Reese Hoffa’s exceptional shot put career is detailed here. This article first appeared in New Studies in Athletics, 31:3/4, 29-37.

By Don Babbitt, University of Georgia, and Reese HOFFA, Hoffa Throws Academy.

BIOGRAPHIES

Don Babbitt is currently the Associate Head Track & Field Coach and throws coach at the University of Georgia, and has served in this role for the past 24 years. He has also been the CECS Editor for the throwing events for the IAAF since 2010. As a coach he had guided 53 athletes in major international competitions in all four throwing disciplines. These athletes have gone on to win 21 medals. The most notable of these athletes are 2004 Olympic Shot Put Champion Adam Nelson, American Javelin Record-holder Breaux Greer (91.29m), and 2007 World Outdoor Shot Put Champion, Reese Hoffa.

Reese Hoffa is currently director of the Hoffa Throws Academy in Watkinsville, Georgia. As an athlete he was 2007 IAAF World Outdoor Shot Put Champion, 2006 IAAF World Indoor Champion, and 2012 Olympic Games Bronze Medalist. In addition he earned two more silver medals at the 2004 and 2008 IAAF World Indoor Championships. He was ranked #1 in the world on four different occasions and was three-time Diamond League Champion in the shot put. His personal best is 22.43m (73’7¼”)

ABSTRACT

This article documents the entire career of the American shot putter, Reese Hoffa. A comprehensive explanation is presented of how Hoffa’s training program was developed and adjusted over the years to allow him to become one of the most accomplished shot putters of all time. In addition, a detailed account of Hoffa’s throwing improvement is presented through the course of his career along with reasons given as to why and how they happened. These descriptions and data are presented in an effort to help future coaches and athletes learn from the choices made throughout Hoffa’s career.

Hoffa’s Entire Career

Over the years, there has been abundant documentation and discussion of training programs and preparation methods for either a single season, or a major championship. However, it is rare to find an account that covers the training for the duration of an athlete’s entire career. The intention of this article is to document the complete career of Reese Hoffa, who has been one of the world’s top shot put performers for more than a decade. This will be done in an effort to help coaches and athletes see how a top level performer has navigated his career, and to explain the rationale behind the adjustments and choices made over the years in responding to injuries, changes in fitness, and an ever-changing international schedule.

The course of Hoffa’s career with the senior implement spanned from 1998 through 2016 season. During this time, Hoffa was able to achieve great success and amazingly stable results. He was ranked in the top three of Track & Field News’ world rankings for 10 consecutive years (2005-2014), while also achieving the world’s number one ranking in four of those seasons (2006, 2007, 2012, and 2014) (see table 1). Other career highlights included being crowned IAAF World Outdoor Champion in 2007, and IAAF World Indoor Champion in 2006, and winning a bronze medal at the 2012 Olympic Games. In terms of actual throwing performance, he recorded seven competitions over 22 meters, and an incredible 141 competitions over 21 meters during his career, with the latter accomplishment being the most of any shot putter in throwing history by a large margin.

The Developmental Years (1997-2001)

Hoffa’s first exposure to the 7.26kg shot came in his freshman year of university study at the age of 20 years. In high school he had thrown for 1½ years with the 5.4kg shot and had a personal best of 19.58m (64’3”) in competition using the rotational technique. It should be noted that he had warm-up and training throws in excess of 21.30m (69’10¾”) with the 5.4kg shot while in high school, so it was apparent that he had the potential to throw much further than what his competition results indicated. The critical issue that led to the instability of his high school results, and the inability to reproduce these large training and warm-up throws in competition, stemmed from the technical difficulties with his initial turn, or entry, out of the back of the ring.

The technical model, which Hoffa employed while in high school, was based of the technique of Randy Barnes and Brent Noon. This model used a “controlled fall”, as described by Brent Noon, as part of the entry out of the back of the ring while the thrower is moving through the first single support phase. Hoffa had a tough time keeping balanced during this portion of the throw, which caused him to over-rotate and land to the left of the toe board when he reached the “power position”. As Reese began his preparation for his first season with the senior implement in the fall of 1997, a technical change was made to keep the left foot continuously loaded while he performed his wind-up. This idea was borrowed from John Godina’s technique in an effort to keep him more stable over the left leg during the first double and single support phases.

This technical adjustment paid off well and Hoffa was able to throw 19.07m (62’6¾”) with the 7.26kg shot in his very first season with the heavier implement. In the subsequent three years of throwing at the collegiate level, Hoffa was able to steadily improve his best from 19.07m his freshman year to 20.22m (66’4¼”) at the end of his senior year. Apart from technical refinement, the key philosophies for improvement were to steadily increase power gains through strength & power training in harmony with technical execution, and to increase body weight while simultaneously improving vertical jump performance (see Table 1). Both of these goals were reached successfully, which facilitated the steady improvement that was seen during Hoffa’s college years.

