COORDINATED BY RUSS EBBETS

Editor Russ Ebbets gathered an A-list of sprint relay coaches and experts and plays 20 questions with them.

THE PANEL: Glenroy Gilbert was an outstanding sprinter at LSU and for Team Canada, where he earned gold medals as part of the Canadian 4×1 team at the 1996 Olympics and the 1995 and 1997 World Championships. Since 1996 he has worked with Athletics Canada, primarily as coach of the Canadian men’s and women’s relay teams. In 2017, he was named Athletics Canada’s permanent head coach. Gilbert is answering these questions in conjunction with Dana Way, MSc, a biomechanist with Athletics Canada for more than 15 years, with a primary focus on the relay programs where he analyzes race strategy and exchange technique (GG and DW). Junior Burnett is in his tenth season as assistant coach for sprints, University of Albany. In 2017 he was a nominee for the USTFCCCA Northeast Assistant Coach of the Year. He has coached nine NCAA first round qualifiers and produced 33 America East sprint champions. He is Level 2 Certified in sprints, hurdles and relays (JB). Caryl Smith Gilbert is currently director of men’s and women’s track & field at the University of Georgia. Prior to Georgia she was the head coach at the University of Southern California, where her women’s teams won the 2018 and 2021 NCAA outdoor team championships; she was National Women’s Coach of the Year both of those years. She also led the men’s programs to top five NCAA outdoor finishes in 2014, 2015, 2018, and 2021. A UCLA graduate, she was a three-time All-American in the 100m, 4×100, and 4×400 (CSG). Brooks Johnson was a member of the gold medal-winning U.S. team at the Pan Am Games in 1963. Johnson has coached at the University of Florida, Stanford University (succeeding Payton Jordan), and Cal Poly. He was part of the Olympic coaching staff in 1976, 1984 (women’s team coach), 2004 and 2008. He still coaches individual athletes (BJ). Dennis Grady is a certified Level 2 coach in sprints, hurdles and relays. He was a long-time high school coach in the Columbus, OH area, his 4×100 teams winning two Ohio state boys’ titles. He was most recently a volunteer coach at the U.S. Naval Academy. He has published ten articles in Track Coach, specifically on the 4×100 relay (DG).

The fly zones are gone, how many steps does it take to get up to full speed for the outgoing runner?

CSG — Well… for the women 25-28 and for the men 27-31 steps will work. Keeping in mind that the speed of the incoming runner and the acceleration experience of the outgoing runner still affect the number of steps, so there is really no set amount in theory.

GG and DW — The outgoing runner won’t reach top speed within the zone as that normally happens after 50m. However, most athletes can get up to 80% of top speed near the end of the zone. In terms of steps, that is dependent on the athletes’ stride length during their acceleration pattern.

DG — The outgoing runner will not reach maximum speed before receiving the baton. If the plan is to exchange deep in the zone, 25-27 meters in, the outgoing runner is likely at 80-85 % and still accelerating. I base that on an analysis of Usain Bolt’s 100m World Record. With the aid of starting blocks Bolt reached 82% max velocity at 20 meters. He did not reach 99% until 40 meters.

JB — An outgoing runner needs anywhere between 11-13 steps to get to top speed for a smooth and clean exchange. This number of steps is ideal for both runners to match speed in the last third of the 30 meters zone.

BJ — Outgoing runner cannot reach maximum speed within the exchange zone.

Coaching Ed has long taught right-left-right for the baton exchange pattern – why is that?

JB — Right-left-right pattern allows for best transition of baton from one runner to the other. Also, for safety and preventing of serious injuries while moving at maximum speed. The baton can only get around the track smoothly if its passes in this pattern “right-left-right,” since runners share a confined space during the exchanges, and they are moving at high velocity. Safety and logistics are my reasons.

DG — The R-L-R-L hand pattern keeps the baton in the middle of the lane out of harm’s way. Legs 1 and 3 (on the curve) favor the inside of the lane; leg’s 2 and 4 (straightaway) favor the outside. This alignment keeps feet, legs, and arms from unwanted contact.

BJ — Left hand keeps baton closest to inside the curve.

CSG — First leg runs on the inside of the lane, 2nd on the outside, 3rd on the inside, and 4th on the outside. So, when you alternate hands, it makes for a smoother transition from hand to hand. Also, this keeps the first and third runner running on the inside of the lane with the baton in their right hand and the second and fourth runner on the run on the outside of the lane with the baton in the left hand.

GG and DW — Well, if it were left-right-left, the corner runners would have to run on the outside of the lane. It is much more efficient to run on the inside of the lane

Do you prefer the underhand or overhand pass? Why that choice?

