A Practical Guide To Speed & Speed Development

Mike Thorson, Former Director of Track & Field/Cross Country

at the University of Mary, Bismarck, N.D.

Speed—Stride length multiplied by stride frequency. It is defined as the ability to perform specific movement in the shortest possible time.

Velocity—the rate of speed in a given direction.

GOAL (Mission Statement) The goal of any speed development program: .01/stride Improvement. Example: time improvement in a 100m dash would be .5. 40m—.2. (Seagrave, Speed Dynamics)

SPEED CAN BE SIGNIFICANTLY IMPROVED THROUGH A SYSTEMATIC TRAINING PROGRAM

Speed is both a biomotor quality and a motor skill. Sprinting can be learned through educating the neuromuscular systems in the body and enhanced through basic learning skills. Speed = A neuromuscular skill. It is in the motor unit where speed begins and must be perfected! The techniques involved in sprinting must be rehearsed at slow speeds and then transferred to runs of maximum speeds.

Remember, sprinting involves moving the body’s limbs at the highest possible velocity. The stimulation, excitation and correct firing of the motor units make this possible for high frequency movements to occur. This complex coordination and timing of the motor units and muscles must be rehearsed at high speeds in order to establish the correct motor patterns.

When we talk about speed, it is normally in terms of runs of 95-100% intensity over 30-60 meters, or up to six seconds of running at maximum effort.

Speed is the product of two very basic parameters: stride length (SL) and stride frequency (SF). Of the two, SF, which is measured in single strides per second, is the most important.

The Speed Equation: Stride Frequency X Stride Length = SPEED. That equation, however, means very little to your typical sprinter. In layman’s terms: The goal of the sprinter is to put big forces into the ground in a short time. The longer an athlete is on the ground the greater the loss of stride frequency.

THE MARAUDER SPEED PROGRAM IS BASED ON FOUR KEY CONCEPTS

1. Speed improvement results from training at continuous high, varying intensities! Speed training must be done at maximum speeds with many repetitions to train the correct motor patterns.

2. Skill development (sprint mechanics) must be learned, rehearsed and perfected before it can be done at high speeds.

3. Flexibility must be developed and maintained on a daily basis.

4. An athlete’s strength development must be parallel with developments and increases in speed. (Functional Strength=SPEED)

THE BASIC COMPONENTS OF MARAUDER SPEED

1. SPRINT MECHANICS An athlete may run only as fast as his/her technique allows. Only through good sprint mechanics will an athlete function at the ultimate/optimal stride length/stride frequency.

2. FLEXIBILITY Only through gaining flexibility through a series of stretching exercises and dynamic warmup drilling can athletes gain the range of motion required for top-level sprinting.

3. NEUROMUSCULAR (CNS) FIRING STIMULUS The brain begins all movement patterns by sending impulses to the nerves, causing muscles to contract. Speed gains result from a perfected activation of motor units implemented through correct training.

4. MAXIMUM VELOCITY TRAINING Only through brief intervals of maximum velocity will the athlete develop and “educate” the proper motor patterns. “Very fast training” at near 100% intensity is needed if the athlete is to be “fast” on meet day! An athlete cannot ask the body to do something in competition that it hasn’t been trained to do. Maximum velocity training needs to occur on a very continuous year-around basis. Remember, “If you don’t use it, you lose it.”

5. STRENGTH can be gained through a number of different means, including regular weight training, body weight exercises, hill running, bounding, multi-jump training, multi-throw training, therabands and plyometrics. Your strength and conditioning program should be based on exercises and drills involving multiple joint actions and movements. Sport skills require multiple joint actions timed or fired in the proper neuromuscular recruitment patterns.

6. SPEED ENDURANCE Anaerobic endurance is a key ingredient needed in order for a sprinter to stay at maximum speeds longer and cover longer distances (7-20 seconds, 60-150m). This can be accomplished through interval/repetition training. Example: 2 X 3 X 5 reps with 2-5 minutes recovery/rep/8-10 minutes recovery/set

7. ACCELERATION Developing proper leg angles and training an acceleration pattern are essential to speed development. Acceleration mechanics in their purest form involve falling and recovery action with every movement affected by the previous one. The goal is to reach maximum stride with an efficient trained pattern in a minimum amount of time.

