AT THE NIGHT OF LEGENDS celebration staged as part of the national governing body’s Annual Meeting, the 4 members of the Class of 2019 were inducted into the USATF Hall Of Fame: Fred Thompson (Coach), Sandra Farmer-Patrick (Modern Athlete), Steve Lewis (Modern Athlete) & John Powell (Veteran Athlete). Said CEO Max Siegel, “These esteemed athletes and the late coach Fred Thompson have exemplified the best our sport has to offer. USA Track & Field is honored to recognize them for their achievements, dedication and service.”

USATF’s Hall Of Fame has 4 categories. Modern Athletes are eligible after they have been retired for 3 years. Veteran Athletes are eligible after being retired for 25 years. An athlete (or athletes) is inducted from each category every year. The Contributor and Coach categories alternate years. Meet this year’s 4 inductees:

Fred Thompson—Coach

Fred Thompson’s legacy goes far beyond New York City, and summing up his role as a “youth track coach and organizer” falls far short of what he accomplished. After his service in the army and law school, the former sprinter founded the Atoms TC in ’63. “He felt like if he could help people the same way he had been helped, it would make a difference in the lives of other youngsters,” says Cheryl Toussaint, the ’72 Olympic 4×4 silver medalist who came up through the Atoms and was Thompson’s assistant and successor as director of the Colgate Women’s Games.

Toussaint explained, “He saw blight in the community where he lived. There were no programs available to kids that would help them and get them to focus on something beyond just hanging out. He wanted to make sure they were directed in some positive way, and he felt track & field was a good place to begin. He felt it was one of the entry-level sports for most kids where it didn’t cost much more than a pair of sneakers.”

Thompson coached and organized despite working full-time as an attorney. His pupils made their mark on the sport. Some of his Olympic names included Grace Jackson, Diane Dixon, Joetta Clark, Michelle Finn, Meredith Rainey and Candy Young. “Track was secondary,” says Toussaint. “He espoused education, education, education. You couldn’t participate on his team if you weren’t up to par where you should be in school.” In ’73 he launched the Colgate Games, a series that provided competitive opportunities for women back when there were few. In the first year, more than 5000 competed. Thompson passed away in January 2019 at the age of 85.

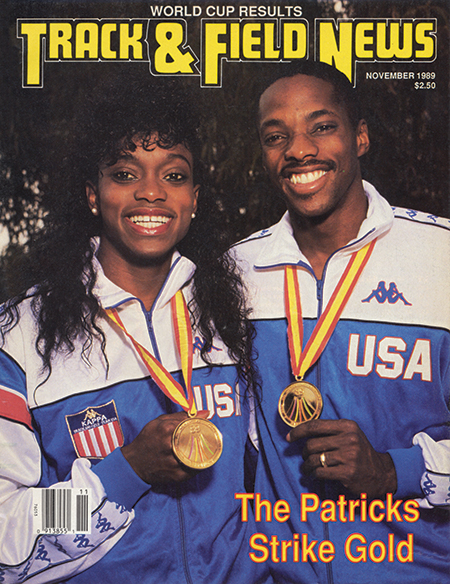

Sandra Farmer-Patrick—Modern Athlete

She ranked No. 1 in the World in the 400H three times, but before any of that happened, Sandra Farmer-Patrick had to get through the trauma of ’88. An ’84 Olympian for Jamaica, she opted to switch to the U.S.—where she had lived since she was 11—for the ’88 Games. “I ate, slept and thought American, so it was a natural thing to do to run for the country,” she says. Having made the big switch with no turning back, she was crushed to be disqualified for a lane violation in the Olympic Trials. “If I had stayed with Jamaica, I had a sure spot on their Olympic team. It was the biggest blow of my life because I felt like I was a woman without a country at that time.”

SFP roared back the next season with an undefeated campaign, a World Cup gold and U.S. Athlete Of The Year honors. “I made it my Olympic year,” she says. Though she had finished as high as 2nd in the NCAA while at Cal State LA, nothing in her collegiate career prepared the world for what Farmer-Patrick accomplished as a pro. She ranked No. 1 again in ’91 and matched that in ’92 after winning the Trials and getting silver in Barcelona.

Her fastest race came in ’93, when she clocked 52.79—a mark that still finds her =No 12 on the all-time list—for WC silver behind the WR of Briton Sally Gunnell. “To this day I say that it was the best race of my life,” she says, “because when I crossed the finish line, I couldn’t have given a tenth of a second more. It was all I had.”

Steve Lewis—Modern Athlete

There are frosh sensations and there is Steve Lewis. A 45.76 quartermiler as a prep, he exploded when he got to UCLA. At the Olympic Trials, he set World Junior Records of 44.61 and 44.11 and he placed 3rd in the final to make the U.S. team. In Seoul, few expected Lewis to challenge Butch Reynolds, who had recently lowered the WR. But Lewis went out hard and forced Reynolds to chase him. The veteran came close, but Lewis took the gold with his 43.87, a World Junior Record that stands to this day.

“I knew that I would have a good chance to medal,” says Lewis. “That was the goal really at the very least. Going to the final was just, well, let’s just see what happens. I didn’t even realize until looking at the jumbotron after the race that I actually won.” Three days later, he ran on the gold medal 4×4 that tied the WR of 2:56.16.

In ’90, two years after his Olympic win, he finally captured his first NCAA individual title. Then he was struck by a mysterious virus that sapped his strength: “I went to go see all these different specialists and no one could really figure out what was wrong with me. I was literally sick for about a year. I was still going to school at UCLA at the time. I really couldn’t train, and I didn’t think I would ever get back.”

The illness vanished in ’92 and Lewis again made it to the Olympics, winning silver. On the relay, he helped the team to another gold and a WR 2:55.74. However, a fall down stairs in a ’94 earthquake led to two back surgeries and a host of injuries, ending his career. “I was still young,” he says, “and I felt like I could have competed in at least two more Olympics.”

John Powell—Veteran Athlete

Rejection from the high school baseball team put John Powell on the path to being a legend in the discus. Leaving high school still a platter novice, Powell threw for American River JC and San José State, earning a 4th in the ’69 NCAA. The next year he placed 3rd at the AAU and in ’72 he made the first of three Olympic teams. For 7 years, Powell worked as a police officer and trained and competed in his off-hours.

One day in ’75 stands out. “Tom Jennings of the Pacific Coast Club said I had a meet in Long Beach. I didn’t want to go because I was tired… but I said I would go. I flew down in the morning and I was tired. I was leaning against a fence and got kicked in the foot by [former WR holder] Fortune Gordien. He said, ‘World Record today, Powell?’ I said, ‘I’ll tell you what, a nap is what I’m gonna do.’

“My first throw went out like a frozen rope to 205, a lot of power on it. I used my legs and timed it a little better on the fourth one and it went a World Record 226-8 [69.08] and hit an asphalt access road and the discus was damaged so bad it could never be thrown again.” He then flew back home to work his next shift. “When I got off at 2:00, the papers said, ‘Powell Sets World Record.’” He remembers his police days fondly: “You had hours of boredom and then moments of stark terror. It was a good job and I loved it.”

Powell, renowned for his technique, went on to earn bronzes in both the ’76 and ’84 Olympics and then captured silver at the ’87 Worlds. In a career notable for its longevity, he had 13 World Rankings over a 16-year period. He was ranked among the top U.S. throwers 19 times over two decades, with 5 No. 1s. ◻︎