoubtedly have been considered apocryphal had it not carried Bob Hersh’s byline. In it, he told the tale of a 27-year-old MD who had decided to try running for the first time in his life. Using a technique book by Jim Dunaway as his guide, he worked out for a few months, then ran his first competitive race: 9.6 for 100y. By the end of the summer he had run 9.4 and 21.1y.

In 1971 Dr. Delano Meriwether became a national-class sprinter, wowing fans indoors and making the cover of Sports Illustrated. But it was at the outdoor nationals he made his biggest splash, equaling the fastest 100y ever run with his wind-aided 9.0. But that’s where the fairy tale peaked, as ongoing hamstring problems (and professional concerns) kept him from being a major factor again.

1972 — The Cat In The Hat

A recent discussion on the Internet regarding the most impressive track performance people had ever seen turned up an amazing number of votes for Dave Wottle’s 800 win at the Olympics, even among those for whom Munich was perhaps the first track memory. You know, the guy in the white golf cap.

With 200m to go, the pack was tightly bunched, but Wottle had seven men to pass, obviously an impossible task. But wait! As they went around the final curve, the Bowling Green senior-to-be started picking off world-class runners as if he were in an all-comers meet. As they approached the line, the American still trailed favored Yevgeniy Arzhanov, and it was only a superior lean that got him the win. It was only the second time anyone had won an Olympic 800 title with a faster second 400 (and has happened only once more since).

Wottle was so flushed with victory that he forgot to remove the cap during the victory ceremony, but no less a figure than Vice President Spiro Agnew cabled, “Hat on or off, you are still an American to be proud of.”

1973 — Track Turns Professional

As the glow of the Olympics wore off, track athletes realized more and more that they were becoming part of a large money-making machine. A large part, but they weren’t being compensated commensurately. In an era when rogue leagues were popping up in all kinds of sports, plans for a professional track league finally came to fruition with the formation of the International Track Association (ITA).

A significant number of the sport’s biggest names, including Jim Ryun, Randy Matson, Lee Evans and Bob Seagren, gave up their amateur standing to dash for cash. The ITA hung on for three seasons, but by ’76 the novelty had worn off. The groundwork had been laid, however, for tracksters to get a fairer share of the loot.

1974—No More False Starts

NCAA coaches said they were going to put the rule in anyway, but after the first round of the 100 at the NCAA Championships, few were ready to argue against the need for a no-false-start rule. In just 7 heats of the 100, no fewer than 18 false starts were charged, eliminating no one, and putting the meet about an hour behind schedule.

1975 — A Legend Dies Young

Just as the public at large can tell you where they were when they found out that JFK died, so it is with track fans. Early in the morning of May 29 phones started ringing all over the country. There would be a pause, then the news was half-whispered, “Pre’s dead.” One of the sport’s brightest stars was gone at 24.

Whether you loved him or hated him-and with Steve Prefontaine nothing came halfway — it was always a joy to qatch him run. As he told Kenny Moore in ’73, “I want a race where it comes down to who’s toughest, who can push himself the farthest into that kind of exhaustion where running is unnatural; where you have to whip yourself to go on.”

1976 — El Caballo Thunders Home

Alberto Juantorena didn’t advance beyond the semifinals of the Munich 400, but by ’74, the rangy Cuban had improved enough to World Rank No. 1. After an injury-riddled ’75 the 44.7 sprinter showed his strength early in the Olympic year with a 1:45.80 over two laps, but claimed he wouldn’t double in Montréal. Juanto changed his mind, though-and became the first man ever to win a Games 4/8 combo.

First, the runner dubbed El Caballo (the horse) by his countrymen romped 1:43.5 for an 800 WR. He then returned four days later to muscle through a 44.26 to capture the 1-lap title. After his demanding schedule, which also included a 44.7 relay leg, Juantorena said, “I’m not Superman. I’m tired.”

1977 — 14 Scholarships, More Foreigners

Controversy over the steady march of foreign athletes into U.S. colleges received more ammo as collegiate coaches fumed at the NCAA’s ruling to limit track grants to 14. “The coach will try to get the best mileage out of his scholarships,” said Clarence Robison of BYU. “So the foreign athlete will be more in demand than ever.”

Said Del Hessel of Western Kentucky, “With the number of grants going down and the number of foreigners going up, fewer young Americans will participate in college track.”

“You can go either for quality or depth,” said Bob Beeten of Idaho State. Depth wins dual meets and conference championships, but just a few good foreign veterans can place a team high in the NCAA.”

Tennessee’s Stan Huntsman said, “Coaches will more and more go for the proven foreign veteran and thus ensure a good return on he investment of a grant.” They were right.

1978 — Rono’s Year

A group of track nuts making friendly wagers shortly before the NCAA meet loudly hooted one of their number for predicting that Henry Rono would run a sub-8:20 in the steeple heats. But the brave one knew well that the Washington Stater already had set a pair of WRs that spring, one in the chase (8:05.4 in a low-key invitational) and another in the 5000 (13:08.4 in an early-April collegiate dual meet).

So Rono did break 8:20 in his heat with an 8:18.63, then the fastest prelim ever, and still faster than anyone but Rono has run in the NCAA meet. That summer in Europe he added WRs in the 3000 (7:32.1) and 10,000 (27:22.5) and was a unanimous AOY choice at year’s end. A battle with alcoholism consumed the Kenyan’s later life, but barely dimmed the brilliance of The Year of Rono.

1979 — The Put That Never Came Down

Michael Carter knew his final shot heave at the Golden West Invitational would be the farewell performance of his high school career. The muscleman from Jefferson High in Dallas wanted to make the most of it — and his remarkably high, arching throw became the stuff of legends. The 12lb (5.44kg) ball thudded to the turf an astounding 81-3½ (24.77) from the circle, a performance some experts call the greatest thing they have ever seen at any level of the sport.

Carter went on to football All-America honors at SMU, as well as three NCAA shot titles outdoors and the ’84 Olympic silver medal, and even a pair of Super Bowl rings in pro football. But nothing beats Carter’s put; those who saw it get a faraway, glazed look in their eyes when recalling that final, towering throw.

