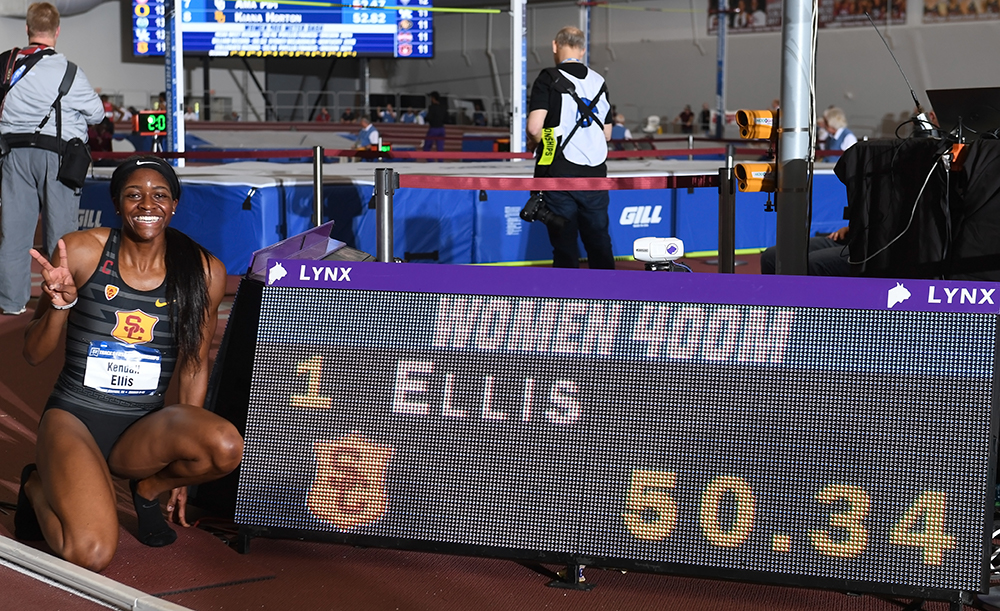

“MAN, IT WAS TOUGH.” Kendall Ellis had been on top of the world in college, closing out her USC career in ’18 with an NCAA Indoor win in an American Record 50.34, a Pac-12 win outdoors in a PR 49.99, and a runner-up finish at the NCAA Outdoor with a stirring come-from-behind victorious relay anchor. The 49.99 made her one of only 3 collegians ever to crack the 50-second barrier.

The Florida native had hoped for a smooth transition to the pro ranks after that campaign. It didn’t happen. “I think I struggled a lot both on and off the track” she admits. “You know, when you have a lot going on in your life outside of your sport that has a tendency to kind of flow into your career as well, especially because I’m young and I’m still learning to compartmentalize. I think it was taking a toll on me.

“I expected to sign a contract at Nationals, or maybe a month, maybe 2 months right after. That wasn’t the case; I hadn’t signed for almost 6 months after Nationals.”

The pro contract symbolizes an athlete’s arrival on the scene; it’s a de facto acknowledgement that the sport places a tangible value on their efforts. Without that, Ellis was at a loss.

“It was very, very hard on me,” she admits. “No one really knew. I didn’t talk about it a lot. It was kept between my coaches and I, and going through fall training, trying to work hard and accomplish things you want to accomplish, but not having a deal. I had the title, I had the record, I was top 3. I did everything that I was supposed to do and to not get rewarded with the contract immediately when I saw all these other people signing was just a lot for me to handle.”

It affected her workouts: “I was showing up to practice, not really engaged and not really motivated. It took a big toll on my training that showed throughout the season.”

Ellis eventually signed with New Balance in the winter and felt that for much of the ’19 campaign she was playing catch-up. “I was really struggling to run times that I was running with ease in college,” she admits.

When her faith wavered, it was Quincy Watts—who has coached her since her college days—who still believed. “I remember all throughout the season, Coach Watts kept telling me, ‘You know, you can still make the team. You can still make the team despite what the times are looking like right now.’ That’s what we kept focusing on.”

