HIS COMMAND OF the 400H over a 12-year international career remains unmatched 35 years after his retirement. From 1976 through ’88 Edwin Moses set a standard Karsten Warholm, Rai Benjamin and Alison dos Santos will need to labor over many future seasons to match.

It seems unlikely they can. Moses in his era that spanned the sport’s transition from an amateur pursuit to professionalism — with the star hurdler active on the front lines of pushing for that change — World Ranked No. 1 for 8 straight years ’76–84, scored a ninth No. 1 in ’87 and rated No. 2 globally in ’86 and ’88.

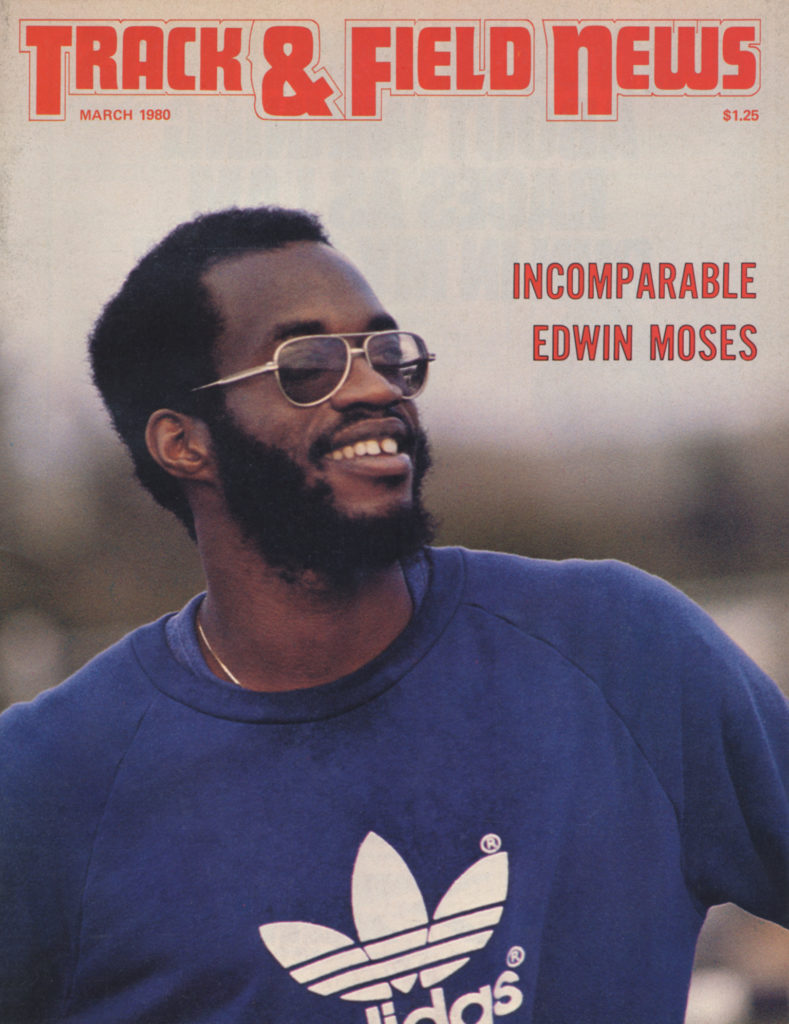

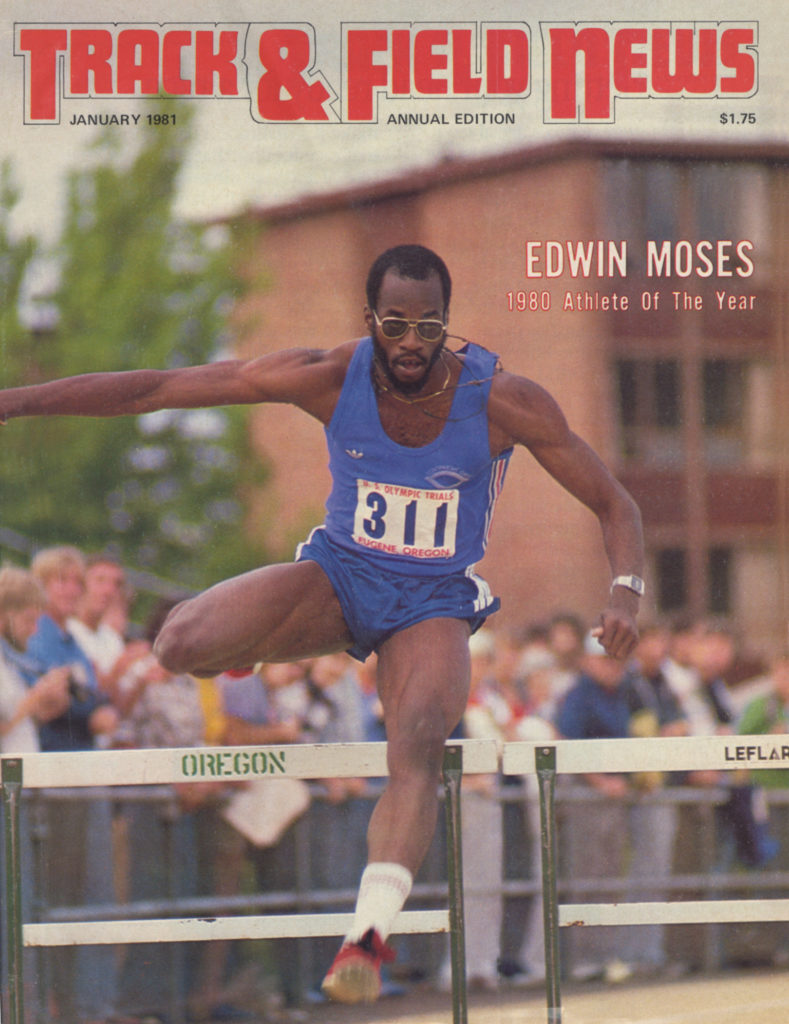

Tabbed easily as T&FN’s 400 hurdler of the 20th century as well as our first 75 years, Moses’ competitive record included “The Streak,” an unparalleled skein of wins without a loss. Our March 2000 issue included this brief summation of his achievements:

“Nine years, nine months, nine days: over that span, the master of the 400H won 107 consecutive finals [122 races overall] 1977-87. The ‘76 and ‘84 Olympic champion counted among his string of wins world titles in ‘83 and ‘87. He set a total of four WRs in his career and was boycotted out of the ‘80 Games when he was a virtual certainty to defend his title.”