BJ — Overhand because of easier sight line to inside of hand.

GG and DW — Neither. The Push pass is the preferred method in Canada. We believe it promotes a more controlled pass (less reaching) compared to overhand. We also believe that it gives you “free distance” when compared to the underhand or upsweep pass. A secondary downfall to the upswing pass is that it is often passed to the receiving runner in the middle of the baton. This will not leave much room for the next runner without repositioning the baton while running.

CSG — I personally prefer the overhand pass because if you have a good target and a high hand all the incoming runner has to do is “push” the baton into the outgoing runners hand.

JB — I personally prefer the overhand pass. I like the overhand pass better because of its practical nature and resemblance of the running action. The runners don’t need to make much mechanical or technical change during sprinting to execute this pass. If taught properly the runners don’t need to change their top speed mechanics for this pass.

DG — I prefer the overhand pass — but not really a “push technique” — with the receiver’s arm extended back with the palm up and a V-target. Keeping his normal arm swing the passer extends his arm and flicks his wrist placing the stick in the V of the hand. The underhand pass requires the runners to be closer together and takes more time. BTW, how did the Japanese men’s team fare in Tokyo?

What should be the thought of the outgoing sprinter regarding the baton exchange? (i.e. – hold hand still, give a big target, etc.)

CSG — The outgoing runner should be thinking about literally leaving the incoming runner. Also, they should be thinking about putting their hand back halfway through the zone for a silent pass or listening for the call if they’re using a verbal command pass. If they’re halfway through the zone and they don’t have the stick then slow down and put your hand back and wait, the incoming runner’s job is to make sure he/she gets the baton to the outgoing runner.

DG — First and foremost the outgoing sprinter should be relaxed: confident that the marks are good, and focused on the incoming runner — leaving when he hits your “Go” mark. 2) Accelerate as fast as you can — make the incoming runner catch you! To keep relaxed and have the best sight line to the Go Mark, I prefer the two-point stance for the outgoing runner. (Note: Italy’s men’s OG Gold medal team, #3 runner used 2-pt stance and the exchange could not have been better!)

BJ — Give as large and steady a target as possible.

JB — The outgoing sprinter should give the incoming sprinter the biggest target possible and hold his/her hand still. Should be patient through the zone, be aggressive, relax and not worry about the end of the zone (trust). The bigger and sturdier hand gives the incoming sprinter the best chance for clean and smooth baton exchange. Relays (4×100) are won not only due to speed, but due to excellent exchanges. (Hard to hit a moving target.)

GG and DW — Thoughts will be dependent on the strengths and weakness of each athlete. If an athlete struggles with one aspect, then that portion will be re-cued. Generally, the sequence is, wait until the incoming runner is at the “go mark” (leave on time), accelerate hard, hear the cue “High”, lead with the elbow, give a firm target and steady hand. Sometimes athletes need simple reminders on one of these steps.

What do you recommend as the thoughts for the incoming runner?

BJ — Focus on “V” of outgoing runner’s hand.

GG and DW — Again, this is dependent on the individual. Often the messaging is, SEE the target then make the pass, run THROUGH the outgoing runner, not TO the outgoing runner.

DG — Attack the Zone! Call stick when you are ready, but do not reach at the same time you call stick. Be patient wait for the target and firmly place the baton into the V. Stay in your lane until all traffic clears.

JB — I need my incoming runner to remain aggressive, maintain great sprint posture and mechanics, while relaxed. Don’t get too excited early, but concentrate on sprint technique early, midway and late. Attack the last 40 meters once inside the zone, try to outrun the outgoing runner. Run an extra 20-30 meters after the exchange. (Helps with deceleration.)

CSG — The incoming runner should literally be thinking about running over the outgoing runner. Also, one item of importance is to run past the end of the relay zone. This will ensure that if any mistakes are made the baton can still get to the outgoing runner.

If you are in a high school or collegiate coaching situation how much time is spent weekly practicing relay exchange work?

GG and DW — Anytime you can get your hands on a baton is a good thing, especially at these levels. Even when you don’t have a dedicated relay practice scheduled you can incorporate baton drills in a warmup very easily. Building a solid foundation of relay skills at an early age is extremely beneficial. When it comes to choosing a team in Canada, relay specific skills and knowledge are major factors.

JB — I conduct relay practice 3 times weekly in season. I break down each session to a specific skill: zone running/handoff, zone exchange focus on top speed exchanges 3-5 per session, and standing static drills. Teaching basic hand drills and blind passes. All have their place in my training plan based on athlete knowledge and level of development.

