FEBRUARY HAS DELIVERED tragedy and emotional trial for the sport and distance power nation Kenya. A second painful blow landed on the 15th of the month, 4 days after the passing of marathon WR holder Kelvin Kiptum, when reports came out of Nairobi that Washington State legend Henry Rono — he of 4 World Records within 81 days in 1978 — had succumbed at age 72 to an unspecified illness.

Deprived by Kenyan boycotts of the ’76 and ’80 Games of chances to perform for the world on the Olympic stage — and with his brief run of prime years preceding the first World Championships in ’83 — the sense is we never saw what a talent of Rono’s immense stature might have produced in an openly pro track world like today’s.

To honor Rono’s memory and spectacular ahead-of-the-curve performances, following you will find our 25th anniversary look-back at the distance great’s astounding ’78 campaign. It ran in the April 2003, edition.

Rono’s two sessions as a T&FN Interview subject are linked here.

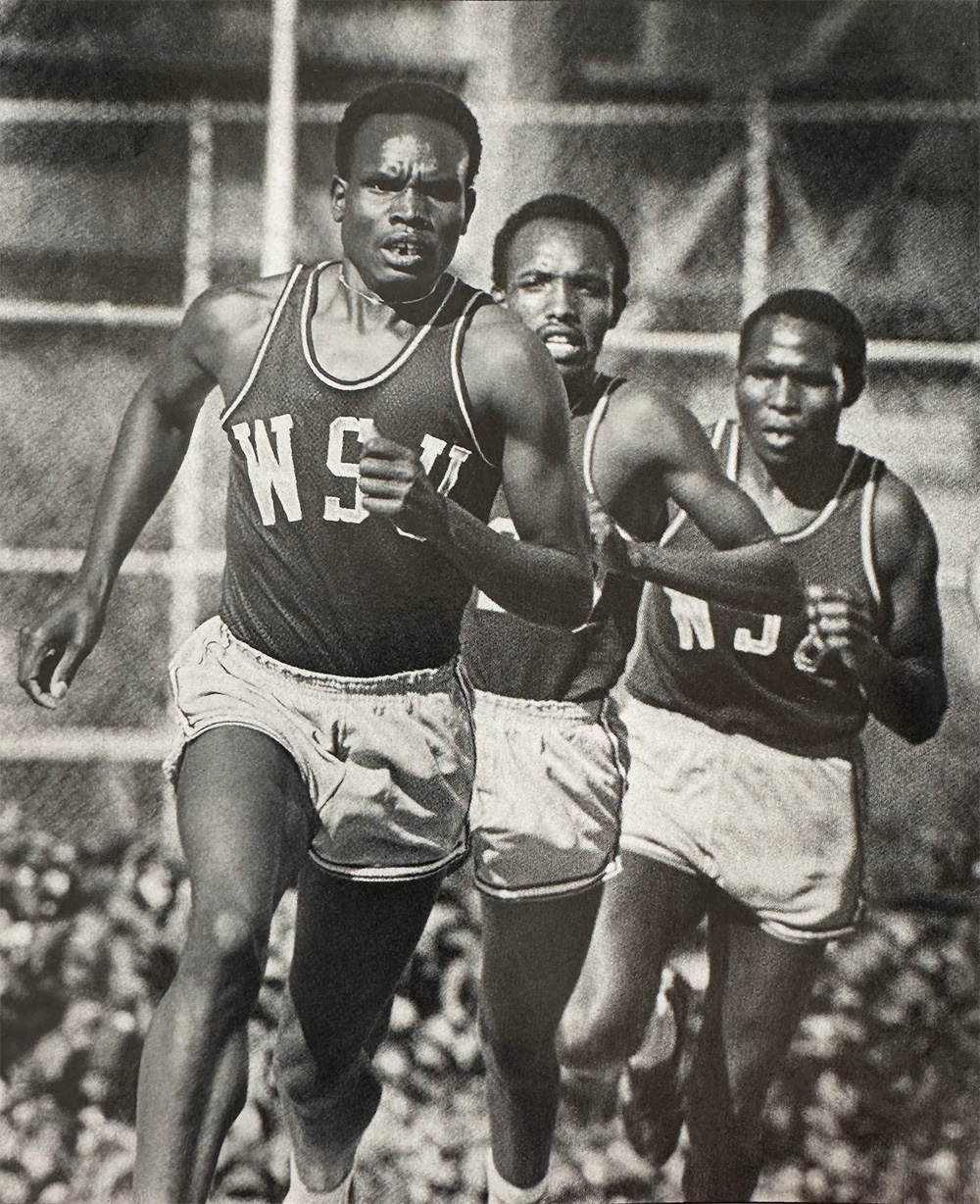

TWENTY-FIVE YEARS AGO Washington State sophomore Henry Rono began one of the greatest World Record streaks in history, blowing the collective mind of the distance running world.