Possessing physics and industrial engineering degrees from Morehouse College and also an MBA, Moses in his post-athletic career has served in important roles including Chair of the United States Anti-Doping Agency, Chair of the philanthropic Laureus World Sports Academy and member of the International Olympic Committee in different roles including on the IOC Athletes and Ethics commissions.

He is an Ambassador for Italy’s Fair Play Menarini Awards. Organized since 1997 by pharmaceuticals/medical diagnostics company the Menarini Group, this annual gala aims “to make young sportsmen and women aware of the importance of becoming champions fairly, counting on one’s own strengths, adopting a sense of sacrifice, and respecting the rules.”

This, the 68-year-old Moses’ third T&FN Interview, discussion began with a focus on the Fair Play Menarini Awards and, of course, also included plenty of fodder for track fans.

Moses: You better put on your seat belt [laughs].

T&FN: I’m ready. I’ll be honest. Living on this side of the Atlantic, the Fair Play Menarini Awards is not an event I’ve been aware of. I’m curious about what motivated your involvement?

Moses: I’ve been involved for almost 20 years now. When I was the chairman of the Laureus World Sports Academy, I was asked to be a part of it. I’ve been to at least 10 or 12 different versions of it, going back to 2003, 2004.

T&FN: This year’s Awards ceremony was held in Fiesole. How was that event?