1980 — U.S. Athletes Get Carterized

A Soviet invasion of Afghanistan prompted U.S. President Jimmy Carter to make a fateful decision: “Get out of Afghanistan,” he told the Soviets, “or the U.S. will boycott the Moscow Olympics.” The Soviets ignored the threat, but Carter was dead serious — to the point of intimidating officials at the U.S. Olympic Committee. One official said, “Go along with the boycott… or we will destroy the USOC. We’ll take away your tax exemption; we’ll take away your passports.”

Although patriotism was touted as the reasoning, the USOC eventually knuckled under to the threats and American athletes had no choice but to stay at home. A number of other western countries backed the U.S. and also stayed away. Moscow’s Games went on, the competition diluted but the real victims of the ill-advised boycott being the athletes who had no say in the decision which robbed many of their one chance at the Games.

1981 — Memories Of Owens

Even as a high school senior Carl Lewis was a star, gaining long jump World Ranking in ’79. He made the ’80 Olympic-team-that wasn’t, but a year later evoked comparisons with his idol, Jesse Owens. First Lewis won a 100/long jump double at the NCAA meet, the first such duo since Owens in ’36. Then at the U.S. nationals, he repeated the pair, on the same night. First Lewis faced prime LJ rival Larry Myricks and produced the No. 2 leap in history. Next, a startling surge just passed the halfway mark in the 100 carried Lewis to the century title-despite throwing up his arms in triumph some 10m from the line. Just two seasons later, Lewis duplicated Owens’ feat of taking four Olympic golds.

1982 — Slaney At All Distances

When she first emerged nationally in ’72 at age 13, she was known as “Little Mary Decker.” Ten years later Mary Decker Tabb was grown up and among the best women distance runners in the world. She was the best American, leading the U.S. list at every standard distance from the 3000 through the 10,000.

In the process, she set no fewer than 5 American Records: mile (4:18.08), 2000 (5:38.9), 3000 (8:29.71), 5000 (15:08.26) and 10,000 (31:35.3). Her times in the mile, 5000 and 10,000 also rated as WRs. But so tough were the Eastern Bloc athletes at the time that Mary rated only No. 9 in he Athlete Of The Year balloting.

1983 — At Last, A World Champs

Adriaan Paulen was viewed as a villain by many Americans after the Munich Olympics, but say one thing for the former IAAF president, he finally gave the sport its long-needed true World Championships. The inaugural edition, a meet Paulen viewed as “my child,” was held in the Finnish capital of Helsinki. The site of the warmly-remembered ’52 Olympics resulted in another fine show, with packed houses celebrating highlights galore. Always javelin fans, the locals went mad when Tiina Lillak won the spear crown on her last throw.

Paulen had been succeeded by Primo Nebiolo by the time the meet rolled around, but the doors had been opened, and the forward-thinking Italian already had plans in the works for a World Indoor Championships and World Junior Championships.

1984 — Boycotted Again!

T&FN said it would never happen, but the folly of the U.S. boycott of the Moscow Olympics came home to roost as Eastern Bloc nations stayed away from the Los Angeles Games, citing fears for the safety of athletes. Only Romania bucked the trend.

Carl Lewis was the meet’s unquestioned star, duplicating the four-victory haul by Jesse Owens in 1936 with wins in the 100, 200, long jump and 4×1.

Valerie Brisco claimed three titles, at 200, 400 and in the 4×4; Chandra Cheeseborough followed her 400 silver with golds on both relays. Perhaps the most emotional victory went to American Joan Benoit in the inaugural women’s Olympic marathon.

1985 — 100 Sub-4:00s

As the Olympic year came to a close, Steve Scott realized he had 89 sub-4:00 miles to his credit. As he says in his recent biography, The Miler, “I needed a goal, and this was perfect.” He would take dead aim at 100 runs under the popular barrier. But on the other side of the world, Kiwi rival John Walker, at 88, had a similar goal. Scott says he suggested they get to 99, then have a head-to-head in New Zealand for number 100, but Walker rebuffed him.

Scott banged out 7 subs in the indoor campaign, but the aggressive Walker took advantage of the Down Under summer season to score 5 before adding 3 more indoors. Walker then headed back home, and while Scott was stuck at 96, became the first to the century mark. “Eat your heart out,” said Walker.

Wearing number 100 on his chest, Scott got his century at the Jenner meet. He would go on to total a record 136 subs before his career ended.

1986 — JJK’s Finest Moment

Jackie Joyner-Kersee barely missed joining brother Al as a gold medalist at the ’84 Olympics as she fell just 5 points short of the heptathlon title. But two years later, JJK proved untouchable. Unburdened of collegiate demands after her graduation from UCLA, as she said, “I could concentrate on myself, which meant the heptathlon.” First, at the first Goodwill Games in Moscow, Joyner-Kersee boosted the 7-event WR by 102 points to 7148. That included a multis-WR 23-0 (7.01) long jump in her favorite individual event.

Not content, though, JJK added 10 more points to her record just 27 days later at the Olympic Festival in Houston. “I just try to do my best each time out,” understated JJK. Multis competitor Cindy Greiner observed, “Jackie has shown all of us what is possible.”

1987 — Moses Finally Loses

After winning the Montréal Olympic 400H gold, Edwin Moses began to gain an aura of invincibility. He cut his WR at the ’77 U.S. nationals and won the inaugural World Cup before suffering an upset loss to Harald Schmid in Berlin. That would be the American’s last defeat for nearly 10 years. Moses compiled a winning streak of 107 finals, including the ’83 Worlds title, a 47.02 WR post-Helsinki and the ’84 Olympic gold en route.

Then on June 4, 1987, Moses met LA silver winner Danny Harris in Madrid; the pair took the final barrier together but Moses hit it solidly. Harris kicked home to finish 0.13 ahead of Moses and end track’s longest win streak.

“I was in 6th grade when his streak started,” said Harris.

1988 — Flojo From Another Planet

Florence Griffith Joyner was a world-class sprinter long before the ’88 Olympic season, but nothing prepared the sport for Flojo’s fabulous flying at the Olympic Trials. A shocking 10.49 quarterfinal which slashed the 100 WR from 10.76 was made all the more unbelievable by the 0.0 wind reading; then a 10.70 semi and 10.61 final.