DG — Sticks and Starts are the day before competition practice. The Baton practice is fairly quick: All four runners are present at each zone as we walk around the track. While the two involved practice, the other two are watching to 1) make sure the outgoing runner leaves on time; and 2) see where the actual pass occurs. We move on to the next zone when all four are satisfied that that exchange is good. (Time: 35-45 minutes)

CSG — During an average outdoor season we spend about 1 to 2 days a week working on relay passes.

BJ — At least once a week.

Do you have your sprinters do any of their track work carrying a baton?

DG — Besides the lead-off runner practicing starts with the baton, No. Unlike the football running back prone to fumbling the ball, our sprinters know there is no reason for the baton to ever be dropped. The passer makes sure the baton is secured.

CSG — I personally do not make a practice of having sprinters do track work with a baton but it is very feasible and probably a good idea for someone who may be inexperienced to carry the baton or do starts with the baton.

GG and DW — At this level it’s highly unlikely they will and if they do, its usually only the starts for someone that might be running first leg.

BJ — As much as possible.

JB — I never did this with my sprinters before. They ran with baton during their warmup jog, helping hand placement and confidence. I also heard of quarter-milers carrying the baton during 400m workouts as they tend to be more relaxed running the 4×400 relay than the open 400. As some 400 runners are better at the relay than the individual race, carrying a baton during workouts tend to narrow the relaxation gap between both events.

How many strides can or should a relay runner be expected to hold the exchange position – running with the back arm elbow extended?

CSG — The goal is for the outgoing runner to run as few steps as possible with their hand extended. So that’s why it’s important to have the proper amount of steps because you want to keep the baton moving as fast as possible through the zone.

GG and DW — In order to have an efficient exchange, you ultimately need to minimize the amount of time the outgoing runner has their hand back. The longer the athlete has his hand back, the more problems arise; they will begin to decelerate, the extended arm will start to sway and they will most likely panic and look back. If you were to give it a number, I’d say two strides would be an efficient pass, but you have to be able to hold that position for up to 5/6 strides.

BJ — Hold the hand available until exit from zone or receiving the baton.

DG — If the timing is right and the exchange is performed well, the arm swing should be normal and the pass is made in one stride. As a general rule the more strides taken with the arm extended, the less likely you will have a good exchange. (See U.S. men Tokyo Olympic prelims)

JB — I say anywhere from 2-4 strides, with two the minimum, for a very quick exchange. This requires lots of precision and drilling at high speed. The more time spent with elbow in extension the more deceleration can occur in the zone (slowing down the baton). Two to four stride requires lots of top end speed exchanges in the zone and lots of film reviews.

For the outgoing runner’s receiving hand, do you recommend a “soft” hand that allows the infantile grasp reflex to be naturally activated (when something hits the palm the fingers flex closed) or do you recommend a stiffer hand that closes with the slap of the baton?

BJ — The soft hand to cause grasp reflex until baton is exchanged.

JB — I recommend the stiffer hand option, because I prefer a big and still target. This also has other benefits too like a chance for a much quicker exchange.

DG — The former with the palm up, V-shaped target: the stick placed in the web of the thumb joint. Some muscle-bound sprinters have less range in extending the arm back and modify the target with the “chicken wing” out to the side, flat hand with thumb down, and the baton is pushed into the target. That is the technique used by the U.S. men’s national team. Judge for yourself by their results.

CSG — I prefer that the outgoing runner puts the arm back from the shoulder leading with the elbow with the thumb down and the four fingers closed and I prefer the incoming runner to push the button into the middle of the palm so the fingers close naturally.

GG and DW — I think it’s a bit of both, maybe leaning on the stiffer side. You want to have a firm target so that when the baton is pushed into the hand it wants to close around it. If the hand is too soft, the athlete will tend to start searching for the baton once it initially touches the hand.

Is not one of the problems with the short relay the lack of opportunities? As more money has come into the sport and the top athletes have opted for an “early out” or skipping college altogether – has this not contributed to a lack of competitive career experience in the sprint relays past high school?

GG and DW -— Lack of opportunities at the top level can certainly be a problem especially in North America. We in Canada try to expose our athletes to as many opportunities as possible through yearly camps and relay specific events. Running relays in college can be a huge advantage to runners as they are generally exposed to multiple sports and a lot of races. However, it can be a disadvantage at times when the athlete tries to adapt to our Canadian system. This is not usually the case though.

BJ — Generally sprinters have been working baton throughout their total career.