8. BREATHING PATTERNS Specific, rehearsed breathing patterns have a significant impact on sprint performance. It has been proven that acceleration and explosion improve when an athlete uses a pattern of inhaling/exhaling. Soviet research has long shown that more force can be produced when the athlete holds his breath. (Valsalva Maneuver)

9. RECOVERY/REGENERATION Athletes who are involved in regular regeneration/recovery treatments are able to increase the volume of high intensity work by as much as 40%. Many coaches/athletes do not understand that it can take up to 48 hours to recover from a high intensity CNS/power workout. Sauna, pool, massage, ice bath, massage sticks and form rollers are all useful recovery means. Athletes and coaches should understand too that nutrition, hydration and sleep can play a large role in recovery.

1. Sprinting is the result of neuromuscular coordination; a motor learning process.

a. Force production and movement and velocity have to be optimal rather than maximal.

b. With higher speeds, the time frame becomes smaller for muscle contraction and relaxation. Thus, it is more difficult for the CNS to distinguish and coordinate the driving forces of extension with antagonistic actions of flexion in leg recovery. It is very important that the agonistic and the antagonistic muscle activities not hinder one another.

c. Repetition of this neuromuscular facilitation in the correct firing sequences seems to establish an automatic response in performance. Only through repetition at high speeds can an athlete educate the proper muscles to be used and the order to be fired.

d. The neuromuscular recruitment and activation of motor units (skill) is most effectively developed only during fatigue-free seconds of anaerobic alactic work. A sprinter does not only improve performance by activating bigger motor units in greater quantities but by synchronizing their activation to produce a greater rate of force development.

2. The base training for speed is SPEED. Thus, it should be trained year-around. Intensity is increased as competitive performances are required, but to neglect speed and technique for several months of the year is a serious mistake. This was often done in the past to obtain so-called “base work” prior to training speed. “If you train slow, you will be slow.” If you want to be fast, train FAST!

3. No fatigue can be present when speed training is being implemented. Athletes must have complete or near recovery if the athlete is to receive the maximum training effect. An elite level athlete needs 24-36 hours of rest or very low intensity work prior to a maximum speed training session.

4. Develop speed before speed endurance in any session or cycle.

5. Increase and decrease intensity to continually stimulate the CNS and avoid the movement stereotype. In other words, vary speeds and train at different intensities. Remember that practice does not make perfect, it makes permanent.

6. Emphasize neuromuscular coordination over strength and conditioning.

7. Speed should always be trained before strength in any session.

8. Acceleration and stride frequency do not develop without strengthening associating muscles to be fast and powerful.

9. Always choose exercises that are specific to sprinting and train for performance and not work capacity.

10. It is important to stimulate the CNS on a daily basis.

11. Medium loads with a fast series of repetitions are typically what are needed for the sprinter. Heavy loads, however, will be needed to aid in the improvement of the acceleration phase where power is needed. Remember, however, that too much work with maximum loads and slow speeds will develop muscle memory that is non-productive for the sprinter.

12. Choose multi-joint exercises over part movement exercises and optimally in the same firing sequence that a sprinter would employ.

13. Train for muscle balance and amplitude of movement. Programs must address all muscle groups and balance in strength development. Many injuries are the result of an imbalance in the antagonist muscles.

14. Address postural needs first and foremost. The CORE of the body is critical to performance.

15. Employ the same group of exercises long enough for a positive training effect (4 weeks). But not too long to cause a dynamic stereotype or staleness. Athletes and muscles need variety and varied stimulus.

16. Don’t think that strength work has to be done in the weight room. Sled pulls, tire pulls, hill running, hurdle hops, multi-throw/jumps and circuits can produce some significant functional strength gains.

17. Training can have a huge effect on fast/slow-twitch muscle fibers. Although to a degree this is genetic, training can have a huge effect on the recruitment and utilization of the correct fibers. Too much slow endurance work will recruit the intermediate fibers to assume properties of slow muscle fibers. On the other hand, more high intensity training can train the intermediate fibers to take on the properties of fast-twitch muscle fibers.

ACCELERATION

Acceleration (defined) the rate of change in velocity. It allows the sprinter to reach maximum speed in an efficient, minimum amount of time. Most sprinters reach maximum speed between 30-60 meters. Very seldom in team sports do athletes go beyond the acceleration phase. They are constantly stopping, starting and changing directions.

Acceleration may be the most trainable of the speed components.

Mechanics of Acceleration

Posture The alignment of the body is critical, with posture being dynamic—constantly changing with every step. Remember the so-called lean comes from the ankle and not the waist.

Arm Action The arms assist to produce force and aid in balance so that forces can be applied toward the ground.

Arms/Charlie Francis All sprinting is controlled by the arms according to the late Canadian sprint coach, Charlie Francis. When neurological pattern was researched it revealed that the arms do precede the legs and the faster the arms move, the faster the legs will in return.