Yet, she had just started to amaze. In Seoul Flojo struck 100 gold with 10.54w. In the 200 she set two WRs in one day, flashing 21.56 in her semi, then obliterating that in the final with 21.34. Flojo then sped the second turn for the 4×1 champs and capped her historic meet with a 48.1 anchor of the silver-winning 4×4 which pushed the Soviet Union to a 3:15.18 WR. “I couldn’t have imagined all this in my wildest dreams,” she admitted.

1989 — Record Cross Country String

Pat Porter’s attempt to win a record eighth consecutive U.S. cross country title went swimmingly — literally. The 30-year-old Colorado-based harrier grabbed the lead right from the start of the national race, staged in a torrential downpour in San Francisco. The two-time Olympic 10,000 runner never looked back as he covered the 10.35K in 32:08 to exceed the 7 straight overland wins compiled by Indiana’s Don Lash between ’34 and ’40.

Porter bested the sodden pursuers by 11 seconds and noted, “These were the worst conditions of any of the eight races. I’ve never run in rain this bad.”

1990 — The Wall Comes Down

For almost 30 years, the most visible symbol of communism’s hold on Eastern Europe was the infamous Berlin Wall. On New Year’s Day, 1990, the wall fell. The April ’90 edition of T&FN carried a picture of a joyous Wolfgang Schmidt hammering away at the hated obstacle. The former discus WR holder had fallen into disfavor with East German authorities and ended up as a political prisoner. Now he would represent a united Germany.

Even bigger ramifications were to come with the breakup of the Soviet Union, so that by the time of the ’93 Worlds, nations such as Ukraine, Belarus and Tajikistan would have separate representation.

1991 — The Greatest LJ Duel

Carl Lewis chased Bob Beamon’s legendary long jump WR of 29-2½ (8.90) for more than a decade, but on the night that he finally jumped farther, his effort was wind-aided. And Mike Powell jumped farther still.

Competing on a hyper-fast runway at the World Championships, Powell and Lewis put up the best set of marks in history. Lewis was clearly on a roll, hitting 28-5¾ (8.68), foul, 28-11¾w (8.83), and 29-2¾w (8.91) on his first four attempts. Typically having trouble finding the board, Powell had reached 28-½ (8.54), but was more than a foot behind. But in the fifth round, everything came together for Powell, who sailed a mighty 29-4½ (8.95), finally putting Beamon to rest.

But Lewis — a great comebacker — still had two jumps left. Powell clasped his hands in prayer, barely able to watch. Lewis tried mightily but couldn’t outjump his rival, although he did reach a wind-legal PR of 29-1¼ (8.87) and finished off with 29-0 (8.84).

The pair then hugged in appreciation for the presence of the other. Said Powell, “This was a realization of a dream I’ve had for years.”

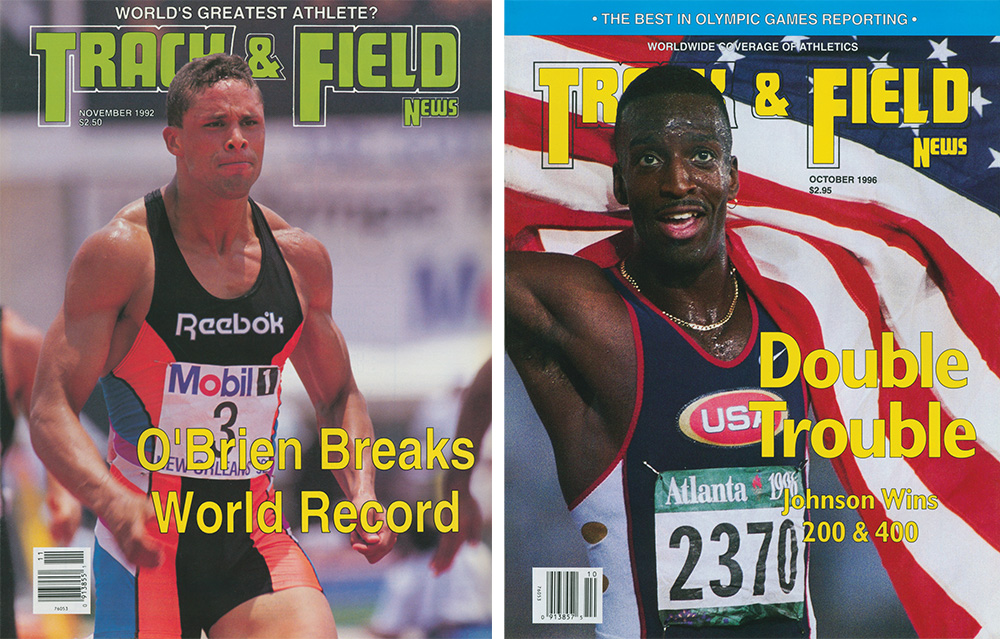

1992 — Dan Or Dave?

Track stars as media heroes? Who’da thunk it? Reebok’s “Dan Or Dave” blitz focused on the anticipated Olympic clash of star decathletes Dan O’Brien and Dave Johnson. “To Be Decided In Barcelona,” the ads concluded. Problem was, O’Brien stunned by not making a vault height at the Trials, thus missing the U.S. team. Johnson overcame a foot stress fracture to capture the bronze, but O’Brien rebounded by totaling a still-standing WR 8891 at the late-season Talence meet.

1993 — Chinese Women Go Berserk

Spectators were left slackjawed in Stuttgart as China’s unheralded women distance runners dominated the World Championships. But that didn’t remotely prepare the world for the orgy of recordsetting they produced a couple of months later at the Chinese National Games. Six different runners set a total of 14 WRs at various distances, with Junxia Wang establishing new standards in the 3000 (8:06.11) and 10,000 (29.31.78), plus a 3:51.92 for 2nd at 1500 to boot.

Enigmatic coach Junren Ma crowded into the spotlight with his claims that the “secrets” of his runners included drinking turtle-blood soup and logging as much as a marathon a day in training.