During Hoffa’s four years of collegiate competition, the training schedule was heavily influenced by his course of academic study. As a result, throwing sessions were limited to only two times a week and were placed on Mondays and Wednesdays before lifting workouts in order to allow for maximum recovery between heavy lifting sessions. Table 2 offers a sample training cycle during the spring competition period to give an idea of the template that Hoffa would eventually use for the rest of his career. The following points were used to guide the setup of the weekly training cycles.

1. If there were no competition on the weekend, heavy squatting or leg exercises would be put on Friday to allow for a 72-hour recovery before the next training session on Monday.

2. Throwing workouts were scheduled directly before lifting workouts on Monday and Wednesdays to allow for a 48-hour recovery period after a lifting workout to recover for the next throwing workout.

3. If there was a competition on the weekend, then the squatting or heavy leg workout would be scheduled at the beginning of the week to allow for the longest possible recovery period before competition (96 to 120 hours)

4. Both competition weight shots and light shots (between 6kg-7kg) were used in training. Heavy shots were not used because they caused Hoffa to alter his technique and timing in a negative way. Heavy shots were only used for stand throws in the General Preparation Phase.

The Beginning of the Post Collegiate Years (2002-2004)

The 2002 season was the first time Hoffa’s throwing career would not be subsidized by a school/university, and Hoffa now had to rely on a $5000 post-collegiate grant from USATF and a part-time job to finance his throwing. The post-collegiate grant would be good for two years (through the 2003 season), and Hoffa had told himself that he would give himself two years to establish himself a professional shot putter. If at that point, he were not able to support himself by shot putting, he would retire and transition into another line of work. A goal of being able to throw 20.50m in competition on a consistent basis was set It was felt that this type of result would place him high in all IAAF Grand Prix events and may be good enough to get him on the US World Championship team for 2003.

Hoffa’s training schedule was kept the same as what he had done while in school since it allowed him to progress steadily. Consequently, there seemed to be no reason why it needed to be changed. As he did in his collegiate years, this schedule only had him throwing two times a week, at about 20-25 throws a session. This gave him a weekly volume of 40-50 throws, and a monthly volume of around 220 throws. Compared with most world-class throwers, this throwing volume was very low. What was important for Hoffa, however, was that the quality was very high, so there was a sharp focus on execution of movement, and the sessions were completed before any significant fatigue could affect technical execution. It was felt that this training approach would reduce the long-term wear and tear on Hoffa’s body and would pay off for him by allowing him to produce world-class results well into his 30’s.

In his second year out of college, Hoffa was able to put together a solid season with 11 meets over 20 meters and six meets over the 20.50m (67’3¼”) mark. He reached his goal of making the 2003 World Championship team in Paris and won the gold medal at the Pan-American Games while throwing a meet record of 20.95 (68’8¾”). These results were critical, and enabled Hoffa to make enough money—and secure a shoe sponsorship—to continue his throwing career.

After the 2003 season was complete, the competition results were analyzed, and it was determined that even though Hoffa had reached his goal of throwing well enough to now be a full-time shot putter, the average meet results were still too inconsistent with large fluctuations in performance. On two occasions in 2003, Hoffa had important throws land just outside the left sector due to over-rotation caused by turning out of the back on his left heel. The first was a 21.34m (70’¼”)sector foul at the Mt. SAC Relays, and the second was a 20.30m (66’7¼”) sector foul in the World Championships qualifying round in Paris. Both of these results would have drastically altered his ranking and status in 2003 if they had landed just 30cm to the right and in the sector.

To address this issue, it was determined that Hoffa should “stay in touch” with his timing and technique so he would not have to spend a lot of time trying to find or retool it during the course of the competition season. This would be accomplished by throwing year round. It was decided that during the off-season (from September to November), that Hoffa would take 10 full throws one time a week to maintain a good throwing pattern, so he would not have to find his timing as he began his General Preparation Period for the next season at the beginning of November.

During the fall throwing, Hoffa was able to throw consistently over 20 meters and at times could hit 20.50-20.60m. This was done without any formal conditioning program at the time. The only technical focus during this two-month period was to work on staying on the ball of the left foot as he turned out the back of the ring. Hoffa was starting to develop a tendency to roll back on his left heel as he turned out of the back of the ring, which caused him to do a “heel turn” instead of the traditional pivot on the ball of the foot. By cleaning up the turn out of the back of the ring, we felt that Hoffa would be more consistent in reaching the middle of the ring and reduce his tendency to over-rotate when he tried to go fast.