Moses: It was fantastic. You know, the thing about it is that when you go to the events, there’s a lot of fine Italian cuisine and great wines and a great opportunity to be around athletes that you really don’t know from around the world. The cities are just spectacular. We’ve been in Cortona, which is a walled city on top of a little mountain — all kinds of different places. This year, it was actually held in an old Roman coliseum.

And the program was just spectacular, visually. The weather was perfect, and it’s a really good evening of sociology, sports, entertainment, people involved in government and politics and all kinds of different areas. But they have a special recognition for sports, athletes internationally, Italian, all over the world.

I was there years and years ago with Jonah Lomu, who was a great rugby player from New Zealand, and Tommie Smith. We’ve been trying to get a lot of the colleagues that I know from the Laureus World Sports Academy. We’ve been trying hard to get [gymnastics legend] Nadia Comaneci, but this year it was her mother’s birthday. She was in Europe, but she couldn’t be there on that weekend.

It’s a fantastic opportunity to get together and have a three- or four-day long weekend. There’s some great categories to be awarded [16 in 2023]. If you can hack in to get live Italian television, it’s live. They have a fantastic panel where we’re talking about sports and participation and careers live to a television audience. That’s very spectacular.

T&FN: Coming at it from a non-Italian perspective and being an advocate for fair play in sport, among this year’s awardees was there any story that you found particularly interesting or inspirational?

Moses: There was one young lady, Larissa Iapichino, who — I actually competed at the same time as her mother, Fiona May. Fiona was a long and triple jumper [and 3-time world champion outdoors and in] from England, and she now lives in Italy. Her daughter is one of the top long jumpers that competes in the Diamond League, World Championships [5th in Budapest] and all that. So it was really good to see that kind of legacy continuing.

T&FN: Before we move on to track & field, would you like to distill your thoughts on the Fair Play Awards and why they are important in today’s sports world?

Moses: Well, I’ve always been an internationalist when it comes to sports. You know, being one of the huge global superstars in the ’70s and ’80s gave me a really unique view of the world through sports.

And track & field was probably — actually, it was bigger than Formula 1. Back then international tennis wasn’t quite as consolidated as it is now. Track & field was one of the top sports in the world. So I loved having that experience and bringing it to the organization.

There’s also my philanthropic work with Laureus. We do projects all over the world. We grew from six projects in four countries, to over 200 projects. And I don’t know how many countries now — 60 or 70. We started off with two donations of a half-a-million dollars and during my tenure we raised like 130 million euro and distributed that money for hundreds of projects. We had the opportunity to make an impression on over 2 million kids.

So I’ve always been an internationalist when it comes from sport, because that’s the life I grew up in from age 21 through the remainder of my life, and that’s all I know.

T&FN: That’s great. We need more of that these days. Of course, I’d also like to hear your take on the current state of track & field.

Moses: Track and field? I’m not directly involved with the sport because of my position with USADA. We have an ethical wall between what we do and what everyone else does in sports. So I’m not directly involved. I haven’t been to any board meetings, I can’t be a member of any sports federation, anyone who’s under the jurisdiction of USADA. We have to stay away from that.

T&FN: I’d guess you must catch some of the championships and other major meets on television. Over the last 5 years 400 hurdlers, both men and women, have been on a roll. What do you make of that?

Moses: The hurdles has been given a new lease on life. And, quite frankly, I’ve been waiting a long time to see how fast people could go. I think the equipment has a lot to do with it — the new tracks and the new shoes. I wish that I had had a chance to run under those conditions.

The tracks that they use now would’ve been banned when I was running, and most certainly the shoes. I think that has a lot to do with the big time differentials between when I was running and what they’re running now.

T&FN: Have you ever spoken with Karsten Warholm, Rai Benjamin or Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone?

Moses: I did a consultation with Karsten back in 2017 when he was running 48.2 — up in Norway at the Bislett meeting. I sat down and had lunch with him and his coach. And they were asking me all kinds of questions and what I thought it would take to run fast, what kind of training, everything.