Leg Action The emphasis is on the backside mechanics—the legs are pushing back behind the body during the first steps/strides. The pushing action begins in the first 4-6 steps, after which a sprinter is attempting to get into the “hips tall” sprint position.

Acceleration Pattern It is necessary in order to obtain the correct force application and proper transition to top speed to have the proper acceleration pattern. The pattern typically sees each step increasing until full speed is achieved. Many athletes take steps that are too long, hoping to achieve top speed quicker. Typically this causes just the opposite effect.

Force Application The goal in applying force is to create a positive shin angle so that the foot initially contacts the ground behind the center of gravity. Quite often the opposite occurs, thus a braking action when the foot gets out ahead of the center of gravity and causes a braking action. A coaching cue is to have the sprinter get the foot down as quickly as possible—you can only apply force if the foot is on the ground.

Acceleration Training Improvement in acceleration is closely linked to gains in power. Gains in power will result in the ability to produce higher amounts of force more quickly, thus decreasing ground contact time. Power (defined) is the rate at which work is done. Work divided by time = Power.

Acceleration Breathing Pattern The athlete will typically hold his breath (the in if you are working in and out breathing) during the acceleration phase before breathing out during the transition to the maximum velocity phase.

Acceleration Drills There is no substitute for the real thing. Therefore, the best way to train acceleration is to do just that and do not deviate very much from true acceleration work (drills). An example of acceleration work just using the body would be simple Falling Starts.

DRILLS:

1. Stick drills (experiment with spacing)

2. Harness Sprints (moderate resistance))

3. Sled Pulls (Always use the 10% rule—the resistance of the sled should not slow the runner down more than 10%)

a. React and Go drills

b. From a 180-degree turn

c. From back lying prone

d. On stomach

e. Drop and go

BALANCE

Balance may be the most neglected component in training. Yet, it is the most important component in athletic training because it underlies all movement. It is a very simple task, but is highly complex when it comes to sprinting.

Balance does not work in isolation when it comes to athletics. Things such as coordination and agility depend on a well-developed sense of balance. The ability for the sprinter to produce force at the right time, in the right plane, and in the right direction, is highly dependent on balance.

Balance and actually sprinting and running involve the body repeatedly losing and regaining control of its center of gravity because a runner (sprinter) is always moving. Balance can be improved through a variety of different sensory exercises.

A mini tramp, K-board, foam blocks or other means of equipment can certainly be used to train balance. But always remember the best equipment is the body itself.

Examples of balance training activities:

1. Hurdle Walk/Hurdle Walkovers (Regular and with eyes closed)

2. 180 and 360-degree turns/jumps (regular and eyes closed) Also called Half Turns/Full Turns. Respond to caller’s signal

3. Green Light/Red Light—Stop on one leg each time and hold in a balance position in response to a caller’s signal

Nearly any type of dynamic warmup drill can be used as balance training by merely having the athlete close eyes. Athletes will discover an entirely new sensory experience when drilling with eyes closed.

