A collection of statistical comparisons showing how much U.S. male javelin throwers need to improve before challenging for medals on the world stage, with suggestions as to how this may be accomplished.

By Don Babbitt, University of Georgia

Introduction

The United States has had a moderate level of success in the men’s javelin throw at major championships such as the Olympic Games and World Championships over the past 35 years, dating back to the first IAAF Championships back in 1983. However, in more recent times, this success has dropped off and it is now a rare occasion that a U.S. men’s javelin thrower will even qualify for the final in a major championship (see Table 1). For a country of 326 million inhabitants with a strong sporting culture, especially with regard to throwing things, it is quite an underwhelming performance. It is obvious there must be some issues within the developmental system that are not allowing the U.S. to keep up with the other javelin throwing powers in producing world class javelin throwers. The purpose of this article will be to examine and discuss four critical elements that are thought to be part of this current state of affairs:

1. Characterize the development structure and recent trends within the U.S. men’s javelin system.

2. Identify what levels of performance are needed to be competitive at the international level and the major championships.

3. Identify factors within the U.S. men’s javelin development system that could be holding back greater development.

4. Offer potential solutions to meet these performance targets.

To begin, let’s look at how javelin throwers are developed in the U.S.. The primary means of development for javelin throwing within the United States is through the school systems. High schools, rather than clubs, are much more likely to be the athlete’s first exposure to the event. Within the United States there are only 18 states which contest the javelin in high school, with the population of these states making up only 28.3% of the total U.S. population. Although, the population of the states that do get exposed to the javelin in high school is roughly 92 million people, large warm weather states that produce many high level baseball and football players, such as California, Texas, and Florida are not in this group.

Characterization of U.S. Men’s Javelin Development

Over the past 15 years the average level of the top javelin throwers coming out of high school has remained fairly steady, and has not shown signs of an obvious decline. Performance averages for the top 10 throwers in high school each year have fluctuated between 76-83% (~64-68 meters) of the international “A” standard for a given year as indicated in Figure 1. It is important to compare the performance of the athletes relative to that of the “A” standard (the performance needed to automatically qualify for the major championship that year), rather than just use the actual distance thrown, since the “A” standard will often change from year to year. In addition, the “A” standard is normally adjusted based on the performances of the collective group of international throwers so it acts as a good barometer to measure the increase in international performance as a group. This is what is most important to assess when trying to measure one’s performance advancement.

Upon completion of high school, which can be equated with the end of the Youth or U-18 stage of competition, the next step is to transition to college or university competition. It is in this stage, when the developing javelin thrower is between the ages of 18 and 23, that he is part of a well-funded NCAA system that includes comprehensive coaching, medical and psychological support, along with world class facilities and competition schedules. As indicated in Figure 1, the average of the top 10 best performers at the NCAA level has hovered between 87-93% (~71-76 meters) of the international “A” standard for that year. This age group, which encompasses both the Junior (U-20) and U-23 categories of competition, is on par with the other top javelin throwing countries in terms of depth of performance.

The post-collegiate stage of development for men’s U.S. javelin throwers sees the group having to deal with a more challenging situation with regard to coaching, medical, and other support services. It is this transition, from having almost every need being taken care to sometimes taking care of everything yourself, that provides the biggest test. Despite these challenges the average of the 10 best performers of the post-collegiate group has been consistently higher than what has been seen for the top 10 NCAA throwers each year at 91-95% (~75-79 meters) of the international “A” standard each year. However, this increase is minimal.