So I’ve consulted with him amongst other athletes. Delilah Muhammad, I looked at some video with her. And also Shamier Little. I’ve gone over video with her and broken down their races and so forth.

I was up in Norway with Karsten in January in his hometown at his indoor track meet, the first one he had put on in 3 years because of COVID. I went up there to interview him for a documentary that’s being done on my life. So I went up with the film crew. I send him text messages and what not.

Also I’ve spoken to [Alison] dos Santos last year at the World Championships because we’re both with adidas. I had a chance to talk to him about racing and running and training and dealing with all that.

So I’ve been behind the scenes talking to athletes to the extent that I can. I’m not supposed to be coaching them, which I’m not, but just exploring and explaining to them what’s going on in the race and how I approached it. And also how they’re dealing with the equipment and what that feels like and so forth.

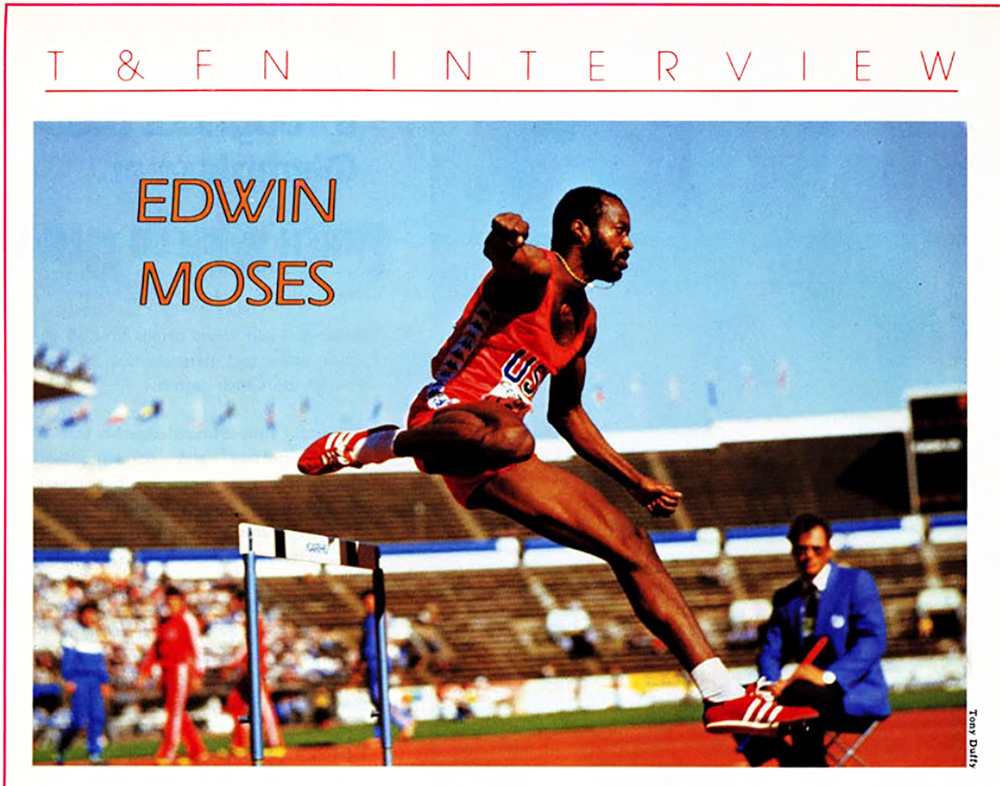

| PREVIOUS MOSES INTERVIEWS | |

| Click on images to read | |

|

|

T&FN: During your career you had a reputation for having dialed in the race pattern with an engineer’s precision. Karsten goes out so hard. He alternates legs and a number of these athletes are doing that. Femke Bol alternates far into her races, as does Sydney.

Any thoughts on race pattern and what you’re seeing these days?

Moses: Well, all the coaches are teaching them that you have to run like Moses did — run very, very aggressively.