In a span of 81 days (see box), the gap-toothed Kenyan star reeled off WRs in the 5000 (13:08.4), steeple (8:05.4), 10,000 (27:22.4) and 3000 (7:32.1).

He ran the 3K before a full house at the Bislett Games in Oslo, Norway, but mere handfuls of fans witnessed the shocking 5K in Berkeley and the steeple shot his coach John Chaplin had predicted for a rainy day in Seattle.

Even the 10K record, in Vienna, Austria, fell before a relatively tiny group of about 500 who lingered after a soccer match.

But with Kenyan boycotts robbing Rono of Olympic opportunities in ‘76 and ‘80, the world basically missed seeing him run. “I thought the Olympics were all politics,” Rono wrote recently in the East African Standard, and only he knows if the disappointment helped spiral him into the alcoholism he subsequently developed.

Rono’s greatness only reemerged in brief flashes thereafter. He set a second 5K record (13:06.20) in ‘81, and fans still rave about his 15lb-overweight defeat of Alberto Salazar in a brilliant 10K in ‘82.

“All in all, it was the most incredible race I ever ran in my life,” said Rono, who in his peak racing days packed 139lb on his barrel-chested 5-7 frame.

After the tragic death of a son in ‘85, Rono tried a comeback on the roads. It never really took hold, and Rono sadly weathered an arrest for bank robbery in a case of mistaken identity and further decline into drinking before pulling himself off the bottle in the last 5 years.

Today he works part-time as a teacher and coach in New Mexico as he pursues a Masters in Education.

One hopes Rono is at peace with his achievements of a quarter-century ago. He no longer speaks with Chaplin, and declined an interview with T&FN in a brief-but-poignant e-mail:

“These questions have been answered a long time ago, so I’m moving forward for other things to write about. Unfortunately I cannot do business with you. I am sorry.

“Thanks yrs friendly. “Henry”

So we went to Chaplin for the tale of ‘78 and the 24-year-old Kenyan who had first come to Washington State in the fall of ‘76 after being denied the chance to run in the Montréal steeplechase.

“In the fall [of ‘77] after he was beating up Samson Kimobwa, who was the World Record holder in the 10K,” Chaplin says, “I’m not that smart, but I said, ‘You know, you could be the first person to break all three records [steeple, 5K, 10K].’ And Henry looked at me and didn’t say a word.” (Continued below)

The rest of the world remained clueless to those goals, particularly as a case of the flu rendered Rono unspectacular at the NCAA Indoor, but a tiny group at a meet in Spokane on April Fool’s Day got a preview when he ran 13:22.7 for 5000 in a snowstorm.

Derek Bridges, an Idaho frosh in the race at the time, remembers, “Rono went out in the middle of our pack at the first lap in slightly over 70 seconds. Then I’ll never forget when he said, ‘Excuse me, excuse me,’ and we gave him a little gap of space, when BAM! He shot out like a cannon. In one turn he put a gap of over 50m on us and kept rolling. Someone was out ahead rabbiting for him, and he shot out and caught up, passed him and still ran that first mile in something like 4:16 or 17 — and just kept going. Mind you, no one warmed up for that race. The Kenyans were playing soccer and kick ball in the gym. I get cold just thinking about it.”

The Wazzu–Cal–Arizona State triangular came a week later on a sunny mid-’70s afternoon. Chaplin recalls, “I said to the team, ‘Henry’s got a real shot here, but to do that I’ve got to pull him from the mile. You guys have got to come through and win the relay and the hurdles and a few other things.’

“So everybody pitched in. We put him with Samson and Josh Kimeto, and Samson took the first 1500 and Joshua took the next 1500, and by that time the guys from Arizona State were simply all around the track. He simply ran them down, one by one by one.”

The first lap had been a 67, but when the next two went in 63 and 64, veteran announcer Bob Steiner alerted his audience that something was up.

“I don’t know why I did it,” he told T&FN at the time. “I’ve never called a World Record after 3 laps. And I’ve seen those Kenyans set super paces before then float in when the race was under control.”

This time, though, Rono laid down a 61 before the mile and then 62-64s before unfurling a 59.4 to close. Dick Quax’s WR was gone, with 4.5 seconds to spare. Memories fade but Cal alum Karl Uebel believes he remembers walking out onto nearby Sproul Plaza, a magnet for street musicians, to see a jubilant Rono beating the skins of a borrowed bongo set.

Chaplin says, “Then we went to the steeplechase and we ran in Eugene a week later. Henry said, ‘What’s the stadium record?’ I said, ‘Well, it’s 8:21 or something by Munyala and Marsh, but I don’t want you running much faster than that because the [steeple pit’s] illegal here.’