1994 — The Master Of All Milers

Almost 20 years of singular indoor miling — topped by history’s only undercover sub-3.50 — earned Eamonn Coghlan the title of “Chairman Of The Boards.” In ’93, after three years away from the boards, he decided the world was ready for a 40-year-old to break 4:00. He got close, but it wasn’t until ’94 that he was fully ready.

On February 20, at the unlikely venue of the Massachusetts high school state meet, the 41-year-old Irishman became the first Master to duck under 4:00 with his 3:58.15. “I’ve been trying to do this for two years,” he said, “through a lot of aches, pains and injuries.”

1995 — Edwards Bounces Past 60

Before ’95, Jonathan Edwards had battled the injuries often inherent in the triple jump. But his early-season leaping showed he was healthy: a wind-aided 60-5¾ (18.43), then a World Record 59-0 (17.98). But at the World Championships, he boosted the TJ into the 21st century as he opened with a WR 59-7 (18.16). On his next jump he broke the event’s big barrier with 60-¼ (18.29).

The slim Briton became the third tripler to set a pair of WRs in the same meet-but the first ever to set three records in one season. “So many great athletes have tried for the record and never got it. Then this skinny guy comes along and decimates it,” said Edwards. “It’s almost surreal.”

1996 — MJ Gets His Double

As the decade opened, Michael Johnson emerged as the greatest 200/400 sprinter ever; the first to rank No. 1 in both events. But that kind of doubling caught the schedule makers unprepared. For years he would have to choose which event to run at the major championships, singling at the ’91 Worlds (200 gold), ’92 Olympics (knocked out of the 200 with food poisoning) and ’93 Worlds (400 gold). In ’95 the WC schedule finally accommodated him, and the historic double was his.

But the biggest goal of all, an Olympic double, still remained. It took months of intense lobbying before the timetable was finally altered enough to make it possible, just 4 months before the Games. Johnson proved the decision was a smart one as he took the first gold with a 43.49 lap before producing a run for the ages in the 200, a WR 19.32.

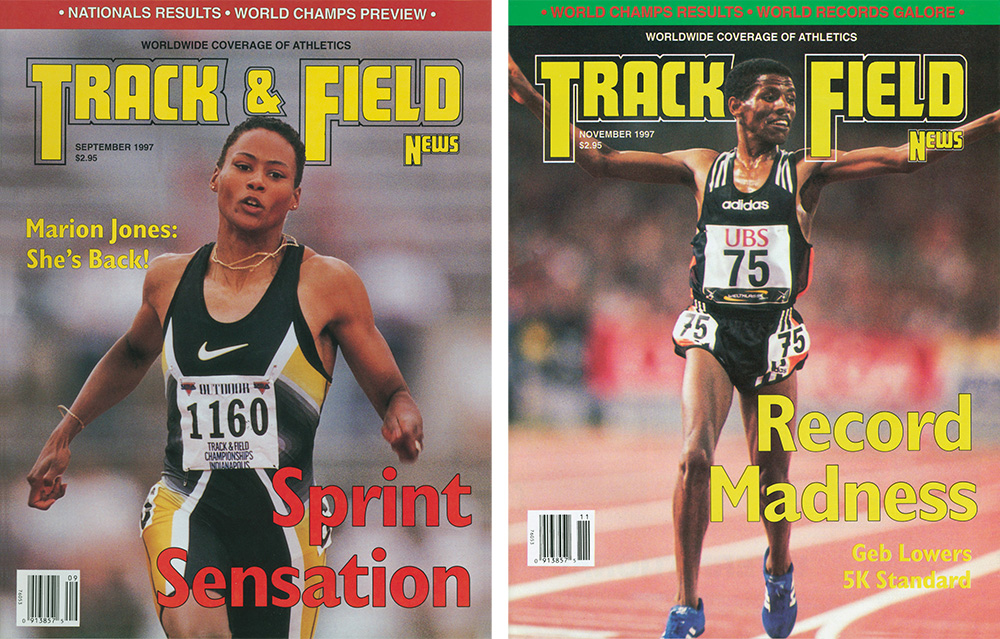

1997 — Preps Rekindle 4:00 Dreams

Sub-4:00 miling by high schoolers was on the verge of becoming common in the mid-’60s, but after Marty Liquori clocked 3:59.8 in ’67 the drought set in. The drought remains, but ’97 nonetheless represented a high point in prep miling.

The stage was set for a huge clash at the National Scholastic meet when Jonathon Riley ran a metric 3:43.18 (worth 4:01.0) and Gabe Jennings turned in a 4:02.81 as the regular season wound down. But neither won the big race, as Sharif Karie (4:02.01) won over Jennings (4:03.27) and Riley (4:05.72) in the best prep mile ever.

1998 — African Distance Wave

African men’s talent kept exploding all-time lists at 800 and above. After high drama throughout ’97, WRs that would stand as the next season began were set at 800 (Wilson Kipketer 1:41.11), the steeple (Bernard Barmasai 7:55.72), 5000 (Komen 12:39.74) and 10,000 (Paul Tergat 26:27.85).

Moroccan Hicham El Guerrouj took the 1500 standard down to 3:26.00, still the WR. In the first two weeks of June, the great Haile Gebrselassie lowered the 5K and 10K standards to 12:39.36 and 26:22.75.

Young American sprinter Maurice Greene made his first AOY top 10 appearance (No. 8), and speedster Marion Jones repeated as women’s No. 1. Jones’ saga, with shining highs and ugly lows, would enthrall and roil for years to come.

1999 — Nebiolo’s Ultimo Anno

After 11 years, Butch Reynolds’ 400 WR fell by 11 hundredths to Michael Johnson and his 43.18 at the World Champs.

Dan O’Brien’s decathlon standard tumbled too. Czech Tomás Dvořák’s 8994 laid the 10-eventer at 9000’s door.

An administrator also made news: Primo Nebiolo, the IAAF president since ’81. In ’98 the gruff Italian had corralled the “Golden 4” Euro invitational meets — Oslo, Zürich, Brussels and Berlin — into a new IAAF circuit of super-elite meets, the Golden League. Seven meetings initially, the series offered a million bucks to be split by athletes who won at all 7; WRs in the meets earned $50,000.

