The “Penetration” style of takeoff is explained by vault observer Bussabarger.

By David Bussabarger / Illustrations by David Bussabarger

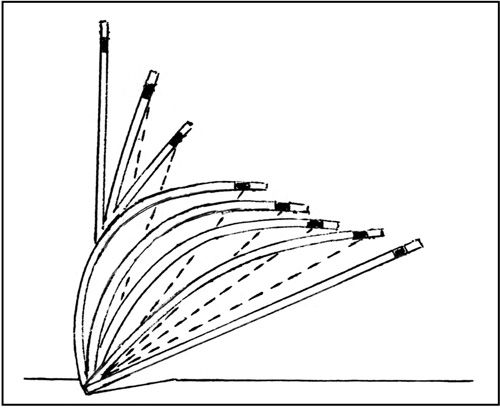

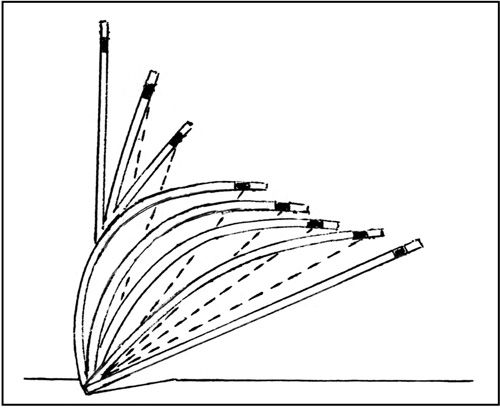

The fundamental principle underlying rigid pole vaulting was the double pendulum. Simply put its goal was to make the vaulter’s body into a pendulum rotating about the pole while the pole became a 2nd inverted pendulum rotating about the box.

Because the pole was rigid it could only move towards vertical in an underhanded rotational motion. As a result vaulters were forced to design their takeoff action around the limitations of the pole’s movement. Proficient rigid vaulters sprang directly upward as they left the ground in order to reduce takeoff shock and to generate overhand rotation in the pole. Immediately after leaving the ground the vaulter dropped his lead leg and pushed his chest forward and upwards towards the pole. At this point in the vault the vaulter literally became a pendulum rotating abut his closely spaced hands.

The first fiberglass poles that could bend reliably without breaking were introduced around 1960 (Herb Jenks’s Browning Sky Pole). Initially all the best fiberglass vaulters were accomplished rigid pole vaulters. As a result traditional rigid pole technique, including the double pendulum, was adapted to fiberglass vaulting with relatively few changes.

Common early technical adjustments included reducing the hand shift slightly during the plant so the hands remained farther apart during the vault and extending vertically before pulling and turning.

The concept of actively bending the pole was something new in vaulting so in the beginning vaulters typically only bent the pole 20 to 30 degrees.

The great exception to this trend was John Pennel (USA). Pennel became the 18th man over 15 feet with a metal pole at the young age of 20 in 1960. In 1963 he set his first WR with a fiberglass pole at 16-3/4.95m and went on to set six more WRs that year, culminating with a leap of 17¼/5.20m to become the first man over 17 feet.

Arguably more important were Pennel’s many technical innovations, particularly his very wide hand spread for the time (about 28”) and his total reinvention of the takeoff. Pennel realized that because of the pole’s flexibility, the vaulter could emphasize driving forward through the takeoff while springing off the ground in a forward-to-upward direction. This created much m

ore kinetic force of movement during the takeoff, which in combination with his wide hand spread and higher grip produced much greater pole bend (90 to 100 degrees). The writer calls this the “Penetration Style” takeoff. The great majority of elite vaulters adopted variations of this takeoff style from roughly the late 1960s onwards, a trend that continues to this day.

The salient point here is…

(1) Because of Pennel’s wide hand spread and penetrating takeoff action his body never became or acted like a pendulum during the vault.. Note that because of his takeoff and hand spread Pennel’s swing became focused on the sweeping action of his trail leg rotating about his hip. In other words he did not rotate about his top hand, a critical factor in establishing pendulum body movement.

(2) Because of Pennel’s penetrating takeoff and increased pole bend, the pole no longer rotated to vertical in an overhand fashion like a rigid pole. Note that many argue that because the theoretical axis of bending poles produces the appearance of rotational movement when charted, fiberglass poles rotate to vertical like rigid poles. It is the writer’s point of view that (A) This is in effect imaginary rotation. (B) The true movement of the pole in a proficient fiberglass vault should be plotted based on the movement of the top hand on the pole through the vault. This reveals that the pole has a rolling wave-like movement as it bends.

In conclusion, once the vaulter develops a proficient fiberglass takeoff with the hands on the pole more than roughly one foot apart and the pole is fully bent the double pendulum will be eliminated from the vault.

A related point here is Vitaly Petrov’s “free takeoff” concept. Petrov claims that fiberglass vaulters should retain the upward springing action seen in rigid vaulters (in coordination with extending both arms) as they leave the ground to improve pole rotation. Despite the fact that this concept has been widely accepted since the 1980’s, very few elite vaulters have used/use a free takeoff action (new 6m vaulter Timur Morgunov its currently its most prominent exponent). This is probably because it is more complicated and difficult to master compared to the penetration style takeoff. In addition, if, as the writer argues, fiberglass poles do not rotate to vertical, then there is no mechanical advantage for the free takeoff other than it slightly increases the angle of the pole as the vaulter takes off. It is certainly debatable whether or not this offers any significant advantage in itself.

It is the writer’s view that the primary reason for the increases in hand grip seen in elite vaulters over the years is the result of improvements in the execution of the penetration style takeoff. Petrov’s star pupil former WR holder Sergy Bubka (UKR) is reported to have had a hand grip of 17 feet. However it must be taken into consideration that Bubka was a massive one tenth of a second faster over the final 5m of the run than the next fastest 6m vaulter. Shawn Barber (Can) uses a variation of the penetration style takeoff, and has the highest hand grip for a 6m vaulter at 17-4½. WR holder Renaud Lavillenie (Fra) has the most pronounced penetration style takeoff the writer has ever seen and at 5-9 with only 11 second 100m speed his hand grip is about the same as Bubka’s.