The tactic of not taking a break from throwing during the fall worked out very well, and Hoffa was able to throw a large indoor personal best of 20.29m (66’7”) in early December of 2003. He transitioned well into the indoor season breaking 21m for the first time and finished the 2004 indoor campaign by winning a silver medal at the IAAF World Indoor Championships in Budapest, Hungary with a personal best of 21.07m (69’1½”). The overall focus during these first few post collegiate years was to (1) have steady improvement in performance and (2) to reduce the number of poor performances. By the 2004 season, it was very rare to see Hoffa throw below 20 meters in a competition. This type of consistency enabled him to achieve his first top-5 world ranking in 2004, as well as making the first of three US Olympic Teams.

One development that came out of Hoffa’s experience at the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens, Greece, was a new and more focused effort in the approach to qualifying rounds. Hoffa was not able to get out of the qualifying round in Athens, posting a mark of only 19.40m (63’7¾”), and was mistakenly only given one warm-up throw in the stadium. As a result, a change was made in throwing sessions leading up to major competitions, where a throw of 20m must be reached after only three full throws in any session. This philosophy would be followed for the rest of Hoffa’s career, and he was able to successfully qualify in all subsequent major championships on his first throw in all but three competitions (where he utilized all three attempts).

The Prime Years (2005-2012)

The years spanning from 2005 to 2012 were the most successful of Hoffa’s career. During these years he was ranked no worse than #3 in the world, and finished ranked #1 in the world for the 2006, 2007, and 2012 seasons. Going into the 2005 season Hoffa had developed his power levels in the weight room and in field tests to where we thought he was capable of 22 meters (72’2”), provided he could execute his throw with good technique. It was felt that a throw of 22 meters would be good enough to win any major championship at this point, which is why it was chosen as the performance target.

At the same time, a choice was made to take the snatch out of his training program in an effort to protect a tender back that Hoffa had developed in the 2004 season. By the end of the 2006 season, both the push press and clean were also taken out of the program as well for the same reason. There was an initial fear that 22 meters could not be reached without having such powerful exercises remain in the program, but these fears were quickly allayed as the training results continued to improve, even after their omission. Careful attention continued to be paid to the relationship between Hoffa’s bodyweight and vertical jump as well. Each successive year of training saw him gradually gain weight along with either maintaining or improving his vertical jump at the same time. For example, in 2002, Hoffa had a bodyweight of 130kg (287lb.) and a 71cm vertical jump, which then improved to a 75cm vertical jump at 137kg (302lb.) bodyweight in 2006.

By the time the 2006 season was complete it had become a very rare occurrence for Hoffa to throw below 21 meters in a competition. This was a testament to his ability to maintain a good throwing rhythm for the whole year. A key strategy was developed for maintaining the throwing rhythm by matching up the weight of the implement thrown in training to the fatigue level seen at the time. The choice of shots for training during the outdoor competition cycle was centered on the ability to maintain a good rhythm and throw between 21.00-21.50m in training. In order to do this, Hoffa would throw a 6.6kg shot when he was feeling very fatigued, such as when he returned to the US from a series of competitions overseas. The 6.6kg shot allowed him the possibility to achieve his target distance and intensity. After a few sessions, once his nervous system recovered from the trip, he would switch up to a 7kg shot. Finally, in the last few workouts before the next trip, Hoffa would throw the 7.26kg shot. This progressive approach allowed him to always stay in his throwing rhythm for his target performance of 21+ meters.

