IF ASKED what was the single greatest day of track & field to have taken place on American soil, many a pundit would immediately cite the 1935 Big 10 Championships (also known at the time as the Western Conference). Said meet was hosted at Michigan’s legendary Ferry Field in Ann Arbor. That May 25 day, of course, was when Jesse “The Buckeye Bullet” Owens set 5 World Records and tied another in the span of 45 minutes.

The Ohio Stater began by tying the 100y WR (9.4) and then set new WRs in the 220 (20.3, also breaking the 200m record), 220 hurdles (22.6, also breaking the 200 record) and most notably, the long jump (26-8¼/8.13). An incredible day in U.S. track & field history, no doubt, but 25 years later, an unheralded competition took place that arguably belongs in the single “greatest day” conversation.

Four weeks after the 2-day ’60 Olympic Trials at Stanford, the U.S. team would participate in a series of three West Coast pre-Olympic meets before shuffling off to New York City for processing en route to the Rome Games. First, they’d compete in Eugene, Oregon (July 30), then in Long Beach, California (August 05), and lastly, a meeting at Mt. San Antonio College in Walnut, California (August 12). So extraordinary was the concluding contest that the Los Angeles Times gushingly proclaimed it “the greatest ever mass assault on the track & field record book.”

Larry Snyder, who, not so coincidentally, had been Owens’ college coach at the time of his ’35 fireworks show, was appointed as the head coach for the ’60 Olympic squad. When gathering the troops for their team meeting just prior to this final training meet, he implored his Olympians to “post marks that would put a scare into the Russians.”

Coach Snyder’s words resonated soundly, as in the brief 3½ hours thereafter, his boys amassed an unprecedented tally of American and World bests. Some 8600 lucky attendees witnessed the breaking of 4 world marks and another tied, plus the setting of 2 American Records set and 2 more tied… all in rapid-fire succession in a meet that was all men’s events save for an exhibition women’s discus competition.

Set some 30 minutes south and east of Pasadena, Mt. SAC was known for its exceptional facility. Combined with ideal atmospheric conditions the stage was set for peak performances. The most noteworthy record to fall took place in the program’s second event of the evening, the broad jump, as the LJ was then called.

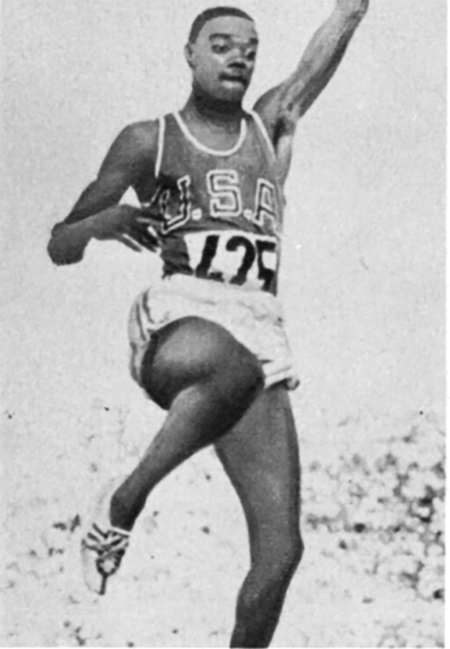

A 21-year-old junior from Nashville’s Tennessee Agricultural & Industrial State College (now Tennessee State University), Ralph Boston, eclipsed the oldest WR on the books, Owens’ 25-plus-years standard of 26-8¼. From his very first leap of the night, Boston was on fire. On his inaugural effort he stretched out well beyond 26-feet (7.92) but, as he sat back in the sand, was awarded just 23-10 (6.96) for his efforts.

Thereafter, the lanky leaper produced the best series that the event had ever seen, starting with consecutive marks of 26-¾, 26-6 and 26-1½ (7.94, 8.07, 7.96). For his fifth attempt, Boston extended his approach by an extra 6-feet (c2m), from where he sprinted for all he was worth before coming down to earth 26-11¼ (8.21) later, 3 entire inches further than any man had ever previously long jumped with legal wind. Observing, “This is the fastest runway I have ever competed on” Boston etched his name into the WR ledger.

The evening’s throwing events garnered 2 more WRs and another one tied. First, in the hammer competition, Hal Connolly broke his implement on his penultimate toss. Using a borrowed hammer, Connolly knew even before it landed that his final throw was in WR territory. At 230-9 (70.33), the American had become the first man to surpass 70m (229-8), while adding more than 5ft to his own WR.

In the shot, Bill Nieder exceeded 20m (65-7½) for the first time and improved upon his own pending world standard by 3 inches with a 65-10 (20.06) chuck. And finally, Rink Babka tied the discus WR when his platter landed at 196-6½ (59.91). Twice.

One more WR was set, in the last race of the day, the mile relay. The previous WR of 3:07.3 was set by Team USA in the final pre-Olympic meet prior to the ’56 Olympics. Four years later on this balmy summer’s eve, two teams of four men faced off.

Leading off for the A team, Eddie Southern (47.2) outsprinted Cliff Cushman (48.1). Southern handed off to Earl Young (46.4) while the B team’s Ted Woods closed slightly (46.2). The third legs were handled by Otis Davis (A team) and Jerry Siebert (B team) who both split 45.9. Jack Yerman had anchor duty and a 5y lead for the A squad and Glenn Davis carried the baton for the other guys. Davis quickly made up the deficit and a dogfight ensued. Yerman (46.1) refused to be passed and Davis (45.9) cracked just before the line. The two teams were timed at 3:05.6 and 3:06.1, surpassing the standing WR by 1.7 and 1.2 seconds respectively.

In the American Record category, Dyrol Burleson took to the metric mile like a Duck to water as he eclipsed fellow Oregon alum Bill Dellinger’s by 0.2 with a 3:41.3 win over Pete Close (4:42.7). Burly’s nifty AR was buoyed by a final go-around of 55.7 after having passed the 1320 in just 3:00.8… a nice display of pre-Olympic finishing speed.

An AR 6M occurred more by happenstance than design. Southern California Striders ace Bob Soth, had been recruited to pace Mal Robertson in an attempt for the latter to achieve the Olympic qualifying standard of 28:50. Soth had finished 3rd in the Olympic Trials 5000 and 5th at 10,000m.

At the conclusion of the Trials, Soth still lacked the Games standard of 13:45, but afterwards, managed a 13:38.8 at the Long Beach practice meet. On this night, Soth set off on a 24-plus-lap excursion, but pal Robertson was not up to the task, so instead, the Drake alum ground out a solo 28:56.0 to slice 5.8 seconds from the U.S. Record 29:01.8 that Buddy Edelen had set earlier in the year.

Determined not to be left out of the action, the sprint and hurdle events witnessed American bests, both in the form of tied marks. First, in the 100, following a terrible start Dave Sime caught the field at halfway and pulled away to tie the AR time of 10.1. And in the 110H, Lee Calhoun was given the nod over Willie May as both recorded brisk NR-equaling marks of 13.4.

According to the now-yellowing meet program the events began at 6:30 P.M. and concluded with the relay at 9:50. Power-packed into that tight timeframe was one of the greatest record-wrecking treasure chests ever witnessed in the Western Hemisphere.

When an AP reporter contacted Owens to let him know of the Boston long jump record and other results, the always humble legend went on record to say, “I’m happy to see the record broken, and I’m just thankful that it stood up this long.” The triple Olympic gold medalist continued, “This shows that progress is being made in track & field. It also shows that youngsters have come along today much better than they did 25 years ago.”

And the Russian comrades quivered.