THERE WAS ONCE A TIME when big-city invitational indoor track & field meets were part of nearly every U.S. sports fan’s consciousness. It was a traveling road show of high-skill athletes seamlessly conducted among NFL playoffs and the long-haul seasons of the NBA and NHL.

In just 9 short weeks, the undercover carnival — almost exclusively the province of men — trekked to nearly 2 dozen North American cities. There were contests in Portland and Pocatello, Saskatchewan and Albuquerque, Philly, Seattle and Los Angeles too. Boston, Oakland, Houston, Louisville, San Diego, Vancouver, Cleveland, San Francisco and more.

Legendary Sports Illustrated scribe Tex Maule said, “There are few spectacles in the world of sport to compare with an indoor track meet for color and movement and excitement.”

He was right of course. The up-close pageantry unfolding upon a tight wooden oval, nestled practically in one’s lap, and an infield just out of arm’s reach, called for a much fuller immersion inside, than the same sport conducted outside. The grunt-then-thud of a shot putter’s heave melded with the rolling thunder from the incessant pounding of boards. Tobacco smoke wafted down from the rafters with the din of close-quarter crowds oohing over missed vaults, and aahing for close clearances. Bedlam often ensued from the fight for position on turns that are banked.

He was right of course. The up-close pageantry unfolding upon a tight wooden oval, nestled practically in one’s lap, and an infield just out of arm’s reach, called for a much fuller immersion inside, than the same sport conducted outside. The grunt-then-thud of a shot putter’s heave melded with the rolling thunder from the incessant pounding of boards. Tobacco smoke wafted down from the rafters with the din of close-quarter crowds oohing over missed vaults, and aahing for close clearances. Bedlam often ensued from the fight for position on turns that are banked.

In the winter of 1971, one half-century ago, the indoor sport was still near its zenith, setting the stage for some of the best depth of performances that the sport had ever seen.

The legacy of indoor track hearkens back to the sport’s inaugural event held on Manhattan’s Upper East Side in November of 1868. Hosted by a fledgling NYAC, the first indoor amateur athletic games were staged under the tarpaulin-patched roof of the soon-to-be finished Empire City Skating Rink.

In the winter of 1971, one half-century ago, the indoor sport was still near its zenith, setting the stage for some of the best depth of performances that the sport had ever seen.

It was a season of some tongue-twisting pronunciations for American ears, with athletes named Gianni Del Buono, Kjell Isaksson, Henryk Szordykowski and of course Jean-Louis Ravelomanantsoa. A season with a pair of Australian Kerrys, who spiced up the 2M, and of gunslinging big men whose shots were heard around the world. It was a season for flashy newcomers along with a prior king’s return from exile.

While the show got off to an inauspicious start on the tight 136.8y (125m) circuit in Saskatoon, it wasn’t until two weeks later in College Park, Maryland, that the season began in earnest.

Highlighted by the big-time sprinting debut of a 27-year-old leukemia researcher, the Cole Fieldhouse crowd was all abuzz over the 60y dash. Dr. Delano Meriwether, who played sax, not tracks, in both high school and college, crouched at the start alongside stars like Mel Pender (who had tied the World Record of 5.9 in the heats), Ivory Crockett and Don Quarrie. Adorned in gold swimming trunks, white hospital shirt, and a pair of striped suspenders the neophyte was off to an atrocious start, when suddenly, midway through, he pulled even, and then outleaned Captain Pender — 6.0s by both — for a most unexpected win.

Highlighted by the big-time sprinting debut of a 27-year-old leukemia researcher, the Cole Fieldhouse crowd was all abuzz over the 60y dash. Dr. Delano Meriwether, who played sax, not tracks, in both high school and college, crouched at the start alongside stars like Mel Pender (who had tied the World Record of 5.9 in the heats), Ivory Crockett and Don Quarrie. Adorned in gold swimming trunks, white hospital shirt, and a pair of striped suspenders the neophyte was off to an atrocious start, when suddenly, midway through, he pulled even, and then outleaned Captain Pender — 6.0s by both — for a most unexpected win.

Unexpected, that is by all but Dr. Delano, who came in having previously announced, “Hey, I can beat those guys” while watching them on TV that past summer. Later, when asked about his uniform choice, the first Black man ever admitted into Duke Medical School explained, “My swimming trunks give me a sense of speed,” and that he wears suspenders, “because women who go to track meets might be entertained by a fashion show.”

And although later that evening Olympic gold medalist Lee Evans raced to a 500y WR of 54.4 while earning the meet’s Outstanding Athlete award, and Tom Von Ruden lowered the 880 WR to 1:48.5, all that the lucky attendees could talk about was the sport’s most colorful man. Over the course of the ’71 season Meriwether would race in 7 top-tier meets. He won at CYO and at Boston, finished 2nd 3 times, and 3rd and 5th once. Undoubtedly, his attire was garish, but the good doctor proved that his astonishing velocity was for real.

As the circuit of ’71 headed west to the Cow Palace, just outside of San Francisco, in excess of 13,000 fans were elated by the return of one of the sport’s biggest names as Jim Ryun reemerged from his self-imposed 19-month hiatus from competition to dip his toes back into the mile wars. Ryun had not stepped on a starting line since the ’69 AAU Outdoor Championships in Miami, where he stepped off the track midrace.

As the circuit of ’71 headed west to the Cow Palace, just outside of San Francisco, in excess of 13,000 fans were elated by the return of one of the sport’s biggest names as Jim Ryun reemerged from his self-imposed 19-month hiatus from competition to dip his toes back into the mile wars. Ryun had not stepped on a starting line since the ’69 AAU Outdoor Championships in Miami, where he stepped off the track midrace.