Unfortunately for me, I went out fast and then I didn’t have to continue through the sixth, seventh, eighth hurdle, because I was already 10 meters ahead at that point in the race. So I didn’t have to adjust my race to use 12 steps when I was experimenting with it back in the early ’80s because it really wasn’t necessary.

But I think they have a mechanical advantage with the shoes that they use and the tracks as well. [Track manufacturer] Mondo said they designed a track to reduce times by 2% overall for everyone. And we saw that become apparent in Tokyo.

I remember people in semifinals and preliminary heats running very close to their PRs and looking up at the clock with disbelief. So I felt like they’re all running my race pattern. It didn’t used to be that way. Everyone runs aggressively these days, and that’s how you get fast times.

I wish I could have run on a track like that. My 47.02 would have converted to a 46.09 with 2% off of it. And that’s probably without the shoes [laughs].

You can’t even relate the times in the last 5 years with the new surfaces and the carbon fiber plates inside the shoes. I have a pair, I’ve seen them and worn them, and it’s a very strange feeling when you’re used to being on the ground to be elevated 9 millimeters up and you have a plate in the back of your shoe. It keeps your foot in the optimal position whether you get tired or not. So that’s where the time differential’s coming from.

T&FN: Did you actually get out and run a little bit in that pair of modern spikes you have?

Moses: Yeah. I was on Morehouse’s track. It’s a brand new surface. I was out there with the crew doing some footage for the film, and I just said, “I’m gonna be at the track. Let me just bring my old shoes and new shoes and see what the difference is.”

I was afraid to run in the new shoes because I would’ve probably cramped up in the calf. It’s so radically different in terms of the biomechanics. So I didn’t play around with those too much because my calves would’ve been screaming the next day. I know it because of the position that they put you in. It’s very different than running flat with very little up under your foot.

T&FN: What do you do to stay fit these days?

Moses: Power walking. I have bicycles. I do a lot of calisthenics, yoga, the same kind of stretching that I did [in competition days]. I use that very effectively. I used that to get rid of probably having to have surgery for a ruptured disc. It took me 12 years to work myself out of it, but I kept going. Didn’t use any opioids, thank God. It took years to stretch my way out of it to the point where I’m at a zero for pain on a daily basis versus a 7 to 9, like every day for like 12 years.

T&FN: Sounds like you still hew to aspects of your training?

Moses: I diet. I really don’t even call it a diet. I just monitor my food. I have a garden where I have all the herbs, oregano, thyme, rosemary, cilantro. I grow tomatoes and squash. I have figs and blackberries.

I eat the same way that I did when I was running, and I don’t need 5000 calories a day now. If I eat 2000, that’s more than enough for me based on how much I expend.

I was 178, 180, 183 [lbs, 80–83kg] max when I was running. I just got off the scale 30 minutes ago. I’m like 187 right now. I’ve kept myself mean and lean, and everything’s fresh. I eat from the garden, and I cut and shop for every meal. And I don’t eat out a lot.

It’s a lifestyle thing. It wasn’t really so much about, I have to have a diet and I have to concentrate on what I eat every day. I just enjoy cooking. I’ve been cooking since I was in college all the time. I cook all kinds of meals. If I want to make pasta, for example, I go get the tomatoes. I’ve got the basil, I’ve got the oregano and I make everything from scratch. Every day is organic meats, free range, corn fed. I don’t eat anything out of jars, nothing with preservatives in it. And that’s been a savior for me. I mean, that’s a healthy way for me. It’s just a lifestyle. I don’t even have to concentrate on it.

T&FN: The current generation of athletes on average seems to understand the importance of nutrition, but in years past many athletes I interviewed talked a lot about fast food.

Moses: They’d be in the Olympic Village eating McDonald’s. But I was just never into that. The one thing I wish I would’ve done earlier — you probably remember the Juice Man, the old juicer. That was like the first commercial juicer that came out. I’ve gone through probably a dozen of those things in my life. I wish that I had been juicing more back then. I go to the store just to get fruits and vegetables to juice. I think from a metabolic point of view, it’s been very helpful.