“So I’m walking around and I look down and, son of a bitch, he was running right around 8:10. I got pissed. I threw my rain jersey and said, ‘Goddammit, run an 80,’ and he did. He ran 8:14 or whatever it was for the record and the fans were just pissed.

“I said to them, ‘Your fans don’t deserve a World Record because this reporter, Carl Cluff from the Portland Oregonian, had asked me, ‘Can the kid read or write?’

“So then I didn’t shut up while I’m ahead and I said, ‘And besides, we’re going to break it in the state of Washington,’ and I gave them the date.”

The date Chaplin gave was May 13, the site an invitational in Seattle. It hailed early in the day and the thermometer read 55 when Rono stepped to the line. Chaplin believes the steeple’s finishline location on the backstretch confused a few people that day.

“There were more reporters there to get me than anything else,” he says, “and the stupid announcer said he’s not going to make it. I about broke my neck; I was about 20 rows up and I said, ‘You’re fine, you’re fine!’ And he sped it back up and hit the barrier over the water with his instep.

“Henry ran 8:05, and he said, ‘Coach said we had to do it; I guess we had to do it.’ I thought, ‘Thank you, thank you, Great Track Man,’ and I never pulled that [called shot] stunt again.”

Rono finished the collegiate season by boggling the minds of NCAA spectators in Eugene with an 8:18.63/13:21.79 double about four hours apart-in the heats. The memory of the 5K still moves those who saw it to marvel (see box). Running it like a solo “straights-and-turns” workout, Rono’s pace was wild, starting with a 65, then following up with a 61 and a 59. He ran as slow as a 70 for lap 7, then tossed in a 61 on 12.

“After the steeple,” Chaplin says, “he came to me and said, ‘What was the record that Prefontaine made here on the track?’ And I told him. That was all he said.

“We had talked about how years ago Arne Kvalheim had run against Lindgren and Lindgren had jogged the corners and sprinted the straightaways and drilled his ass to the tree, beat a very good Oregon runner doing that. He kind of put the two together in his mind, I think, and decided he was going to show these sons of bitches, this Carl Cluff.”

Nursing a sore foot, Rono hammered out an 8:12.39 steeple win and then opted out of the 5K, won by Oregon’s Rudy Chapa.

Eight days later he ran the 10K WR in Vienna. Jos Hermens — a world-class runner then and now the manager of today’s recordholder, Haile Gebrselassie — set the pace for the first 4km in a meet Chaplin set up for the record attempt.

“I think he could have run faster,” Hermens says of Rono’s 5-second lowering of Kimobwa’s standard. “He was just phenomenal. It was just one of those races where people look like they have unlimited potential.” Rono sprinted his last lap in 57.2 to win by more than half a minute. (Continued below)

Sixteen days later, after an intervening double in Kenya to qualify for the World Cup, Rono set his 3K record before 13,000 fans in Oslo — 59.0 seventh lap, 28.6 final 200. “I wasn’t even necessarily trying to win,” he said. “Only to do my best. American runners think too much and are preoccupied with others.”

Yet Rono rose to his records in the American collegiate system, with its heavy dual-meet orientation of the time.

“The difference here was 1. the environment’s conducive because Pullman is a small town,” Chaplin says.

“2. they had regular training; regular is the operating word here. We ran 5 x 1000; we never ran anything faster; we started with 3, we went to 5. We closed up the time and took the interval from 3 to 2 minutes. We tended to undertrain rather than overtrain.”

Says Hermens, “I think he had the same potential as people like Haile. Haile could never break the record in the 3000 steeple. Rono had maybe a little less speed. He didn’t have a great, great, great kick, but he didn’t even need it; he was killing everybody.”

Yet Hermens is saddened by the way Rono foundered in his post-collegiate career. “I think Rono had all the potential to be around for 10 years or more, no doubt,” he says, “if somebody would have really cared about him.

“OK, he was not easy to approach and I think he mistrusted a lot of people, but I don’t know if that’s because of what happened before or why exactly.”

Both Chaplin and Hermens agree Rono would have been better served to spend more time in Kenya in the following years.

“Why was he drinking?” Hermens asks. “It also has to do with African athletes when they lose their roots and are too far away from home.”

How should Rono be rated against those who came after and ran faster? “I don’t think there’s any comparison,” Chaplin says. “First of all, you have to compare a guy in his own era, when he dominates. You can’t compare them later because of a lot of factors. He was very young when he basically quit.

“Could he have run faster? Sure, but somebody had to be there. Most of these guys are running races where they have two and three rabbits. He ran those races cold in a dual-meet system.” ◻︎