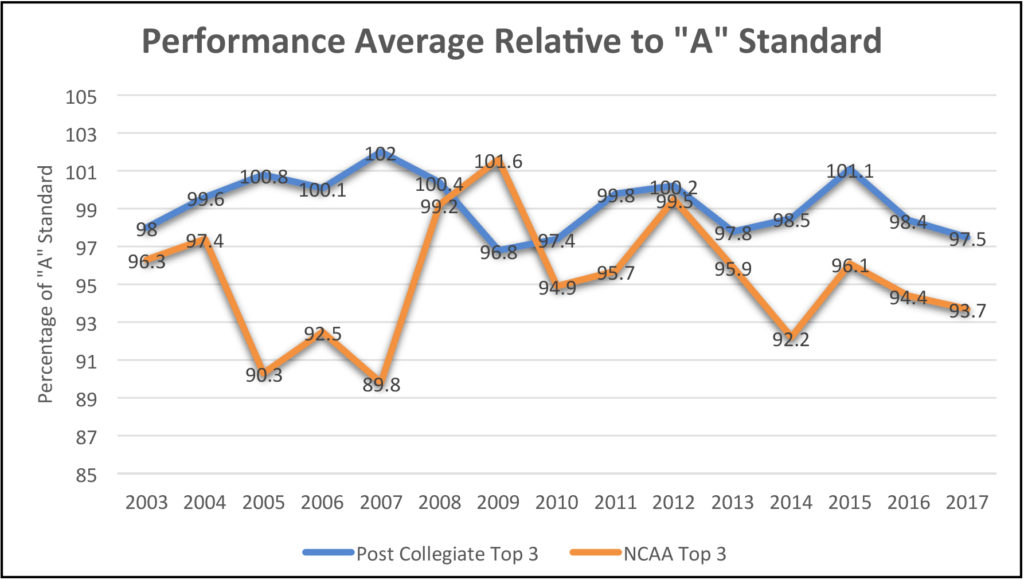

Now that the measures of performance for each of the developmental levels have been quantified, the next step is to focus more closely on the top three competitors in both the NCAA and post-collegiate group since each country is only allowed to send a maximum of three competitors per major championship. By focusing on the top three throwers from each group, it will allow one to see what level of performance the best throwers, who have a real chance to make the major championships, are actually achieving. When these calculations are tabulated, one can see in Figure 2 that the average of the top three performers from the NCAA group registered between 90-101.6% of the international “A” standard for the years 2003-2017. In this same time span the post-collegiate group registers between 97-102% of the international “A” standard. What appears to stand out is that the average performances for the NCAA group and the post-collegiate group are very similar and overlap in some cases. This seems to indicate that there is not much more development going on with the top throwers in their post-collegiate years.

The fact that the performance level of the top throwers in both groups is right near the “A” standard suggests that they are able to produce results that do meet the “A” standard, but that these throwers rarely throw past this more than once in a given season. The progress seems to end once the “A” standard, which is currently 83 meters, is reached. This notion is supported by the fact that the U.S. has had 13 male throwers in history who have eclipsed the 83-meter barrier, while only a mere 3 have gone on to throw more than 85 meters (see Figure 3).

Javelin Performance at the International Level

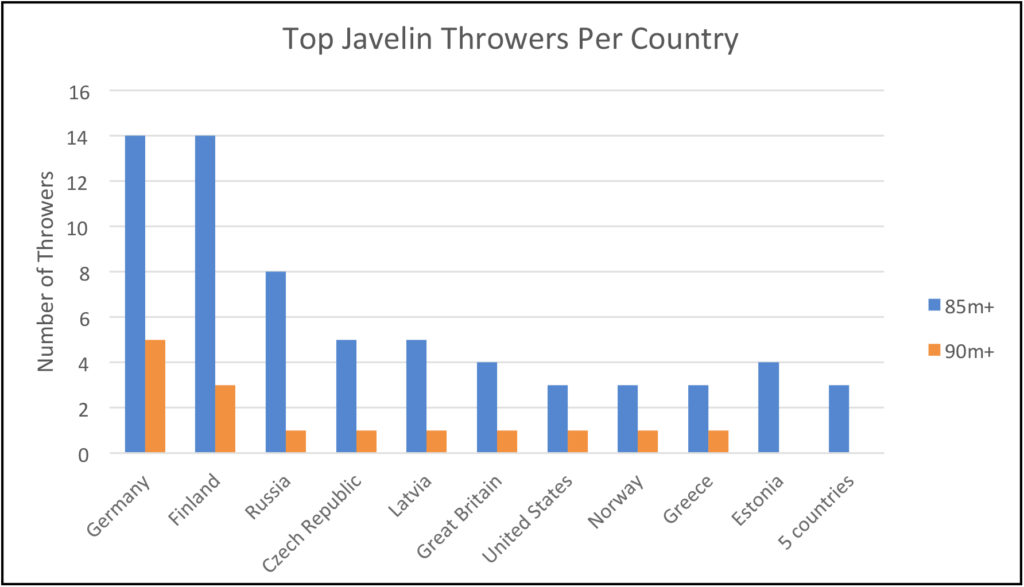

With today’s current javelin performances at the international level, it is almost always necessary to throw at least 85 meters to have a chance at a medal at a major championship. This type of high-end distance has only been achieved by three U.S. athletes with the new rules javelin (Tom Petranoff, Tom Pukstys, and Breaux Greer). Petranoff earned a silver in the 1983 World Championships, and Greer a bronze in the 2007 World Championships. It should be noted that all three of these athletes have now been retired for at least 10 years at the time of this writing.