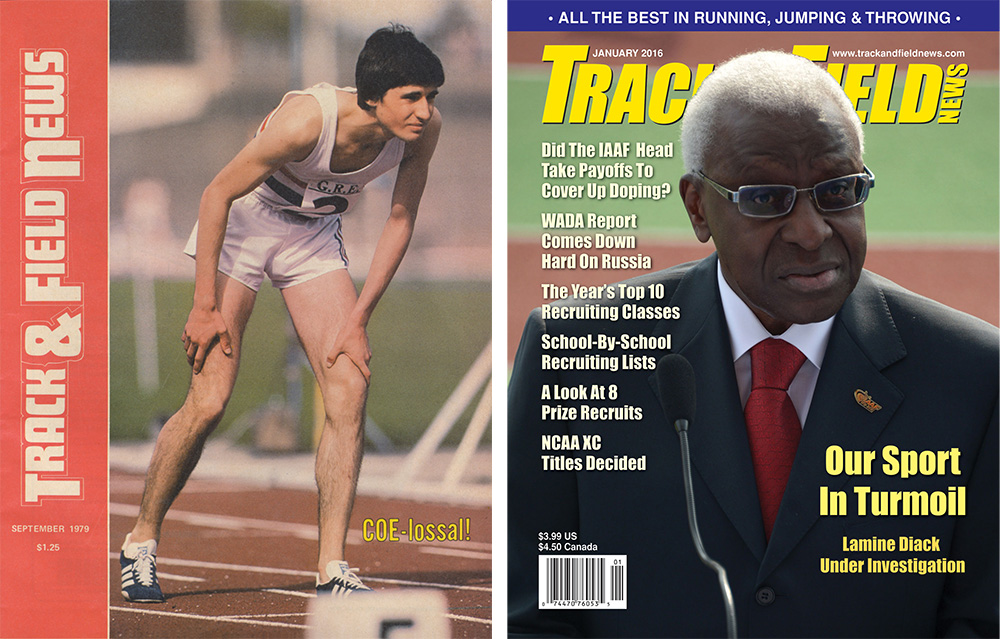

“We want to bring some coherence to the athletics season,” Nebiolo said. But Nebiolo also made news by dying in November. His passing set up the ultimately ill-fated presidency of Lamine Diack.

2000 — Triumph And A Downfall Years Later

The era’s two sprint behemoth WR holders, Greene & Johnson, victorious in the Olympic Trials 100 & 400, strained hamstrings in the 200 final and DNFed, short-circuiting a first-rank Games matchup.

The Down Under Olympics went off fair dinkum anyway. Mo & MJ each won two golds anyway. Aussie torchlighter Cathy Freeman in a hooded speedsuit roared to women’s 400 gold as 112,524 fans let loose at thunderous volume.

And the Olympics staged a woman’s pole vault. The USA’s Stacy Dragila came from behind on the countback as the first queen of an increasingly crowd-pleasing event.

Sprinter/long jumper Jones carried home a record 5-medal haul for the modern event slate under a cloud. Her husband, putter C.J. Hunter, missed Sydney after 4 positive doping tests. The scandal built over years with horrific stock elements: cheating, lying under oath, prison and eventually the stripping of Jones’ medals and all her results from Sydney onwards.

2001 — Webb Unseats Ryun

Suddenly in January came Alan Webb. We reported that, “Just as T&FN’s editorial staff was debating how best to preview — without pressure-cooking — the coming season of high expectations for Webb and fellow distance standouts Dathan Ritzenhein and Ryan Hall, Webb ended everyone’s wait,” With a 3:59.86 clocking at NYC’s Armory, the Virginia senior made himself the first sub-4 prep since Liquori and the first to do it indoors.

By the time Webb made his second cover of the season, on the August issue, that front page could declare in massive bold type, “Ryun’s Records Gone — Webb Miles 3:53.43.”

Webb shattered Ryun’s absolute HSR, 3:55.3 in a run for 5th against pros at the Pre Classic in May. The race winner, scoring the first sub-3:50 on U.S. soil? None other than WR holder El Guerrouj.

2002 — Calm Before Calamity

In hindsight, particularly versus events that would break in ’03, ’02 was a calm year.

In the indoor season a rival to WR holder Dragila rose up in the vault. Diminutive Svetlana Feofanova of Russia, 2½ inches shorter at 5-4¼ (1.63) than the American vaulter, had competed well at the Edmonton Worlds where Dragila won and both cleared 15-7 (4.75). Feofanova had moved to No. 2 on the all-time list.

Over 8 days in February, though, the Russian raised the WIR 3 times adding a centimeter each time to reach 15-6¼ (4.73).

At their last undercover meeting of the season in Birmingham, Feofanova won, Dragila placed 5th, and 3rd was a younger Russian named Yelena Isinbaeva. Feofanova won the Euro Indoor title with yet another WIR, 15-7 (4.75) and scaled 15-8¼ (4.78) outdoors.

2003 — Best Of Times, Also Worst

Great days in the sport? Briton Paula Radcliffe smashed her women’s marathon WR all the way down to 2:15:25. Tergat took the men’s standard through a minute barrier to 2:04:55.

Future legend sprint faces appeared. Our September cover’s headline read, “The Next Great Long Sprinter? — Teenage Sensation Usain Bolt.” Our November issue’s poster insert (a cool concept in the hard copy era) featured our Girls High School Athlete Of The Year, a sensation named Allyson Felix.

The Worlds in Paris were terrific. Record fourth titles for El Guerrouj and 110 hurdler Allen Johnson stood out.

The men’s distances were red hot. 20-year-old Kenenisa Bekele closed his meet record 26:49.57 10K in 12:57.24 to pip Gebrselassie by 1.2, then came back for 5K bronze behind a teen MR-setter by the name of… Eliud Kipchoge. With El G 2nd, what a race!

Good, bad or middlin’ day in the sport? Regionals debuted for the NCAA. Approval rating two decades later: it is what it is?

Worm can-opening moment of the year and decade? Kelli White’s 100/200 double gold minute at the WC followed by her positive test for a banned narcolepsy drug, Modafinil. The dark underbelly scandal we’d all later shorthand as BALCO was off to the races.