T&FN: You were a trendsetter with many of these modalities.

Moses: I also had a very good physical therapist, which I would go to every day, injured or not. So any little knot or pain or soreness, ice baths. I was the first one to do ice baths back in the early ’80s. When people were hearing about it, and there were articles written about it, everyone thought I was crazy. Now, baseball, football, basketball, every sport, every athlete, that’s a routine part of their program

Heartbeat monitors, I was the first one to use those. I got my first one back in 1981 from Polar in Finland. I had one of the prototypes and used that. So all of the things that I was doing 40 years ago are now routine: PNF (proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation), plyometrics, all those kinds of things that no one was doing. I was doing those things way back then. Now they’re routine. So I was way ahead of my time.

T&FN: You coached yourself. That’s very atypical. Why did you choose that approach?

Moses: Because I studied physics and engineering. I took biology, I took chemistry. I wanted to be a doctor. So I knew physiology and what was required. And I did an extensive amount of reading when I was in college on the Krebs cycle — the sugar, oxygen, all that kind of stuff. I was well aware of that.

I tailor-made my program so that I was all natural. Didn’t need to take steroids, never thought about it. And I knew that with my program, it was state of the art and that no one else could do what I did on the track and in training.

Other than that, no one made the sacrifice holistically to compete at the highest level for the longest period of time ever.

T&FN: Surely you must have had a college coach at Morehouse?

Moses: He was more of a chaperone because he didn’t know anything about track & field, Coach Lloyd Jackson. We recruited him because they were gonna cut out the track program in 1975. There was gonna be no track program in 1976. They had already made that decision, the coach had quit.

We recruited Lloyd Jackson from — remember the old CETA [Comprehensive Employment and Training Act] program? We got the CETA program and the president of Morehouse to agree for them to pay him the salary to be a chaperone so we could have someone of age, an adult who could rent cars, get hotels and travel with us.

But he knew nothing about track & field. He ran track & field but he didn’t know the details of running hurdles. Fortunately, one of my classmates was a state champion in the 120-yard high hurdles in Ohio. And we had a guy who was a state champion in Alabama in the 400, state champion in Georgia in the 800, some good cross country guys. We had a good set of guys but we just didn’t have a coach. So Lloyd Jackson took me through ’76 and ’77, and then he left in ’78, which was my fifth year. I didn’t have any eligibility left.

So from ’78 all the way through the end of my career, I didn’t have a coach. But even when I was at Morehouse, I got up in the morning, ran across the country, ran around the school, found a golf course — we didn’t have a track so it was not easy for us to be able to train. I went to a golf course and did cross country training up and down hills, lots of stretching, really developed my own program because I loved the sport of track & field and I wanted to get better.

T&FN: A lot changed for you, and the sport, in 1976. You went from a little-known hurdler at an HBCU Div. III school to setting your first World Record in winning Montréal Olympics 400 hurdles gold that July.

Moses: Going into ’76, my goal would’ve been to get the Olympic qualifying standard. I figured that that would be the pinnacle of my career. (Continued below)

T&FN: So you went from nowhere in what became your signature event to the pinnacle in just a few months. Later came the longevity of the streak. Amazing achievements of two different kinds.

Moses: Ultimately, I stayed in track & field longer than people that were a lot better than me, but I just loved the sport and the incremental improvement that you could make. I went from a 47.5 [400] to a 46.1 from the end of one season to the beginning of the next. So that’s like 1.4 seconds. I liked that. And once I got down to 46, I said, “Wow, I could run 45, maybe 45.5 or 6.”

I just kept going at it and running from behind and catching guys that were a lot faster than me. I ran from behind to condition myself. Our relay team was like a 3:18 [quartet] and I’m running 44.5, you know, catching up, being 50 yards behind [laughs]. So I just ran myself into condition really.

T&FN: How fast were you in high school?

