By Jason R. Karp, PhD, MBA

Adapted from the book Running Periodization: Training Theories to Run Faster, by Dr. Karp.

“You can’t understand the value of a whole process by separating the parts from the process, or the process from the parts.”

The high school and college cross-country and track environment presents a unique training problem. Between the emphasis on racing and the desire for immediate results, runners’ aerobic development is often sacrificed for the sake of intensity. And that’s not ideal if the goal is to become a better distance runner. Runners and coaches need to adequately prepare for many races, sustain motivation and desire, and train with an optimal strategy.

Volume

Aerobic training volume is crucial for runners during their developmental high school and college years, if they desire to be good runners. While there is no magical number of miles to run per week to be successful, the best high school and college runners tend to be the ones who run the most, although it can take years to safely reach a higher level of mileage.

Many high school runners who run in college go from a low-mileage high school program to a high-mileage college program, which often leads to injuries. If a high school runner doesn’t run a lot in high school, he or she can’t just jump into running a lot in college. There must either be a bridge between high school and college training, or better volume preparation in high school to handle the college training. College coaches who train their athletes with high mileage also need to be careful recruiting high school runners who run low mileage in high school, lest they get injured in their freshman year of college from the much greater training load that awaits them. In this case, the runner should spend his or her freshman year of college adjusting to the higher volume, rather than follow the volume, intensity, and racing schedule of the rest of the team. Aerobic development takes a lot longer than anaerobic development. Although volume has a significant impact on every runner’s success, high school runners need to increase their mileage slowly and methodically, matching the training to what they can handle each year.

Injuries like shin splints (medial tibial stress syndrome) and stress fractures are common among high school runners, who are subjecting their bones to a new stress. From their current starting point, whether zero, 20, or 50 miles per week, slowly increase the mileage from the beginning of cross-country season until it’s time to back off to taper prior to the most important end-of-season races. Plan the cross-country season as one macrocycle, decreasing the volume during the final mesocycle. After the short transition phase following cross-country season, start increasing the volume again through the macrocycle of indoor track season, and finally again for outdoor track season. If there is no indoor track season, combine the winter and spring seasons into one macrocycle, and increase the volume after the transition phase following cross country until the final mesocycle of outdoor track season. All of this requires a methodical approach, focusing on aerobic training, and sprinkling in just enough speed work to improve speed and elicit performance peaks.

Perhaps the biggest training mistake that runners make is running too fast during their easy runs. High school (and, to a lesser extent, college) runners may be the epitome of this. Between the natural immaturity that accompanies young age and the competitiveness that accompanies the team environment, young runners often like to race each other, even when the run is supposed to be easy. If young runners always push the pace on easy days and do a lot of interval training and races, they can’t also do a lot of volume. To accommodate and progress with volume, intensity of easy runs must decrease, at least until the runner gets used to higher volume. College runners who are used to high volume can spend more time getting used to a higher intensity at their already high volume.

Not only are interval training (or race) days of low volume, the day before and the day after are also typically of low volume because those days often serve as easy, recovery days. Few runners are going to want to sacrifice a race by running a lot the day before. If a high school runner has a track meet on Tuesday and Saturday, that leaves Thursday as the only day of the week to focus on volume. If it’s possible to run longer the day after a cross country or track meet, that still leaves only Wednesday, Thursday, and Sunday to focus on low-intensity volume. This is the problem that high school runners (and their coaches) have, with many cross country and track meets scheduled throughout the school year. College runners also encounter this problem, albeit to a lesser degree because of races typically scheduled only on weekends. With all those races on the calendar, how do you train for them all?

The smart thing to do is to not train for them all. If high school and college runners race often, not all those races should be dealt with the same way. Not every race is so important that you must be tapered for it. Train through early-season races, even using those races as workouts to meet the purpose of the mesocycle or microcycle. For example, a cross country 5K race or a 3,000/3,200-meter track race can replace a VO2max interval workout; a college 8K/10K race can replace an acidosis (lactate) threshold workout; and an 800-meter/1,500-meter/mile race can replace an anaerobic capacity workout.

Intensity

In the developmental years, training intensity needs to be carefully controlled, with the major increase in training from year to year coming from volume, sprinkling in just enough intensity at the right times to get the job done and keep the athletes interested and motivated. The more aerobically fit runners are, the more they will ultimately get from their subsequent speed work. At a young age, training should focus on general skill acquisition and general conditioning, which can be used as a springboard to specific skill acquisition and specific conditioning as the athlete physically and psychologically matures. One of the confusing problems is that runners (and their coaches) get results when they run fast workouts. But hammering through more and more interval workouts is not how to keep getting faster. This is true for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is that anaerobic fitness is limited (you can only increase speed by so much). In contrast, aerobic fitness is virtually unlimited, at least up to the point that genetics will allow for further adaptation.