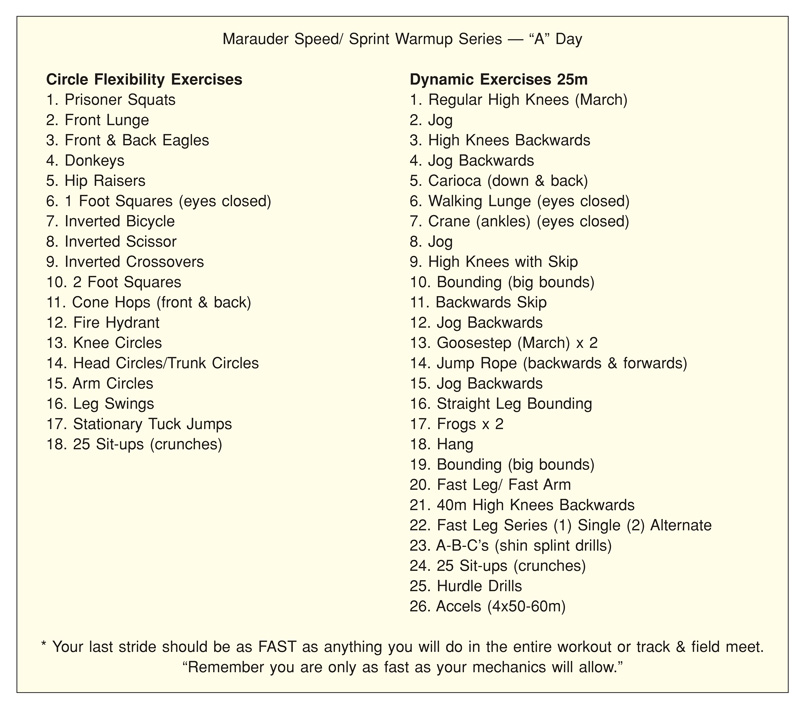

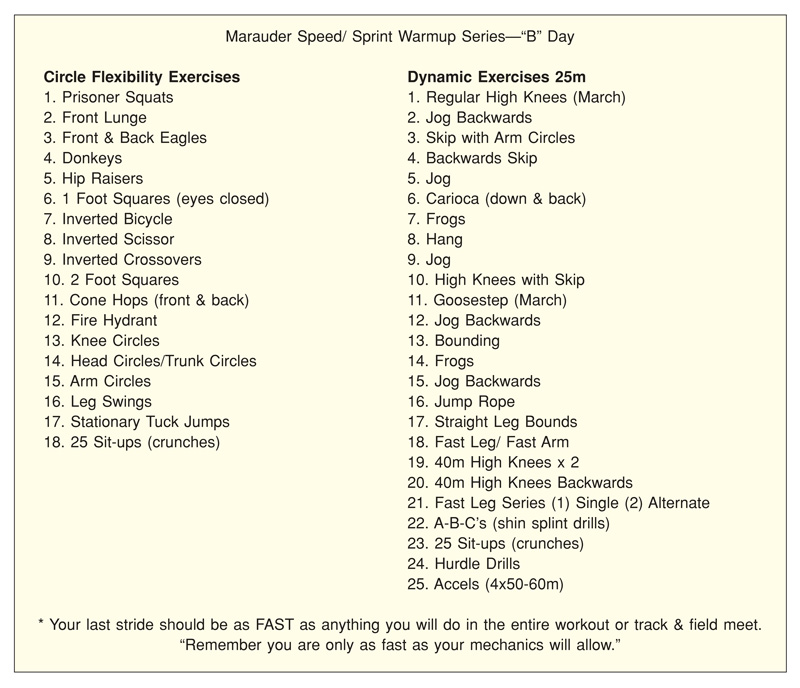

WARMUP

The warmup prepares the body for the training session, both from a physical and mental standout. It basically reduces the number of muscles that can be strained or hurt along with preparing the body to perform. It can be highly important in rehearsing the specifics of the event if structured and done properly. Skill development can and should take place in the warmup. Proper warmup not only prevents injuries and prepares the body, but improves sprint mechanics, flexibility, power, balance and strength. Thus, the warmup is a speed development improvement tool in itself.

Different types of Warmup:

1. Dynamic Continuous Movement

2. Static Flexibility (Research has shown that static stretching should be for the most part done at the completion of the workout)

3. PNF

4. Medicine Ball

5. Skipping Rope

6. Games (Tag, Relays)

SPRINT MECHANICS

A sprinter is only as fast as his mechanics will allow!

The principal mechanics keys/points:

1. The head is held high and level with the eyes looking straight ahead. No rotation of the head with a loose jaw and chin down (head steady).

2. The torso is erect and in a position of “good” posture. Instruct athletes to run tall with chest up. The body will be nearly vertical at high speeds (slight forward lean in some cases).

3. The hand of the driving arm comes up shoulder level (front-side mechanics). Arms should be bent at 90-100 degrees. Hands should drive back 6-8” behind the hips on the backside. Remember that all sprinting is controlled by the arms and that the arms precede the legs. Arms drive the legs!

4. The shoulders are relaxed, with the thumbs up and the elbows turned in toward the body.The arms should not cross the mid-section. The shoulders are down—not hunched causing tightness in the upper body.

5. The hips are high enough above the ground to allow the driving leg to extend fully to the ground.

6. The ankle fully extends at the end of the leg drive. Good knee lift is essential—thigh should be parallel or horizontal with the ground.

7. Concentrate on running smooth—no bouncing.

8. Ground contact should be with the ball of the foot, behind or slightly underneath the body’s center of gravity with an active foot strike. The goal of the athlete should be to impact the ground with a foot that is moving backward—think of a child riding a scooter or skateboard. The foot should be pushing backward before it impacts the surface. Sprinting is a pushing action and not a pulling action. Ground contact for 100-200m athlete should be ball of the foot, 400-800m runner the arch. By contrast, the 1500 meter runner will have ground contact with the entire foot.