Moses: I ran the 120y highs. I won the Dayton Relays my senior year [1973]. I ran a 15.1, which was my best time, and my best 440 was 51.3. But [at Dayton] my senior year I won the high hurdles and beat the guys that finished No. 1 and No. 2 in the state. But I pulled a muscle that same night running the sprint medley relay, and so my whole senior year, I didn’t get any better than that. But I knew I was good.

I was not able to get a scholarship, I was unrecruitable. And then my freshman year in college I was running like a 49.5 or something like that, and I think I got my highs down to like a 14.3 or 14.2. So I just kept improving little by little. Three years later I was Olympic champion.

T&FN: I want to ask you about a tale I heard to the effect that one year at NCAA Div. III Nationals you raced a hurdles heat in cold, pouring rain and met with disaster. I’m sure your competitors that day remember the occasion. Do you?

Moses: That was ’76 at the NCAA Division III in Chicago. I fell, my glasses fogged up. I think I threw ’em down. I couldn’t see anymore. And I ended up hitting the tenth hurdle. I got up and ran a 52.8 or whatever it was. But I finished 4th in my heat, and therefore I didn’t go to the final the next day. And you had to place 1st or 2nd in the final in order to qualify for the NCAA Division I.

But I think it was a blessing that I fell because I really didn’t need three more races, and then the AAU [now USATF Champs] and then the Olympic Trials. So it was a blessing in disguise.

T&FN: World Records, world titles, even Olympic gold medals, across the 49 events on the current global championships program, athletes achieve all of the above. These are tremendous achievements.

But uniquely you put up “The Streak,” 107 finals (122 races) without a loss in the 400H. Did the streak become a burden or was it strictly a point of pride and inspiration?

Moses: I didn’t even think about the streak, to be honest with you. I never even thought about my competitors. I knew who they were. I knew what they were capable of. But more important than that, I knew what I was capable of.

So my whole thing throughout the whole streak was, It doesn’t really matter what anyone else does or how close anyone gets or how close a race is. The only thing — and I learned that from losing to Harald Schmid in Berlin — is I have to be prepared all the time. As long as that’s the case, I will outrun you to the tape. It didn’t matter who it was. (Continued below)

T&FN: When was it that the media awareness bubbled up?

Moses: When I got like halfway to Harrison Dillard’s streak, which was 82 races at the time [sprints and hurdles competitions in 1947–’48]. When I hit 41, people started talking about it, but I never paid attention to it at all. I just knew that if I’m ready, if I’m prepared, just go out and do your thing.

If you have to think about what you’re gonna do when you’re on the start line, you’ve already screwed up. So I was just waiting for the gun to go off and just run and do what I was capable of doing. I never thought about it.

Even after Danny Harris beat me, I went out with the same attitude. You know, this guy beat me one day when I was sick. If there would’ve been another 5 meters, I would’ve come back and beat him. He just got lucky that day. But I had to race him 2 weeks later to get on the ’87 team at the USA Championships. So I didn’t even think about losing.

When I was running and making my way to the top, I always lost. I never won. Even in high school, I was like 5-7/ 117 (1.70/53) my junior year, and I was one of the smallest guys when everyone lined up. I was a little kid out there, but I never quit. And I always would catch up at the end of the race. When the big guys got tired, I was still churning. That attitude followed me throughout my whole career.

I started at the back and I can say throughout my whole career, no one ever beat me twice. Even going back to college when I first started getting better and running at the SIAC, our conference level, running against some guys that were really, really good running 13.6 and 13.5, and guys running 46.3s and 46.4s. Once I beat them, they never beat me again. I kept that going for my whole career.

T&FN: Is there one race that stands out in memory as your sweetest victory?

Moses: I think the sweetest one was… Well, two: ’84, of course, winning at the Olympics at home, and then the ’87 World Championships, because I really shouldn’t have won that race. I had been sick and missed like 3 weeks of training all of August leading up to the World Championships in Rome.