Examination of Figure 3 shows clearly that the U.S. who tied for the same amount of high caliber throwers as much smaller countries like Norway and Greece, and well behind the javelin throwing powerhouses of Germany, Finland, and Russia, has a high performance javelin tradition equaled or surpassed by many countries with a much smaller in population than the U.S.

After spelling out the current levels of U.S. men’s javelin throwing, let us now examine actual performances achieved at the major championships by U.S. throwers and how they compare with that of the medalists. To begin, let’s look at the actual performance that were achieved at the major championships and report them as a proportion of the A standard for that given year. These results are summarized in Figure 4. As expected, the top American performance at the major championships was generally 6-7% below what was needed to be in contention for a medal.

In only two cases during the 2003-2017 time frame did an American javelin thrower achieve a medal-producing level of performance. The first was Tom Petranoff who earned a silver medal at the 1983 World Championships. In 2004, at the Athens Olympic Games, Breaux Greer was able to produce the farthest throw in the javelin competition at 87.25 meters. However, this was done in qualifying and did not carry over to the final in which this result could have won a gold medal. Greer was able to come back to earn a bronze medal at the 2007 World Championships in Osaka, Japan, producing a result that was 106.1% over the A standard for javelin that year. In the past 15 years, however, American javelin throwers have not been able to come close to producing a performance that can get them in contention for winning a medal at this level of competition.

The next question that must be asked is what is the cause for this lack of results in major international competition? Is it that the performance levels are too low for the American throwers going into the meet, or is it a lack of execution at the big meets? The answers seem to indicate that it a combination of both. In order to complete in a major championship you must hit a qualifying standard within a given qualifying period to show you are worthy of participating in such as meet. However, hitting one long throw, and maintaining a high standard of throwing are two different things. The average of the top three marks for the three medalists and the top performing American javelin thrower going into major championships are presented in Figure 5. This charting format gives a much clearer picture of the level of throwing fitness going into a meet, for it shows the eventual medalists almost always had a three-meet average of better than 100% of the A standard going into the meet, while American javelin throwers, with the exception of Breaux Greer in 2004 and 2007, had an average below 100% of the A standard. It was on only three occasions (~8% of the major championships during this time frame) that a men’s javelin medalist had a three-meet best average below that of the A standard (Kovals 2008, Murakami 2009, & Walcott 2012) leading into the major competition. All were first-time medalists.

Now, turning to execution in competition, the specific question that needs to be answered is how well does the thrower perform relative to the fitness level that he is taking into the meet. An attempt to quantify this result was done by taking the performance result from the competition and divide it by the average of the top three meets of a given athlete going into the competition. The result of this calculation was termed the championship execution quotient. Examination of Figure 6 shows that it was rare to see American javelin throwers produce a championship execution quotient higher than that of the medalists. Some of the notable instances when this did happen was with Greer (2004), Furey (2009), Dolezal (2013), and Hostetler (2017).

It should be noted that one potential explanation for these mediocre execution quotients is that the American performances at the major championship were done in qualifying, where there are only three throws, so it is hard to directly compare this result directly to meets where they had a full complement of six throws, as they did in their other competitions. On the other hand, the reason that (in all but Greer’s case) the throwers were unable to advance to the final, despite a good performance quotient, was their performance average going in to the meet was too low (see Figure 5).

Figure 6: this chart shows the major championship execution quotient, which is a measure of how well a performer throws relative to the average of their three best meets going into a major championship. It is calculated by dividing the thrower’s performance at the major championship by the average of his three best competition results leading into the major championship. The result comes out as a percentage and is listed on the y-axis of this chart.

To highlight these data further, Figure 7 provides trend lines for performance data for each of the four groups. This makes it easier to see what the trends are in performance over the past 15 years. One can see that from Figure 7 that the execution quotient for the American javelin throwers has tended to rise over the years, yet it is still far behind that of the medalists. This implies that there is much work to be done in order for U.S. male javelin throwers to be contesting for medals at major championships. They must both increase their average meet performance, and not settle for just getting the A standard, and they must increase their execution quotient and do a better job of maximizing their potential at these meets.

Pan American Games

Interestingly enough, the U.S. men’s javelin throwers have been quite successful at the Pan American Games in both winning medals and producing high execution quotients. In the four Pan American Games that have been contested in the 2003-2017 time period, the U.S. male javelin throwers have produced a medal at each championship with an execution quotient over 100%. However, if one looks at the performance quotient for these four throwers after the preliminary rounds one will see results that are very similar to what is seen at the major championships. These results are listed in Table 2.