CSG — I do not believe the short relay has any lack of opportunities. We coach the student athletes that are on our team the best we can and for those who decide to go pro early we just don’t get to coach them. I believe college track and field gives every student athlete a great deal of experience of being able to run all four relay legs and teaches them to know what the zones mean through repetitive races.

DG — I think it is more that the relays are not that important for the pros; the individual events are by far the priority. Russ, your two-part roundtable in previous Track Coach issues about the relays of Coach Elliott of Villanova at the Penn Relays shows the importance of relays at the high school and collegiate levels.

What about the influence of private coaches, shoe companies, agents, parents and personal agendas (initiative clauses) and their effect on national team relay selection and even which leg to run?

BJ — Outside influence is usually minimal, especially at elite level.

GG and DW — This is a good question; I tend to think this might be a primarily U.S. team issue. That is certainly not to say other countries don’t have their share of issues in this area but the nature of the U.S. system and the fact that the U.S. has the best track and field athletes in the world who have enormous contracts and incentives for medals at the World and Olympics games creates these types of problems. There is lot of pressure by all the entities above for athletes to run and to run in certain positions on the track which I feel is the root cause all the problems that ails in particular the U.S. men’s short relay.

JB — Surely, I see that as one of contributor that causes lack of competitiveness in the short relay at the international level (especially men’s relays). Skipping college has lot to do with athletes’ unpreparedness and lack of knowledge in the sprint relay. There is so much to learn in college that you cannot gain at relay camp for 2-4 weeks before major championships and Olympic Games. Many of the mistakes and underdeveloped skill can be worked on during college competitions/college years.

CSG — When it comes to national team selection of course everyone has their own biased opinion about what is preferred. However, if an athlete knows how to run all four legs then that eliminates any confusion and cuts down on limitations that will be placed on that athlete.

DG — I have been watching the national relays intensely for 15 plus years and I see little consistency on 4×1 selections. The most common process is “self-selected”, meaning the first-four finishers in the 100m are the de facto members for the next global championships 4×1’s. World Athletics rules for the 4×1 relay are not conducive for well-prepared relays. WA’s focus is saving a few dollars by limiting the size of a country’s team.