I had gotten food-poisoned the week that I ran Danny Harris. I was sleeping all day and up all night — diarrhea, vomiting, and it kept coming back. So it jumped back on me again, I had an intestinal infection in August so I was out.

The way that I ran that race was the only way I could’ve won it, just running a suicide race from the front and make them catch up and make mistakes. Those two races are the ones.

The one where I regret not following through was Lausanne 1981. I ran 47.14. The World Record was 47.13 and I slowed up. I could have run under 47 that night. I had quite a few races where I would slow up and run 47.1 47.2. Not knowing that I was running that fast, I wish I could get those back.

T&FN: Your USADA role necessitates some distance from certain aspects of the sport. Even so, are there ways in which you feel track & field is or isn’t where you had hoped it would be by now back when you were competing?

Moses: In 1981 I presented an 8-point plan for track & field for really improving the sport.

T&FN: This would have been just as the IOC, WA (then called the IAAF) and USATF (then called TAC) had hashed out some level of above-board professionalism for track athletes, yes?

Moses: We got it clear for athletes to be able to make money, not only in track, but in other sports as well. Subsequent to that, I was appointed to the IOC Athletes Commission, but I presented an 8-point plan in order to really professionalize the sport of track & field — contracts, to break up the meet promoters’ cartel, legalize payments and to form a collective bargaining unit on behalf of the athletes to be able to negotiate against the federations for TV rights, sponsorship rights and effectively have a union.

That’s the one thing that I still think is missing. And that was 1981. I’ve got the minutes and the whole program. I looked at it last week from my archives. Forty-two years later it still hasn’t happened.

In 1983, ’84, I was making as much as the top NFL quarterbacks. That was before the salaries rocketed in the NFL. I was making more than probably most NBA players.

As sponsors, I had Kappa, I had adidas, I had Kodak, I had lectures, I had IBM, all kinds of deals. But it was kind of like I was under the radar. I wasn’t like some of our other athletes who were bragging about how much they made.

And I wish that track & field had been able to keep pace with that, because now if you play in the NBA and you’re on the bench, you’re probably making $2–5 million. You have to be absolutely a world champion, Olympic champion to be able to accomplish that in track & field.

We lost a lot of years because the athletes did not want to, and they chose not to, participate. We haven’t had a union to represent the athletes against the federation.

T&FN: It seems our sport’s superstars choose to work their own deals. Usain Bolt, or any current blockbuster athlete, has little incentive to negotiate in solidarity with all those other athletes across 50-plus events, including those outside the Olympic slate.

Moses: It’s no different than tennis. The tennis players did it and their prize money skyrocketed. What the athletes need is they need to be represented. They need to be protected even from their agents, which an organization like tennis does. Your agents have to be certified, certain parameters have to be followed. You’re protected from the federation.

It’s very, very selfish, but that’s why 95% of the athletes are struggling all the time. If you’re not in the top 8 in the world, your new contract is minimal. You’re not making $300,000 a year if you’re qualified to be in a final at the World Championships, in most cases. Some are but in general, if you’re not in the top 5 or 8, the shoe companies give you a minimal contract. Or if you don’t remain in that top 5 or 8, then you get cut.

I talked to so many athletes who made the team in Tokyo, they don’t even have contracts now and could barely get a lane in a race at a Diamond League meet. The athletes have to be protected from the agents and the federation, and they have to take that upon themselves. There’s no retirement fund, there’s no health insurance. All of these things can be done collectively. Tennis has done it. And look at the sport of tennis today. We were more popular than tennis, except for the big 4 tournaments back then.

No one was making money in tennis back then. No one until they collectively bargained and had a union and had some protection against everyone.

Because at the end of the day, the agents can stay at home, the federation can stay at home, but if the athletes stay at home, no one has anything.

I think the athletes have to figure out that they could do better with a union than with their agents representing them. Because the agents, they don’t go for a piece of the television rights or the marketing rights. All they’re doing is hoping that their athlete can get a commercial endorsement and collecting money for them to run track meets and getting them contracts.