There are exceptions to the methodical, aerobic-volume approach. For example, if a high school student comes out for the cross-country and track teams because he or she wants to have fun, hang out with friends, or simply to get excused from physical education class, then, by all means, take the short-term approach and don’t worry about six months from now. Likewise, if the student-athlete is a senior, with no plans to run in college, then the training should also reflect that circumstance. If, however, a freshman comes out for the team and wants to find out how good he or she can become, then a long-term training approach that focuses on volume and carefully controls intensity is necessary. There are many reasons to run cross country and track; the student-athlete’s goals must always be of primary importance.

Training Program Design

The design of a high school or college runner’s training program is easier than that of other training programs because the structure is already provided as four distinct seasons (macrocycles): cross country, indoor track, outdoor track, and summer. (If there’s no indoor track season, then outdoor track becomes a larger macrocycle, with perhaps a slightly longer recovery/transition period following cross country season.)

All you have to do is divide those macrocycles into mesocycles, working backwards from the end of each season, and factor in recovery/transition phases following the final race of each season. Each macrocycle begins with a general preparation phase, followed by a specific preparation phase, competition phase, and recovery/transition phase. Repeat this pattern for each season, and you have an annual high school and college training plan. The duration of each phase (general prep, specific prep, competition, and recovery/transition) can be shortened or lengthened to accommodate the competition schedule of each season. Races during the general prep and specific prep phases should be trained through, using those races as workouts, so as not to sacrifice the aerobic training that needs to be done to be able to race fast during the competition phase.