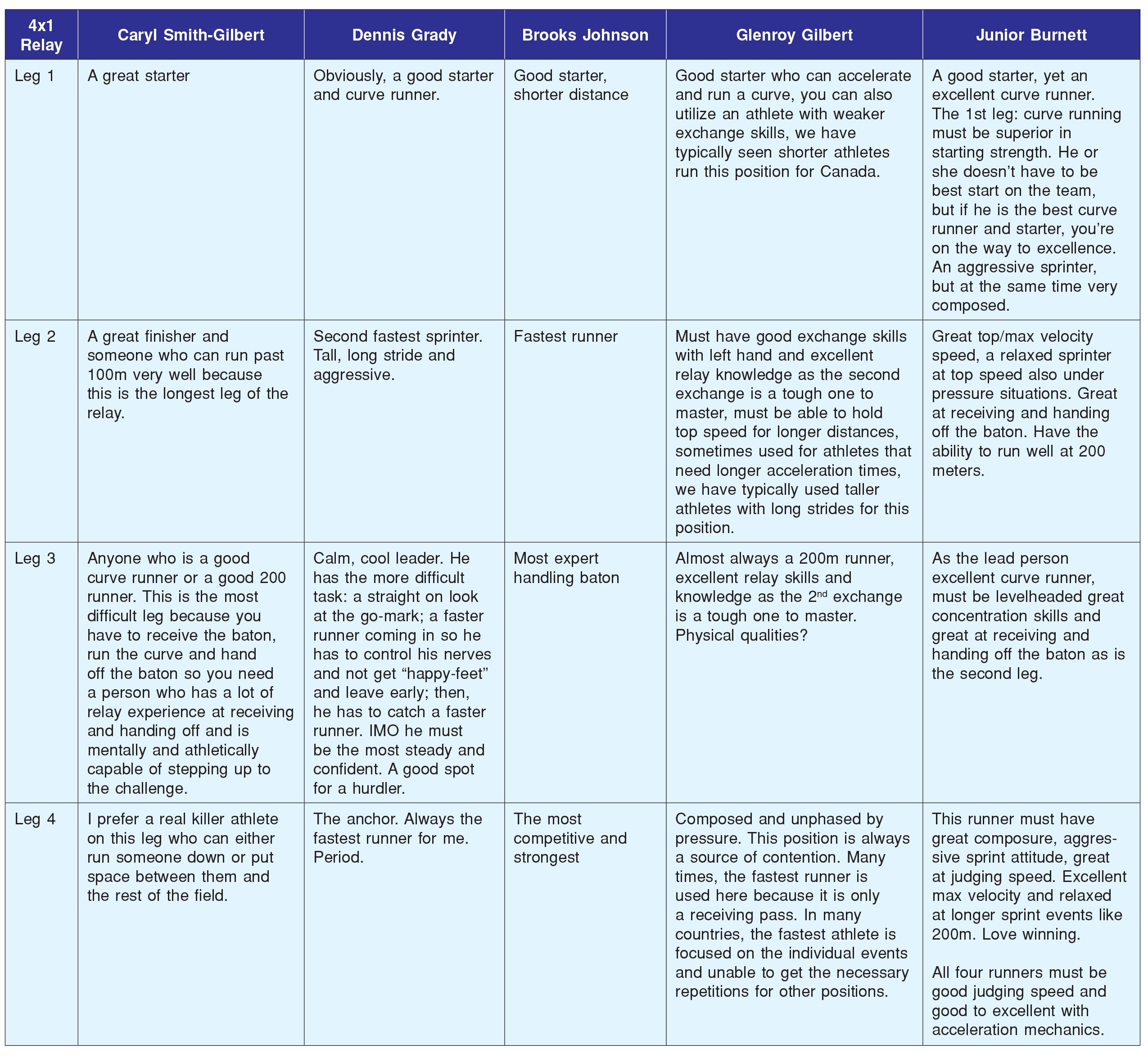

Run down the four relay legs for me. What are the preeminent skills or physical qualities you see as ideal for a relay runner in that particular slot?

Each answer is presented in the chart below.

How does one correctly hold the baton while running. Does the grip change while one is making the pass?

GG and DW — In a push pass, if the pass is completed properly, the athlete should receive the baton on the top third not the middle. The baton is received in the palm and fingers wrap around with grip that is tight but not strained. This will reduce the chance of having to “fiddle” with the baton in attempt to give the next athlete more baton to work with. It should be set up so that when giving the baton it is just an extension of the arm during the stride.

CSG — The baton should be held at the bottom and hand off the top which makes it be at the bottom for the next person. You never change hands in the relay or you risk slowing the baton down in the zone therefore slowing down the relay time overall.

JB — The correct way holding onto the baton is at the lower third. When done correctly the runners have no need to adjust while running or during exchanges. If the situation occurs and he or she have to adjust while running down the track, it’s best to make the adjustment before the exchange comes up. It’s always very risky adjusting the baton during the exchange, high risk and low-rewarding.

DG — The baton must be shared. The passer holds the bottom half and the receiver gets the top half, which becomes the bottom half as his arm swings forward. The grip should not change for the overhand pass. (Note: the underhand pass has each hand moving up the stick. By the time the anchor gets the baton his hand is at the top of the baton.)

BJ — Holding close to end leaving space for outgoing hand.

Ideally what part of the zone should the relay baton be passed? Does this change with the different legs?

JB — In a perfect world, the baton would be best passed two to three steps after the middle of the zone. I like to see it done at 2 steps after the middle: for the outgoing runner about 23 -25 meters. You must drill these exchanges well in order to execute them in competition and be successful at it. No need for changing the distance except if you are working with a slower runner.

BJ – This is individualized to incoming and outgoing (sprinter’s) speed and strength.

CSG — I personally prefer the baton to be passed before the middle of the zone. However sometimes your personnel can determine where you want the baton to be passed in the zone. Meaning I might want someone to get the baton early in the zone because I know he can run a good leg for me and I prefer for him to have the baton longer versus someone who I prefer to run a shorter leg.

DG — The deeper the better: that is where the speeds of both runners are closest to being equal. It does change, especially at the high school level as mentioned before when trying to extend the distance your fastest runners have the baton in their hands. (On 4×200 relays, the opportunity to extend a specific leg is huge)

GG and DW — It is well established that, if done correctly, the further in the zone you pass, the faster the exchange will be. In Canada we strive to pass anywhere after the scratch line. It should not change with respect to different legs, however, depending on the situation, the second exchange can be adjusted based on the lane. This is done because the baton is exchanged on the curve and depending on the lane, it will be more or less difficult depending on the “tightness” of the curve.

How much consideration do you give the deceleration pattern (from 60m to end of the relay leg) of the individual relay legs? Is there a different concern for the turn runners (#’s 1, 3) versus #2 on the back straight?