2004 — Shots In The Olympic Birthplace

“There will never be another shot put like this one,” wrote correspondent Jack Pfeifer. “In an inspired gesture to Greece’s unique place in Olympic history, the organizers moved the putting competitions to the grounds of Olympia,” Peloponnesian birthplace of the Games 3 millennia ago.

As thrilled and chilled as the lucky few spectators felt, Adam Nelson, the men’s silver medalist in Sydney 4 years earlier, found grounds for other shifting emotions over many ensuing years.

In the first OG field comp settled by a secondary mark, Nelson threw 69-5¼ (21.16) out the gate and then fouled his next 5 as Yuriy Bilonoh equaled Nelson’s leader on his last put to take gold via next-best distance.

Eight years later retroactive testing revealed the Ukrainian had doped his way to gold. Nine years later, Nelson finally got the medal he had earned.

Athens was a Games rife with thrills and chills, and also one where no fewer than 8 gold medalists later received doping bans — grim trademark of the era across many sports.

2005 — Post-Olympic Guard Change

Winners of the ’04 AOY honors had been Bekele and Isinbaeva — a two-athlete sea change, as each would be voted Athlete Of The Decade in 6 years’ time.

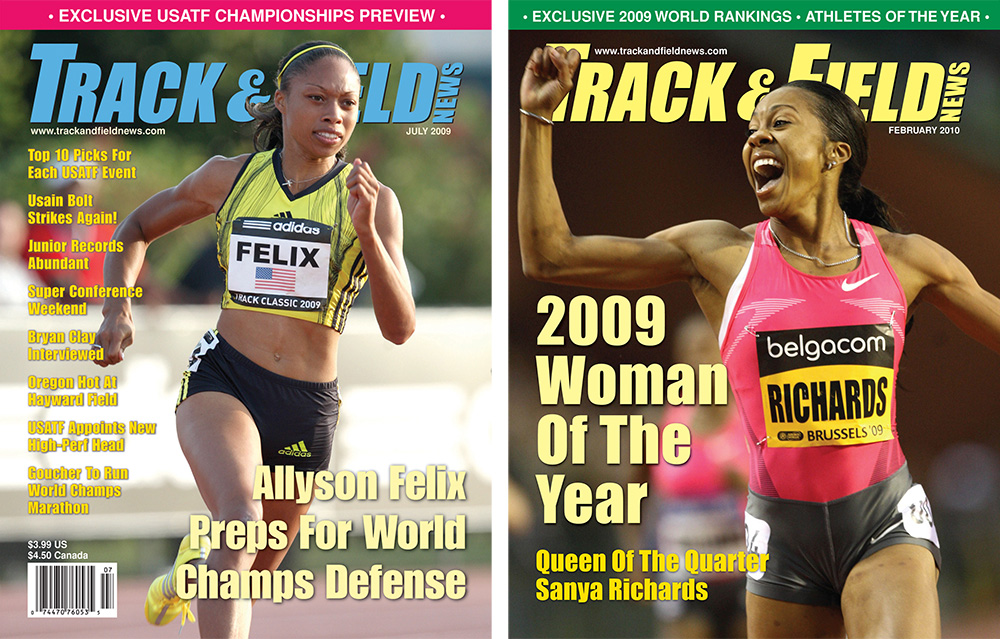

When the future AOD pair repeated as AOYs in ’05, other names whose impact would be lasting joined the frontline cast in Top 10 voting for the first time: Justin Gatlin, Allyson Felix & Sanya Richards (no Ross in her name yet). Gatlin won the WC sprint double in Helsinki, Felix a 200 gold and Richards 400 silver.

World and Olympic medals would accrue to each for years to come. SRR finished her career as the 400’s No. 2 in all-time World Rankings points. Felix scored her way to No. 3 at 200 and No. 4 on points in the lap.

Gatlin’s arc bestowed upon him the unofficial love-or-hate-the-guy leadership of the millennium’s first two decades by the time he earned his last global medal at 37.

2006 — Kastor Busts A Barrier

Even before ’04 — when Deena Kastor’s bronze run from Marathon to Athens made her the second U.S. woman 26-miler OG medalist — the training enclave in which she and Meb Keflezighi were the first breakout stars had led a U.S. distance revolution.

In April Kastor made history with a London Marathon win. She crossed the line in 2:19:36. History’s fourth sub-2:20 woman to that date, Kastor also reached her career Rankings zenith rating No. 1.

An April issue T&FN feature profiled other members of the Team Running USA group guided by coaches Bob Larsen and Terrence Mahon living at the time in a house in forested Woodside, California. Kastor was in Mammoth, the team’s main base, but the runners connected with that house represented a snapshot of leaders on the U.S. distance scene in the era: including Ryan and Sara Hall, Jen Rhines, Ian Dobson, Ryan Shay (whose later demise during the ’08 OT Marathon wrought shock and grief), Lauren Fleshman and one-of-a-kind miler Gabe Jennings.

Taped to Jennings’ bedroom door was the T&FN January internal cover depicting ’05 AOY Isinbaeva.

2007 — Two Yanks At The Top

Not since Carl Lewis and Edwin Moses in ’83 had a pair of U.S. athletes topped the men’s AOY vote tally. Tyson Gay and Jeremy Wariner ended that state of affairs.

Several dashmen had earned recent T&FN covers and Justin Gatlin was off the scene doping-DQed. These speedsters included Asafa Powell, Xavier Carter, Walter Dix and Wallace Spearmon. Gay, though, crowned himself the new sprint king at the WC in Osaka with a 100/200 double and relay gold. His deuce mark, 19.76, was a meet record and left a noted Jamaican, Usain Bolt, the silver.

Wariner led a U.S. 400 sweep and 4×4 victory, major golds 3 and 4 in the Texan’s career.

Another American doubled, as well. Athens 1500 silver medalist for Kenya Bernard Lagat had quietly become a U.S. citizen that year. Now eligible to represent his new country, he conquered the 1500’s defending champ and Kipchoge to win the 5000, first U.S. to claim either title.

Webb had his career year on the clock, lowering the mile AR to 3:46.91 yet placed just 8th in the Osaka final.