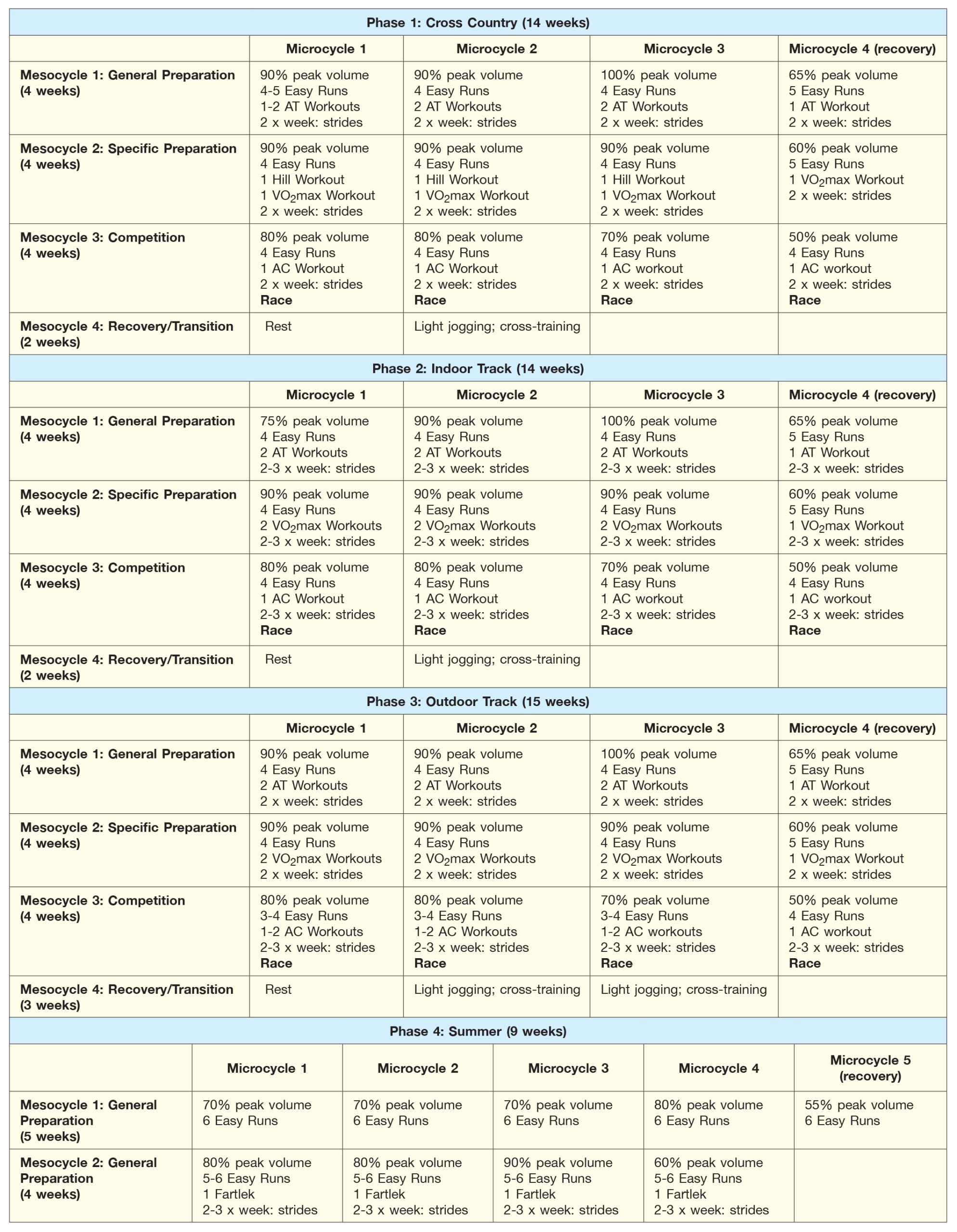

The following training program is for high school and college runners who compete in two or three seasons per year. The annual program is planned in four macrocycles: cross country (14 weeks), indoor track (14 weeks), outdoor track (15 weeks), and summer (9 weeks). The final two weeks of cross country, indoor track, and outdoor track are used to recover from the competition phase and transition into the next season. If your specific seasons are longer or shorter than 14 weeks, adjust the number of weeks in each macrocycle and corresponding mesocycles. For example, if the important races span three weeks instead of four, add a fifth week to the general preparation mesocycle. If you don’t have an indoor track season, bridge cross country to outdoor track with another macrocycle that focuses on general and specific preparation and eliminate the competition mesocycle.

The high school/college training program includes three four-week competition phases throughout the year, one at the end of each season. Other than the four-week competition mesocycle, during which you can focus on running fast races, all other races within each macrocycle should be trained through. Run early- and mid-season races as workouts that meet the specified target of that mesocycle. For example, a 5K cross country race in mesocycle 1 can be run as a threshold workout, with the amount of mileage on the day before and day after that you would normally plan if the race were a threshold workout. In other words, don’t back off before and after every race of the season, otherwise you’ll sacrifice the all-important aerobic development. Remember, you can’t expect your athletes to run very fast for every race all year or even all season. But when the training is planned well, they can run fast when it counts at the end of the season.

You can plan the training as concentrated blocks, using a linear periodization approach—general preparation of aerobic training followed in succession by acidosis threshold, VO2max, and anaerobic capacity. With a short time frame, you want to make sure you cover everything. It’s possible, however, especially with races throughout each season, to include a maintenance workout in each mesocycle to maintain the fitness factor you focused on in the previous mesocycle. For example, when you transition from acidosis threshold training in mesocycle 1 to VO2max training in mesocycle 2, feel free to take out one of the VO2max workouts and insert a maintenance acidosis threshold workout. Same in mesocycle 3—feel free to take out one of the anaerobic capacity workouts and insert a maintenance VO2max workout from mesocycle 2. Races themselves may also serve as maintenance workouts.

This program is best used as a template, adjusting the duration of cycles and emphases of mesocycles as needed based on the specific races you’re training for and your running strengths. For example, for runners training for 800 meters during indoor and outdoor track seasons, introduce anaerobic capacity (speed endurance) workouts during the specific preparation phase rather than wait until the competition phase. For college runners training for 5,000 or 10,000 meters, place greater emphasis on acidosis threshold and VO2max during the specific preparation phase. Emphasize the most important fitness factors during the specific preparation and competition phases for the runner and for the target race.

High school and college runners, who are young and can recover quickly from hard workouts, can also take a block periodization training approach by making slight adjustments to this template, doing three to four hard workouts (instead of two) in the first microcycle of each mesocycle (with a drop in volume to accommodate the higher intensity), followed by one hard workout in each of the next three microcycles (with higher volume). Races can substitute for workouts.

Dr. Jason Karp is a coach, exercise physiologist, best selling author of 13 books and more than 400 articles, and TED speaker. He is the 2011 IDEA Personal Trainer of the Year and two-time recipient of the President’s Council on Sports, Fitness & Nutrition Community Leadership award. His REVO₂LUTION RUNNING coaching certification, which has been obtained by coaches and fitness professionals in 26 countries, was acquired by International Sports Sciences Association in 2022. In 2021, he became the first American distance running coach to live and coach in Kenya. Running

Periodization and his other books are available on Amazon.