9. Feet should be straight ahead during foot contact and in the dorsi-flexion position (toes as close to shin as possible—cocked)

10. Avoid excessive rear-side mechanics (actions). Stress high hips. Problems associated with excessive backside actions:

a. Increased recovery time which results in slower step-rate (stride frequency)

b. Increased load on the hamstrings which have to assist in the recovery process. Greatly increases the risk of injury!

c. Decreased knee lift (front-side mechanics) because knee lift is inhibited when the hips are low and there isn’t enough time for them to be lifted higher with the late recovery. This results in less powerful foot contractions.

11. Relaxation: All athletes should be striving for relaxation. Focus on using muscles that are required for running and stabilization. Even the face should be relaxed. More importantly, learn to switch off all muscles that are not required as much as possible.

SPRINT MECHANICS TEACHING CUES

1. Cocked foot (dorsiflexion) no dangle

2. No butt kick

3. Tight back, stomach and butt

4. Run tall, Chest up (aids in keeping hips tall)

5. Knee up, Toe up, Heel up

6. Speed up the arms (Arm Speed)

7. Close the angle on the arms (short levers are fast levers)

8. Thumbs up and turn elbows in with arms

SPEED DEVELOPMENT EXERCISES/WORKOUTS/SAMPLES

1. Maximum Velocity Training

a. 3 x 30 m with blocks/spikes (4 min recovery)

b. 2 x 3 x 50m with blocks/spikes (4 min recovery/8 min/Set)

c. 2 x 20m, 30m, 40m from 3 point/spikes ( 4 min recovery/(8 min/ Set)

2. Speed Endurance

a. 4 x 150m @ 98% w/spikes (5 min recovery)

b. 2 x 2 x 150m @98% w/spikes (5 min recovery/10 minutes/Set)

3. Acceleration Training

a. 4 x 40m with standing start (3 min recovery)

b. 4 x 50m Hill Sprints (3 min recovery)

4. Ins and Outs (Breathing pattern work over different distances)

a. Block Starts

b. Flying 30’s

4. Resistance Training

a. Weight vest sprints

b. Uphill Sprints

c. Sled/Tire Pulls

d. Stairs

e. Parachute

5. Assisted Training

a. Downhill Sprints

b. Towing (Tube/Cord)

**The 10 % rule should be in effect for both assisted and resistance training. No more than 10% of the athlete’s body weight should be used when providing overload for resistance. And the time should not be slowed by more than 10%. The same is true of assisted training: the athlete should not increase speed by more than 10%.

CONTRAST TRAINING

This is one of the best ways to develop pure acceleration and maximum speed. It involves combining resistance training and assisted running followed by the actual race model run (“the real thing” over acceleration or velocity distances).

POOL TRAINING

Pool workouts and hydrotherapy have long been used for rehabilitation. They also can be used for recovery and become a part of regular training programs. The pool can be used for strength gain improvement, skill development, and flexibility employing deep water intervals and regular swimming.

MENTAL/PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS

One of the trademarks of successful coaches is their relationships with their athletes. Successful coaches understand that coaching at the end of the day involves people, that it involves relationships.

1. The goal is to have athletes feel fast and successful

2. Create training that has positive outcomes

3. Have a passion for athletes and training (Display that)

4. Care!! Show athletes you care about them—on the track and off!

5. Develop trust and respect with athletes

6. You need to develop the ability to work with athletes that “operate outside of the box.” Understand that not all athletes will march to “your drum.”

7. Create a positive atmosphere with positive energy

8. Make athletes believe that anything is possible and that the key to obtaining goals is proper preparation (PP).

9. You as a coach should have goals and they should closely correlate with the athlete’s goals. Understand and communicate with each other!!!

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this speed presentation is to provide a practical and simple guide to speed and speed development. It is our goal that we can provide both coaches and athletes alike a basic, yet somewhat technical understanding of speed and what is required to develop and enhance it.

For more information and questions: Mike Thorson—mthorson@bis.midco.net (701.426.3080)

REFERENCES

1. Francis, Charlie, The Charlie Francis Training System E-book

2. Gambetta, Vern , Gambetta Method, 2nd Edition, 2002

3. McFarlane, Brent , The Science of Hurdling and Speed, 4th Edition, Canadian Track and Field association, 2000

4. Pfaff, Dan, Conversations, Handouts, Clinic

5. Seagrave, Loren, Speed Dynamics, Conversations, Handouts, Clinics

6. Winckler, Gary, University of Illinois, Handouts, Clinics, Conversations