2010 — Diamonds Replace Gold

Per our reportage, “The IAAF’s Golden League, which began life as the Grand Prix Circuit in ’85, breathed its last in September of ’09, to be replaced this year by an ambitious new venture,” a 14-meet Diamond League.

With an expanded meet slate, the DL has carried the torch since as WA’s premier series.

“We don’t know when or where yet,” T&FN further reported, “but fans are guaranteed ‘multiple’ meetings between Bolt and Gay, with Powell thrown in for good measure. That can only be good for the sport.”

As it turned out, Gay sprinted undefeated in DL 100s on the year, dealing Bolt a rare loss in Stockholm. Powell raced each of the other two once. No DL lined up the trio together.

Collegiately, the 4-meet NCAA Regionals morphed into a 2-meet “championships first round” — with no team scoring, no finals, no winners.

2011 — False Start Rule Jolts Bolt

There was some “sky is falling!” sentiment in ’10 when the IAAF and USATF adopted the one-and-you’re-done false start policy found in the prep and collegiate rules for decades.

“For me, I have no problem; I never false-started yet,” Usain Bolt said. “It will be better for the sport. It will be a problem for some people but not for me.”

Not so at the World Champs. Ironically, the Jamaican superstar false-started in the 100 in Daegu. He tore off his singlet in the moment but told the one reporter who found him afterwards, “Looking for tears? Not going to happen.”

Rather than sob, Bolt went on to win the 200 in 19.40, the No. 4 all-time performance, and anchored another Jamaican 4×1 WR (37.04).

Team USA sparkled in Korea: Dwight Phillips broke from outside T&FN’s top-10 picks to claim his fourth long jump gold. Lashinda Demus triumphed with an AR in the 400 hurdles after 7 years of trying. Jenny Simpson, Matt Centrowitz, Christian Taylor, Will Claye and Ashton Eaton medaled, part of a rising U.S. generation.

2012 — Ashton Eaton All-Conquering

“For most fans the one defining moment of London 2012 was David Rudisha’s new standard in the 800,” 1:40.91, no rabbits. A feature in our pages got that right. Bolt was electric again. Mo Farah’s distance double delighted the super-fan locals and Team USA came up just one medal short of the “Project 30” goal set by previous USATF CEO Doug Logan.

But the year also belonged to decathlete Ashton Eaton, who ran, jumped and threw through rain and cold to a WR at the Olympic Trials. He then won gold in London with teammate Trey Hardee 2nd.

Eaton as World’s Greatest Athlete balanced his slimmer bank account versus Bolt’s with plain old love of the sport. “I don’t really do this for any of that stuff,” he said. “I really don’t care about riches and all those other things. It’s very cool to have it, it’s good for sports promotion because this has clearly changed my life… But, like I said, before: I don’t care. I just like doing what I’m doing.”

2013 — Cain You Believe It?

“There were the 6(!) High School Records indoors and out, spanning the 800 to the 5000, but above and beyond that the racing savvy — a USATF Indoor mile title, followed by 2nd in the Outdoor 1500, and a run to the final of the World Championships.”

That’s how our feature on High School Girls AOY Mary Cain (Bronxville, New York) distilled a phenomenal season.

17-year-old junior Cain accelerated that far into the sport’s fast lane as an athlete in coach Alberto Salazar’s high-powered Nike Oregon Project before she even learned how to drive a car on her own.

Cain’s rapid progress followed by burnout shone light on troubling corners of the elite sport, including Salazar’s ethically questionable methods and weight-shaming, that still reverberate today.

2014 — A Second 20-Foot Man

It had been 21 years since pole vault superman Sergey Bubka — history’s only 20-footer throughout the intervening seasons — set the highest of his 35 World Records, 20-2 (6.15) indoors in his hometown of Donets’k, Ukraine.

Fittingly, Bubka organized the Pole Vault Stars meeting in that same hall at which Renaud Lavillenie at last soared higher — to 20-2½ (6.16). After needing two tries earlier in the comp at 19-8 ½ (6.01), the 27-year-old Frenchman vaulted over the record setting on first attempt. Pushing his luck, Lavillenie had the bar raised to 20-4½ (6.21) and again took a WR shot.

Unlucky move, that proved to be, as he clipped the edge of the raised runway, which opened a 4-inch gash in his heel. He finished the day ecstatic, nonetheless: “I will need time to get back down on Earth. It was a mythical record.”

2015 — Changes In Corridors Of Power

On-field feats, of course, stirred the blood in the Beijing World Champs year — Bolt and Farah double defenses, the third in Eaton’s eventual string of 4 OG/WC golds, Allyson Felix adding a 400 gold to the 8 she already had in the 200 and relays — yet “suits” were also scoring wins.

USATF CEO Max Siegel used the December ’14 Annual Meeting to celebrate bumping up finances. He announced a 58% spending boost from $19-million in ’11 before his hiring to $30 million in ’15 facilitated by 9 new partnership deals. Siegel’s biggest score, a Nike sponsorship inked in ’14, promised about $20 million in annual revenue over 23 years.

Internationally, British middle distance legend and former CEO of the London Olympics Seb Coe was elected IAAF (now WA) President.

“There is no task in my life for which I have been better prepared,” Coe said — not yet realizing a vast corruption and pay-to-look-the-other-way Russian doping scandal involving his predecessor Lamine Diack would soon erupt.

2016 — Athletes Outshined Crooks

“Drugs, sports, politics and subterfuge. Are any more ingredients needed for a scandal that has shaken sport — particularly track — to its very foundation?”

Thus began a September issue rundown of recent developments in the Russian doping scandal under the headline “Track’s Version Of War & Peace Drags On.”

Thankfully, athletes brought reasons to smile.

A few of the cool happenings:

• Vashti Cunningham skyed over an HSR 6-6¼ (1.99) to win the USATF Indoor before taking World Indoor gold in Portland — yet another prep recordsetter, Olympian Sydney McLaughlin, topped her in HS AOY voting!

• Keni Harrison fought back after her Olympic Trials 6th and in her next meet clipped a hundredth from a 100H WR that had stood for 28 years.