GG and DW — The deceleration pattern is considered based on the individual athlete’s current fitness, how many races they have run, what lane they are in and of course the position that they are running. If a runner is on an inside vs outside lane he will most certainly decelerate differently. In terms of position, the corner runners will typically decelerate more as well.

DG — Comparing each of the four legs to what you have in the open 100m is natural. But the only leg using blocks is #1. The acceleration pattern without blocks will change somewhat. Could not the deceleration pattern also differ? I coach “Attack the Zone”, so my answer is none. The placement of the “Go mark” has accounted for the slight deceleration at the end of the 120 m run.

JB — I don’t give much consideration to deceleration for the sprint relay. I consider the first leg runner and second runner to a lesser extent. If the runners are in the correct order and practice the correct specificity for each leg deceleration will not happen. However, in particuliar situations the second leg can run extra distance and might run into deceleration. Specific training can fix this.

CSG — It is very important for each incoming runner to run past the end of the zone so I don’t talk much about the deceleration pattern from 60m to the end.

BJ — This needs attention and individualization.

Do you recommend any change in sprint mechanics when running the turn? (i.e. – inside arm drops back, outside arm crosses over, etc.) –

DG — Yes, and we practice running curves to focus on these sprint mechanics along with solid “front-side” mechanics as taught at the USATF Level II school. In addition to the arm swing adjustments, I recall one instructor emphasizing the lean starting from the inside ankle. Turn running can be improved, no question.

GG and DW — At this level we typically do not coach any running mechanics without discussing with the personal coach.

CSG — The turn should be run the same as you run the turn in the 200 keeping in mind you have to stay close to the inside with the baton in the right hand since you are handing off to the fourth leg who will be on the outside of the lane taking the baton in the left hand.

JB — No, I don’t recommend sprinters changing their sprint mechanics for the turn. I recommend and encourage them to maximize centrifugal force on the turn. Their posture remains the same as sprinting down the straightaway; the only thing that changes is their foot placement on the ground. They touch down inside out on the turn. The sprinter’s inside foot touches down outside of the line where the outside foot touches down. This creates a natural lean from the athlete’s ankle joint through to the head. Just run through the turn with normal sprint mechanics as down the straightaway.

Do you prefer a verbal or sight start cue for the relay exchanges? Why?

BJ — Exchange based on number of strides preferable to verbal commands

GG and DW — In Canada we use a sight cue to initiate acceleration and a verbal cue to initiate the actual exchange. With relays, you try to limit the variables that can go wrong. The outgoing runner will react to the incoming runner as they reach the “go mark”. By doing this, we limit what the incoming runner’s responsibilities are and get rid of the guess work. The incoming runner can focus solely on the outgoing runners’ acceleration and use the verbal cue of “High” to initiate the exchange.

JB — I prefer the sight start cue for relay exchanges. It presents multiple opportunities and challenges for runners to learn and develop new skills other than just sprinting around a turn or down a straightaway. This technique can foster discipline and trust for both the incoming and outgoing runner. They can learn to judge distance, speed and coordination.

DG — Verbal. The 4×1 exchange is a “blind” exchange because the receiver does not look back for the baton (as with the 4×4 exchange). The passer is in control of the timing, he sees when he is in position to pass, he calls “stick”, he waits for the target to appear and puts the baton into the hand — letting go of the baton when the fingers close. Fast, efficient, sure and in one stride.

CSG — I prefer a sight start cue because when there’s a lot of traffic and a lot of voices, confusion can take over. However, for someone who may have trouble visually seeing the marks clearly, I will use a verbal start cue to be sure we get the steps done properly.

What are some teams both nationally or internationally that routinely produce excellent relay racers? (you can reference high school, college or international)

CSG — There are several teams that routinely produce excellent relays. But from year to year it changes.

GG and DW — If you asked this question 10 years ago it would likely only be a handful. Now there are so many teams and countries that produce excellent relay runners. Obviously in Canada we pride ourselves on producing good relay teams. Some countries that have been very consistent in terms of relay skills over the years include Japan, Brazil and France. In terms of the collegiate system, there are a lot of great relay programs and we have seen a lot of good relay runners from the SEC (LSU, Texas A&M, etc.) and some Pac-12 (USC).

BJ — America—club, school, college.

DG — Russ, I am afraid my only contribution here would be to plug high schools I have coached to state 4×1 relay championships and The U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis.

JB — Firstly, on the high school teams, Jamaica has excellent relays teams; Calabar boys, and Edwin Allen High girls. Colleges: Florida men, LSU men and women and Texas A&M women consistently produce great sprint relays. International-—Jamaica women, USA women and Great Britain women have been the most consistent over the years, advantage to USA. Jamaica men over the Usain Bolt era. The men dominated for long time, but not recently.