At the USATF meet, Ellis snapped into action. Three rounds, three seasonal bests. In the final, she cranked 50.38 for 2nd behind Shakima Wimbley: “Even Coach Watts said, ‘That was like the best series of races you’ve ever had. I’ve never seen you take advice that I’ve given you the day before and apply it so clearly and quickly to the next race.’ That was a really big confidence booster for that season.”

She followed up with a pair of Diamond League appearances, placing 2nd in Paris and 7th at Zürich. Then came Doha’s WC, where she was anxious to do better than her ’17 London travails, where she placed only 5th in her heat but did earn gold for running in the 4×4 rounds.

“London, for me, was a terrible experience, my most embarrassing experience by far,” she says. “I never wanted to feel that way again.” In Doha, she worked to avoid a replay, with mixed results. She made it to the 400 semis, placing 3rd, but just missed a trip to the finals. She again won gold for relay duty in the heats.

While plenty of athletes would be satisfied with two straight Worlds, two straight golds, Ellis is not quite there, explaining, “Of course, I wish I had made the final—at the bare minimum—and got on the podium. I was happy in the sense that I had done better than in 2017. But it’s disappointing when you don’t make the final, because that’s what you’re here for. That’s the plan. I will say I didn’t beat myself up over it, like I had in the past.”

It has been a long road for Ellis since she got her start as a sprinter in Ft. Lauderdale as a 7-year-old, even though there are conflicting accounts of how exactly that happened. “If I tell the story, I told my mom that I wanted to travel. And she was like, ‘I don’t know where you think you’re going.’ And the next thing I remember is I was running on a track and I was like, ‘This is not what I asked to do!’

“If she tells the story, I came home from school and I was telling her that I was oh so fast and I was beating all the boys. She was like, ‘OK, let’s do something about it.’ She found a club and signed me up.”

She retired from track for a few years at age 11. “I was like, ‘I’m good. I’m enjoying not having to go to practice.’ And then I found myself missing it. That’s kind of how my relationship with track has always been. I enjoy it; I’m good at it, but it’s hard. The sport is very hard and if you are not all in, then you’re not going to see success. If you’re not willing to give all you have day in and day out, then you don’t need to be doing it.”

As far as the media is concerned, the arc of Ellis’s story culminates in The Relay Leg. Her ’18 NCAA anchor for the Trojans—a 50.05 carry that brought her team from 5th to 1st, also winning the team title—has gone viral as an inspirational video, with various YouTube versions totaling more than 5 million views. “I don’t think I’ve had an interview since that race where it hasn’t been brought up,” she says.

“I have mixed feelings about it. It brings attention to our sport, which is always needed. I appreciate people who reach out to me and say they watched it. Like, I love that. But on the other hand, I don’t think that’s my biggest track and field accomplishment. I am so much more than a relay leg. I hope that is not the biggest thing that I accomplish in my career.”

Currently training in LA with superstars Rai Benjamin and Michael Norman, plus new addition Candace Hill, Ellis says that when the quarantine hit, “We definitely adjusted some things. In terms of intensity and quality, that didn’t go anywhere, but we definitely had to change some of the workouts just because the access to facilities wasn’t there.”

A large part of coping with difficult times, she says, “is just understanding that we’re mostly on the same boat. Nobody’s really able to compete the way they want to. Nobody’s really able to train the way they want to. We’re all going through it. I’m in a hot spot for the virus right now. We don’t know what things are going to look like in 2 weeks.”

While she’s waiting to see if she’ll get a chance to race this year, the 24-year-old Ellis continues to work on her MBA (through the program USATF has set up with DeVry University), while she is relearning how to play the piano, “flying through books,” and hanging out with her training partners, who are close friends off the track.

Ellis looks ahead with a steely sense of realism and determination. She explains her mindset thus: “Granted the Olympic team is a highly different ball game, but for the sake of argument, I know how to make a team. But every team I’ve made so far, I came home with nothing. You know how to get yourself in the door, but you’re not doing anything when you get there.

“I’m no longer satisfied with saying, ‘I was there,’ because I have nothing to show for it. So these next few years, I want to make sure that I’m coming home from these championships with a medal or multiple medals in my hand, because that’s what we’re looking at now, how do I get myself on the podium?”