Without stiff competition, the Kansan grabbed the lead with 4 rotations to go. The recipient of a 2-lap standing ovation, Ryun blazed the final 440 in a swift 56.4 for a back-in-the-saddle 4:04.4 victory.

Four weeks later, on the fast red boards at the San Diego Invitational, the 23-year-old Ryun’s comeback continued. Although 50y back while splitting a 2:01.0 first half, Ryun rolled 59 for the third quarter. Still in just 4th with 2 to go, he skillfully slipped past Dick Quax and early leader Chuck LaBenz and eventually John Mason. Ryun closed yet again in 56.4, good enough to tie Tom O’Hara’s 7-year-old WR of 3:56.4, a performance that surprised even Ryun.

Grinning ear to ear at the postrace press swarm, Ryun politely excused himself to have a gander at the ballyhooed 2-miler. All season long Kerry Pearce and Kerry O’Brien had battled one another for “most awesome Aussie” honors in both the 2- and 3-mile runs. Pearce took the deuce in Saskatchewan, San Francisco, Millrose, Boston and Seattle. In the last, Pearce tied his own indoor WR of 8:27.2. Coming in he had held off the steeplechase WR holder O’Brien 8:30.0–8:30.8 in Inglewood.

After a rabbited first three quarters, the Australians got down to the business of trading leads while towing ex-Yalie Frank Shorter in their wake. The PA announcer recited 4:11.9 at the mile and advised that they were on record pace. At 7:22 with just 440y remaining, it was clear that a new mark was imminent, but by whom, and by how much, was anyone’s guess.

After a rabbited first three quarters, the Australians got down to the business of trading leads while towing ex-Yalie Frank Shorter in their wake. The PA announcer recited 4:11.9 at the mile and advised that they were on record pace. At 7:22 with just 440y remaining, it was clear that a new mark was imminent, but by whom, and by how much, was anyone’s guess.

With three laps left, O’Brien took over from his countryman, and this time for good. Sprinting wildly over the final circuit, O’Brien ripped off a 56.0, while recording a brilliant 8:19.2, the fastest time ever, indoors or out. Pearce too kicked home nicely (57.7) for the runner-up spot in 8:20.6, as Shorter managed 8:26.2, good for an American Record. When asked afterwards to what he owed such a breakthrough, O’Brien cited the arena’s cutting-edge no-smoking policy and the Pro West track’s highly banked turns.

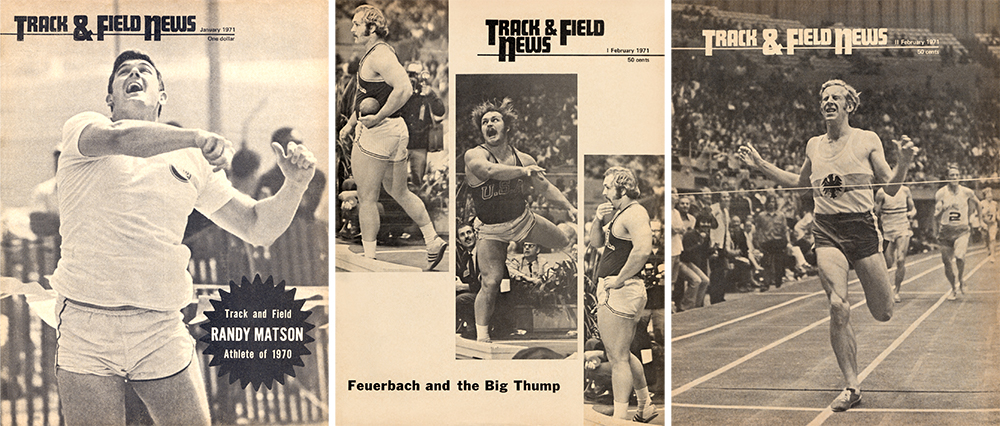

No synopsis of the ’71 season would be remotely complete without reportage of the fireworks from the infield. In a battle of shot-putting heavyweights, 1970 T&FN Athlete Of The Year Randy Matson and upstart rival Al Feuerbach traded blows in 8 explosive mano a mano contests.

When the year started, the indoor WR stood at 67-10 (20.67). When the smoke cleared from the season’s epic duels, Matson’s best-throw-per-meet averaged a hefty 68-2½ (20.79), while the challenger, Feuerbach weighed in with a 67-4 (20.52) average. In every single contest, Matson matched or surpassed Neal Steinhauer’s old WR.

But while Matson won most of the battles, Feuerbach won the war. At San Francisco’s All-American Invitational the Emporia State alum upped his PR with an eye-popping 68-11 (21.00) WR heave, relegating Matson’s 68-8 (20.93) mark to status as the longest-ever non-winning put. It was not the sort of consolation prize that Randy had in mind.

But while Matson won most of the battles, Feuerbach won the war. At San Francisco’s All-American Invitational the Emporia State alum upped his PR with an eye-popping 68-11 (21.00) WR heave, relegating Matson’s 68-8 (20.93) mark to status as the longest-ever non-winning put. It was not the sort of consolation prize that Randy had in mind.

And the hits kept coming, as Isaksson twice set new WRs in the vault. The busy Swede’s first was a 17-7¾ (5.38) at the LA Times meet on February 12. In March he was in Bulgaria for the European Champs, where Wolfgang Nordwig beat him with a WR 17-8½ (5.40). But less than a week later Isaksson was back in Cleveland, reclaiming the mark at 17-9 (5.41) in the year’s undercover finale.

Alas, the major metropolitan indoor meeting road show is merely a distant memory. There is but one of the old-timey contests remaining, the Millrose Games. As the last man standing, said indoor contest moved in ’12 from NYC’s Madison Square Garden to the 168th Street Armory, when attendance dwindled from sellout crowds of 18,000 spectators to less than a third of that tally. We really miss you, indoor track, and may you rest in peace. □