The whole “interchangeable parts” idea with the U.S. national team relays doesn’t seem to work very well. Do other national teams do this? I understand the thought to spread the wealth and “save” the best for the last race, but it doesn’t always work out that way. Is the main concern injuries, ego or giving the upcoming talent experience or some combination?

DG — To the best of my knowledge, no other national teams use substitutes for the 4×1 relays as much as the US does. For the three 4×4 relays interchange all you want! The main concern is more medals and a paycheck for the subs. The more-the-merrier approach for the U.S. is SOP. Jamaica is the only other country that freely substitutes legs for their 4×1’s. In the Tokyo Olympic men’s 4×1 final no teams used a substitute in the qualifying.

CSG — I am not certain what other national teams do. I just know with my team I prefer to keep the relays the same as much as possible because the more we hand off with the same order the faster we become and we don’t have to keep reinventing the wheel in terms of finding out what steps are best for each person. The U.S. team has an interesting dilemma every year because anytime you don’t have people that practice together at the same time all the time you’re going have to make decisions at the last minute and it’s a tough situation.

BJ — Personnel on team determine tactics.

GG and DW — A lot of countries do not have the talent that the USA has in terms of sprinting, so this doesn’t necessarily come in to play. Changing the order of athletes just to give someone else a chance can be a risky play. However, with the relay, things ultimately come up and throw a wrench in your plans, whether that’s individual athletes competing right up until the relay, injuries, or something totally out of the blue. If we feel we need to make a significant change in the relay, we will do an analysis of how the change will affect the race as a whole and at each zone. If the benefit outweighs the cost, then we will make the change. In Canada we always try to have Plan A, B, C and sometimes D.

JB — Very good question; yes, I think teams change personnel, so I don’t think that’s the only problem to the equation. The bigger problem is lack of training time with teammates. When you have people from four training camps coming together in the greatest pressure situation, mistakes happen. Look at the world record Jamaica team; runners from two training camps made up the team: lead off to second practice at the same place and third to fourth at same camp. So, familiarity and cohesiveness were there. They bridge the gap between second and third and they are good. So I think geography and time spent practicing is more of a problem than “interchangeable parts.”

In a perfect world what would be your recommendation for creating an unbeatable 4×1 relay team?

GG and DW — This is a bit of a double-edged sword. If you have a team that consistently trains with each other, you lose out on the individuals getting faster by competing individually. If you have a team of incredibly fast athletes, they will be unavailable to train relays as they will have other commitments. I think that having an adaptable program that is built on solid relay foundations will ultimately serve you the best.

BJ — Get the four fastest runners who are comfortable with each other.

JB — In a perfect world, it’s the four fastest humans. Not so easy though. You must select the four best runners/sprinters and place them according to their strengths and at times strategize to beat your main opponent. In a nutshell you must have each runner in correct order. Coleman, Ronnie B., Fred K., and Noah L. These four can be unbeatable. Find the best way to maximize each runner and legs.

DG — Sweep the 100m final, maybe have 2 or 3 current and former 100m world record holders on hand; run two or three practice competitions; adjust the “go marks” as needed (necessity is the mother of extension); have a nice dinner together the night before; and Viola! An Unbeatable 4×1 Relay! But only if they execute.

Are there any drills or video references you are particularly fond of?

GG and DW — In Canada we really try to keep it simple- We focus on the basic fundamentals of relay running and try not to deviate from basic principles; so we have always use Gerard Mach’s basic approach.

DG — In all honesty, I am not big on drills, especially the drill with the runners standing still and swinging their arms in unison and tapping the hand several times. Or the jogging around the track, all four in a row passing the stick in slow motion. In Track Coach #174, readers can find my favorite drill for big-meet preparation. As I explained earlier the best practice is doing the exchanges full speed with all four runners participating.

JB — I like blindfold seated and standing exchanges. Helps with trusting and judging the hand placement.

BJ — Warm up and warm down with athletes exchanging baton with as much precision as they can muster.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

GG — I think that one of the main reasons that Canada has been successful as a country in the relays is that we have a solid relay program that has adapted and evolved over the years. I think we excel at mixing sport science and the art of coaching very well and one does not outshine the other.

DG — How difficult is a 4×1 exchange? Slightly more difficult than a handshake and about the same degree of difficulty as a PAT in football. I want to thank USATF Coaching Education for the excellent instruction and schools they provided. And finally, Russ, thank you for another fine Roundtable discussion!