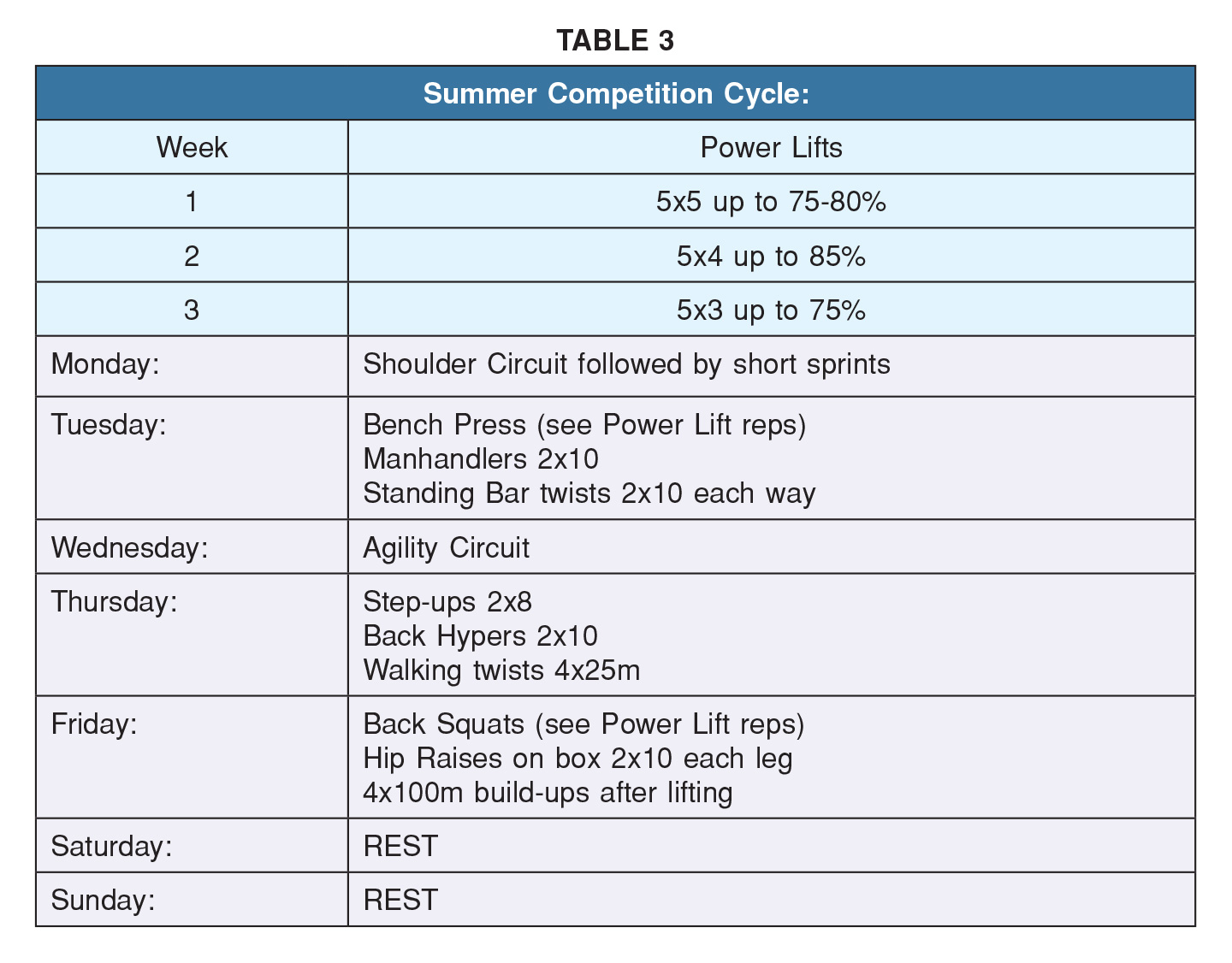

During the months of May until September of each year, the overwhelming majority of Hoffa’s competitions would be held outside the United States. This necessitated the need for a training approach during this time that allowed him to (1) maintain his throwing rhythm, (2) maintain his power levels, while still being able to recover from the international travel that most of his competitions required. Table 3 provides a description of a three-week training cycle that Hoffa would use in between in series of international competitions that allowed him to maintain his form. This type of cycle would be repeated over and over between his international trips.

With these training principles fully developed by the 2006 season, performance plan for the following years remained largely intact from year to year. The quality results were reproducible each of the following seasons with only minor changes being made to work around injuries that would pop up from time to time, as was the case in the 2009-2010 season.

The Final Years (2013-2016)

Following the 2012 London Olympics, Hoffa developed a nagging injury to his left knee. This injury stayed around for most of the 2013 season and caused him to make some inadvertent changes to his technique as he entered out of the back of the ring. The instability in the start out of the back of the ring caused him to have the shortest seasonal best performance since the 2004 season; however, he was still able to compete well and earn a #3 world ranking at the end of the season. The 2014 season saw Hoffa return to full health and he was able to find steady form, win the Diamond League, and finish the year ranked #1 in the world.

Hoffa’s plan at this stage was to finish his competitive career at the end of the 2016 season. Efforts were focused in these last two years to limit the number of competitions and avoid excessive travel in order to maximize recovery and conserve energy. These adjustments were relatively successful in 2015; however, it was becoming an ever-greater challenge to determine how much recovery Hoffa needed between competitions and travel. In 2015 and 2016 it took about twice as many days for Hoffa to recover from a trip than it did before 2014. It became apparent after many years of training that it was relatively simple to figure out how much to work to put in to reach a given level of throwing fitness, but it was a constant battle to figure out the amount of recovery that was needed between training and competition.

Upon reflection after the conclusion of the 2016 season, Hoffa felt that his move to start the Hoffa Throws Academy in 2014 actually affected his training, and thus, his performances from 2014-2016. During those seasons it seemed a little harder him to feel completely prepared for the top competitions, but he was not quite sure why. This epiphany, made it clear that splitting off, just a little of his time, to begin the building of his academy, took away from some of the little details involving recovery, that allowed him to be at such a high level for so long. Such realization happened too late to have any effect on Hoffa’s results, but it did serve as a valuable lesson for future use as an aspiring coach.

Reese Hoffa Sequence