• Wayde van Niekerk demolished Michael Johnson’s hallowed 400 standard with his 43.03 Olympic triumph.

• Also in Rio, Americans made Games history: Matthew Centrowitz first U.S. 1500 gold medalist since 1904; Ryan Crouser (Olympic Record) & Joe Kovacs first U.S. shot 1-2 in 20 years; Michelle Carter (American Record) first U.S. women’s shot winner ever.

2017 — A Season Of Change

The first news up in a season that reset expectations for the future was Eaton’s retirement announcement in January. Norms were reset throughout the year.

Bolt’s glorious string at last played out, as Americans Christian Coleman and Gatlin relegated him to bronze in the WC 100 in London and the Jamaican’s relay leg added a hamstring strain to Bolt’s insult.

U.S. distance fans rejoiced at Emma Coburn’s gold medal in London. The victory elevated her into a steeple champ’s club heretofore populated entirely with African stars and athletes later banned for doping.

2018 — Youngsters Light It Up

An “off year” without an Olympics or Worlds in several respects was anything but. And this one, of course, had a World Indoor Champs in which 60 WR-setter Coleman claimed that title, Harrison scored 60H gold and Sandi Morris succeeded Jenn Suhr as global PV titlist.

Following on Shalane Flanagan’s first-in-40-years U.S. women’s New York marathon victory in ’17, Desiree Linden claimed the first Boston title by a U.S. woman in 33 years.

Our April cover headline shouted, “What A Month For Syd The Kid,” McLaughlin. May’s cover, “Ryan Crouser Ripping The Shot.” June’s, “Michael Norman Runs 43.61.”

Norman’s USC teammate Rai Benjamin — Antiguan but U.S. born and raised and soon to have Team USA eligibility — equaled all-worlder Edwin Moses’ PR, 47.02, in the NCAA 400H.

Frenchman Kevin Mayer crushed Eaton’s deca WR. Kipchoge, now a marathoner, was men’s AOY.

Caster Semenya earned our Woman Of The Year vote, scoring Rankings spots at 400, 800 & 1500 — events from which a coming WA ruling on DSD athletes would bar her participation the next year.

2019–2020 — Nothing We’d Ever Seen Before

What can one say about a Worlds in Doha’s air-conditioned outdoor stadium, followed by a devastating pandemic?

400 hurdler Dalilah Muhammad had run down Yuliya Pechonkina’s WR of ’03 by 0.14 with 52.20 at the USATF Champs but came to Doha down 2–1 to McLaughlin on the year. Their race was epic. Muhammad’s 52.16 lowered her WR by 0.04 and McLaughlin’s 52.23 closing fast was the No. 3 performance ever, trailing only Muhammad’s WRs.

The men’s shot played out as the event’s greatest comp ever, Joe Kovacs winning in the last round at 75-2 (22.91), equal-second longest all-time over Crouser and Walsh, both a centimeter back at 75-1¾ (22.90). With the 75-foot barrier battered, 7 men cracked 70ft (21.34) in the same meet for the first time ever.

Six days after the WC finished, in a paced and meticulously organized run in Vienna Kipchoge covered the marathon distance in under 2 hours, 1:59:41. Not an actual race but what was once thought impossible accomplished.

The Nike-sponsored Kenyan’s feat raised public awareness that “super shoes” were out there. While the coming technological disruption was nothing next to the impending pandemic, it would soon rewrite all-time lists for running and jumping.

For Louisianan/Swede Mondo Duplantis — a 3-time T&FN cover subject in ’17 and ’18 — ’20 was not a lost year. Twice in February, he raised the absolute PV WR, to 20-2¾ (6.17) then 20-3¼ (6.18). In September in a Rome arena essentially devoid of spectators he erased Bubka’s 26-years-extant outdoor WR with a 20-2 (6.15) clearance.

2021 — Empty-Stadium Games

Tokyo’s Olympic stadium —under a COVID spectator ban — was downright hermetically sealed though exposed to August weather.

200 world champion Noah Lyles assessed, “I don’t think you understand how lifeless it was… to have no crowd there. It was dead silent.”

Discus winner Valarie Allman, who launched the longest Olympic final cast in 33 years, felt unperturbed. Grant Fisher, 5th in the 10K, said it “was a little weird, but once you started racing, you kind of shut all that stuff out anyway, and it just felt like a normal race.”

Neither 400H race was normal. Two-time men’s world champ Karsten Warholm staggered his rivals with a 45.94 WR. The otherworldly time crushed his 46.70 record from earlier in ’21 as Benjamin and Alison dos Santos too ran under Kevin Young’s pre-Warholm standard.

Muhammad had a response to McLaughlin’s gobsmacking WR at the U.S. Trials, 51.90, yet Syd the no-longer Kid covered. With 51.46! Femke Bol, a Dutch 21-year-old, finished in 52.03 as No. 3 all-time.

Crouser repeated as gold medalist, untouchable. At the Trials he had spun his shot nearly a foot beyond the old WR to 76-8¼ (23.37).

A relieved and exhausted Felix won medals 10 and 11 to become the most decorated female track Olympian of all time.

2022 — World Champs XVIII Stateside

After nearly 4 decades of outdoor World Championships, the U.S. finally hosted one, in Eugene, Oregon, the nation’s track-&-fieldiest town, love it or hate it.

Jeff Hollobaugh’s analysis found the event’s essence: “From the sublime magnificence of McLaughlin destroying her own 400H standard with a barrier-busting 50.68 (perhaps expected, but that fast?) to the stunning shock of Tobi Amusan’s 12.12 best over the sprint hurdles that had even some experts doubting the timing until she came up with a wind-aided 12.06 in the final, to Mondo Duplantis’s 20-4½ (6.21) vault as the meet’s exclamation mark, fans could only shake their heads in amazement.”

Competing in a new state-of-the-art stadium the home team delivered “3 men’s medal sweeps (100, 200, shot) and what has been heralded as a record total 33 medals.” 3 better than East Germany ’87 in Rome.

Sticklers, that we at T&FN are, we had to asterisk that stat: “This year’s total includes 6 medals from 4 events that weren’t even on the books in Rome — the mixed relay and the women’s pole vault, triple jump & hammer.” ◻︎