JB — Relay runners must be aggressive in nature and have a special love of winning, must be able to take chances at pushing the exchange barrier, can’t stay in the comfort zone if they expect to win the 4×100 relay. Coaches must teach relay runners to live on the edge of running away from the incoming runner.

DENNIS GRADY’S HINTS FOR 4X100 SUCCESS

LAWS GOVERNING RELAY EXCHANGES

1) Never leave the zone without it. Just because an exchange isn’t perfect is no reason to give up on it. The outgoing runner, nearing the end of the exchange zone without receiving the baton, should open up, turn around and look for the baton, slowing up, if necessary. A poor exchange beats no exchange.

2) Always finish the race. If the baton is dropped, pick it up! Don’t just stand there and argue about who is to blame. And don’t disqualify yourself because you think you were out of the zone. If the “stick” is in the zone, the pass is legal. Let the officials do their job; your job is to finish the race. Stick to it! DNF (Did not Finish) usually means “you quit!”

3) Timing is really everything. We are talking hundredths of a second. Don’t fall asleep at the switch by leaving too late; don’t jump the gun by leaving too early. Coaches may debate which is worse. I side with the leaving late. With Law #1 firmly in mind, a runner leaving early can salvage the race. On the other hand, if a runner leaves late, the time lost is gone for good.

4) Grady’s Law: The more strides the receiver takes with his arm extended back, the less likely the exchange will be a good one.

THE BASIC RULES AND PROCEDURES

are fairly straightforward and widely known.

- Lanes all the way. Make sure you know your lane and the order you are running before you go to your exchange zone.

- The baton stays in the middle of the lane all the way around. The two curve runners (legs #1 & #3) will run on the inside part of the lane -to save ground- and will carry the baton in their right hands. The straightaway runners (legs #2 & #4) will favor the outside of the lane carrying the baton in their left hands. This right-left-right-left sequence, as well as the inside-outside-inside-outside positioning of the runners, is most critical for good alignment of the runners as they pass the baton and prevents heels from being clipped and outgoing runners being tripped. These positions also keep the baton out of harm’s way; yes, the stick is sometimes knocked out of a runner’s hand!

- The baton, not the receiver, must be in the 30-meter exchange zone when the pass is made. (The 10-meter acceleration zone has been annexed) Know the rules pertaining to marking your “go marks,” whether with tape not always allowed – or with half tennis balls, sometimes only to be placed on the outside line of your lane. Only one tape mark for the pros!

Responsibilities of the Incoming Runner:

- Attack the zone. Do not slow up or relax until the baton is passed.

- Don’t collide with the next runner in the adjacent lane. (legs 1 & 3)

- Share the stick: You get the lower half, the receiver gets the upper half.

- Maintain good running form. Running with your arm extended slows you down. Winding up to make the pass is a waste of time. • Speak first, then reach. Do not give the verbal command of “stick,” “go,” or whatever, and reach at the same instant. Give the command, keep running, and wait for the outgoing runner’s arm to extend, then reach and place the baton in the open hand.

- Do not release the baton until you “see” it into the hand of the outgoing runner. The baton should never be dropped!

- Stay in your lane, but don’t worry about running out of the zone- you are allowed.

- Always look back before exiting the track, someone may still be running behind you.

————————————–

Dennis J. Grady, USATF Level II Coach

Sprints/Hurdles/Relays (revised Jan. 2022)

Responsibilities of the Outgoing Runner:

- Step off the distance (determined after repeated practice) to your “go” mark. Place your mark, usually half a tennis ball or tape. Return to your starting position inside the exchange zone. You must be inside and remain there when the gun starts the race. Use a two-point stance for your start.

This will give you the best line of sight to your “Go Mark” Increase go-mark distances as you progress through your season. Peak!

- Stand in front of the line marking the zone, not on or behind it. Possible DQ.

- Make the incoming runner catch you. Position your feet for a fast takeoff and good line-of-sight to your “go” mark.

- Trust your mark and accelerate 100%, no holding back. (In the 4 x 200 relay, hold back — go at 75%-85%, depending on how strongly the incoming runner finishes a 200m run).

- When you hear your incoming teammate give the verbal command, extend your arm straight back, horizontally, with the palm up, fingers together, thumb extended making a V-shaped target for the pass. Hold steady by pushing the upper arm inward towards your spine. Don’t turn your head or look back; remember, it’s a blind exchange. See Rule 1.

- When you feel the baton, grasp firmly and fly.

———————————————

Pass fast, Pass safely, Pass ON!!