This could be explained by a couple of possibilities. First off, these throwers all threw their best throws (all of which were seasonal bests, except for Greer, who was very close) in the final. By having the extra three throws in the final, they had more chances to get better than they had in major championships. Secondly, being in a competition in which one knows he can be competitive, even if one starts off slow, gives one the confidence to get it together over six competition throws instead of packaging the pressure into three throws with an uncertain advancement standard. Going forward, these are two critical perspectives that need to be considered and addressed if progress is to be made in improving performance at the major championship stage.

Factors Holding the U.S. Back

In determining what has hindering the U.S. from being more successful at the international level, it appears that the post-collegiate portion of development must be enhanced. For the past 15 years the U.S. has been very good at developing a large pool of javelin throwers each year who can throw 73-76 meters while in their early twenties. The athlete pool at this level has been deeper than any other country, including powerhouses like Germany, Russia, and Finland. Figure 8 shows the breakdown of the javelin performance pools by country for last season (2017). One can see that the U.S. also has a considerable number of active throwers with personal bests in the 78-80-meter range as well, but there seems to be a sharp cutoff in performance once throwers get to the 82-83 meter range. This distance also happens to be where the international A standard is, which is also in line with the mark needed to qualify for a major championship final these days. As seen in Figure 9, the trend for the past 15 years has been for the number of 75m-80m javelin throwers to increase, while the number eclipsing the 82.5m+ barrier on a yearly basis has remained steady.

Figure 8: This chart highlights the number of javelin throwers in each country based on the seasonal best for the year 2017.

The stagnation in producing more 82.50m javelin throwers is the part of the development process that needs to be examined more closely to see how things can be improved. In terms of performance numbers, if the top end level of performance does not improve at all during the season, then U.S. men’s javelin throwers will need to improve their execution quotients to levels above 100% to have a chance to qualify for the major international finals. In order to be in the running for medals a higher level of consistent performance that is 101-103% of the A standard is needed. At this point in time, this would mean a consistent level of performance in the 84.50-86.00 meter range. Only Tom Petranoff, Tom Pukstys, and Breaux Greer have managed this level of execution and performance with the new rules javelin. This realization turns us to the next question of how do we sent up a system and/or environment to enable this to happen.

Potential Solutions

In offering solutions it must be noted that javelin throwing is a very specialized sport. It is only contested outdoors and is vastly different from the other throwing events (shot, discus, hammer) that are often called the “heavy throws”. There is often a higher injury rate associated with high-level javelin throwing, and recovery from injuries involving the elbow, shoulder, and back can sometimes take well over a year. Because of these distinctions many head coaches in the NCAA system will steer away from putting a lot of resources into the javelin because it is felt that the risks outweigh the rewards.

To be clear, because of the specialized nature of the javelin, it will take a lot of investment to produce a high-level javelin thrower. It is obvious that the countries with the best javelin throwers do put a large amount of training capital into developing these athletes since they have the best chances to produce medals for their country (e.g. Finland, Czech Republic, & Germany). This is not the case with the U.S., which has great track and field diversity, and produces many more medals in athletics than any other country. If the U.S. would like to have any chance of winning medals on a consistent basis in the men’s javelin throw in the future, it will have to commit more resources, and have a firmer long term plan to do so.

Areas that need to be addressed are as follows:

1. Pair up the best potential javelin throwers with a top javelin coach (not a throws coach who is working with a variety of different types of throwers), and give them enough time—2-4 years—to come together and figure out the best training paths.

2. If a certain coach and athlete are successful, support them staying together and help them with what they need to be successful.

3. Make it possible to have a competitive and successful schedule at home and abroad (Europe & possibly Asia) so the throwers can prepare properly for a whole season.

This is hard to do when you are not certain when/where you will be competing. Just chasing the A standard and hoping it all works out is not a recipe for success.

Get used to throwing well on the road and in uncomfortable situations. 81m in Europe is better than 83m in Tucson.

4. Help with continuing education for the coach/athlete pairs, and give them an opportunity to visit Germany, Finland, or the Czech Republic and see what they do, what their team spirit is like, and how they see life inside and outside of athletics. The U.S. throwers/coaches can meet up at a camp/summit/or online to discuss these things and pass the knowledge on. These types of things have been done in the past but need to be done more often and systematically to become a larger part of our javelin culture.

All of these suggestions take money and support so it may not be all possible at once, but these types of measures are those that will keep us more competitive on the world stage. It appears we have the pool of athletes, but not the long-term vision and resources to be successful at the 85m+ level. Anyone of these recommendations would be a good start.