NAME ANOTHER LIKE HIM, in any event. Dick Fosbury, the ‘68 Olympic high jump champion who passed away in March, stands alone in the modern sport’s history for having revolutionized the technique with which his event is practiced.

Every fan today has seen the “Fosbury flop” and no elite high jumper uses any other technique. When “Fos” debuted it the flop was radical.

While it’s true Debbie Brill, a ‘72 Olympian and the Canadian women’s recordholder to this day, independently developed a virtually identical style, the “Brill Bend,” as a teen jumper in the same era, Fosbury in 1968 took his then-idiosyncratic method golden at the Games in Mexico City.

“‘Flop’ quickly became a misnomer,” as longtime T&FN staffer Jon Hendershott wrote in our October ‘89 issue weeks after the 8-foot barrier fell.

This is how Hendershott — who on his typewriter banged out the two stories below as the history was being made — distilled the revolution 21 years after Fosbury rocked his event.

“In 1968 the 21-year-old Oregon State junior won the NCAA title and made the Olympic team, then astounded an international TV audience by topping an Olympic Record 7-4¼ (2.24) to strike gold.

“Today, 21 years later, the flop (by now a generic term and no longer capitalized) is the universal high jumping style and has carried Cuba’s Javier Sotomayor over the magic 8-foot barrier.”

Hendershott again from the same ‘89 retrospective:

“Fosbury evolved his revolutionary style as a prep in Medford, Oregon. Never adept at the straddle, he had a best of just 5-4 [1.62].

“But he experimented with bending his lead leg and turning his lead shoulder toward the bar. The more he did, the more he flattened out in his clearance. The first time he tried the wrinkle in a meet, he cleared 5-10 [1.78].”

Fosbury’s Oregon State coach, Berny Wagner, told Hendershott, “His Medford coach, Dean Benson, tried to get Dick back to the straddle but soon realized this new style worked best. So he left him alone.

“And when he came to OSU, I tried to change him back, too. I even suggested to Dick that he try the triple jump! But before his soph year, he lifted weights for the first time, got stronger and in our first meet, he cleared 6-10 [2.08]. “I showed great coaching genius by realizing right then that suddenly I didn’t need another triple jumper.”

Fosbury, Hendershott wrote, “was also lucky in that he wasn’t the only one thinking backwards.”

Fosbury: “Debbie Brill was developing the style independently in Canada at the same time. If she had had the great year in ‘68, then maybe today we would talk about her ‘Brill Bend’ and nobody would have heard of the flop.”

Hendershott again: “But his style was everything except a flop in ‘68. That dizzying year was a small slice out of his life, but Fosbury — quiet and humble then as he is today — knows how significant it was, too.

“‘As time passed, I realized some of what I did was remarkable,’ he says. “That has helped to motivate me in everyday life: take the drive behind those athletic achievements and translate it into other areas [as a president of the World Olympians Association, founder of an Idaho engineering company, and a public speaker and author].’”

PROFILE OF A CHAMPION

That Fosbury Flop

by Jon Hendershott

Dick Fosbury has turned high jumping upside down.

As if any more proof was needed, Fosbury proved again at the NCAA Championships and the Los Angeles Olympic Trials that the “Fosbury Flop” is the most sensational form development in track & field in the last decade.

The boyish-looking Oregon State junior who created — and perfected — the back-to-the-bar, head-first high jumping style cleared an amazing 7-2¼ (2.19) to annex the outdoor collegiate title in a new meet record. Just as amazing is the fact that he didn’t miss in the entire competition until the bar was raised to 7-3¼ (2.22). If there were any skeptics left who didn’t believe the flop, Fosbury certainly proved himself and his style in grand style at Berkeley. At Los Angeles, he continued his winning ways, clearing 7-1 (2.16).

Just as quickly as he turned high-jumping upside-down, Fosbury showed his style was of champion caliber. He first topped 7-feet indoors this winter, eventually reaching 7-1¼ (2.165) and also collected the NCAA indoor crown. It took him the entire spring to reach 7-feet outdoors, but he has cleared that magic height when it has counted most. He won the Pac-8 Conference title at 7-0 (2.135), his first 7-footer ever outdoors, and then reached his career high in the NCAA.

“I was surprised to do so well,” Fosbury said after his NCAA win. He is tied with Otis Burrell and Mike Bowers as the fifth-highest American jumpers ever and is an equal tenth on the all-time world list. Quite a list of achievements for the only man to clear 7-feet backwards.

After winning the LA Trials, Fosbury took one try at 7-3 (2.21) but then retired, explaining later, “I just didn’t feel very well today. It was nothing in particular, but my legs felt tired and I couldn’t psych myself up. I really haven’t felt up to par since the NCAA so I’m grateful I was good enough to win.” In the biggest meets this spring, Fosbury has proven he can win with his flop and then some.

How did he create the “flop”? Well, if you’ll pardon the expression, it was as easy as lying down. After learning to high jump in junior high school, Fosbury reached high school and found himself still struggling to clear 5-4 with the old scissors style. He then reasoned that he might do better by lowering the center of gravity by laying out on his back The first time he tried this wrinkle in a meet, he went from 5-4 to 5-10. He had found his style.

Simply speaking, the flop is the reverse of the straddle. Fosbury starts his approach run straight into the bar but then gradually swings to the left until he approaches the bar as a straddle jumper does. Any similarity between the two styles ends there.

“I take off on my right, or outside, foot rather than my left foot,” Fosbury explained. “Then I turn my back to the bar, arch my back over the bar and then kick my legs out to clear the bar.” He lands on his shoulders and head and usually does a somersault out of the pit to end up on his feet

“It’s really simpler than the straddle,” he continued. “There are less moves near the bar and you expose only the width of your body rather than the length so the chances of hitting the bar are much less.” Even Fosbury is intrigued by his creation, though, for he added, “Sometimes I see movies and I really wonder how I do it. But I never could get the roll and I’m not going to switch now.”

By his senior year at Medford, Oregon, High School, Dick was up to 6-7 and he unveiled his style nationwide by winning the National Junior Championships. When he ventured to Oregon State, coach Berny Wagner asked him to try the roll. “I just never had the coordination jumping from the opposite side,” Fosbury recalls. “Besides, the roll is so complicated, there are so many things to think about during the jump.” He agreed to try, though, and for six months experimented with the conventional style. No luck. He was a born “flopper” so it was back to his favorite style.

As a sophomore, he upped his best to 6-10 and placed 5th in the NCAA outdoor meet, a disappointing performance to the young innovator who had aspirations of 7-feet. Then came the indoor season and high jumping’s revolution began. In his first meet, Fosbury jumped 6-10.

Then at the Athens Invitational in Oakland, Dick flopped into the national and world picture as he sailed over 7-feet on his second try at that height. He nearly leapt that high as he bounded out of the pit, hands to his head, a broad grin signaling his elation. He had finally proved his style could carry him over that magic mark.

“Whenever any athlete breaks the barrier of his event, whether it is a 4-minute mile or 7-foot high jump, he feels pretty emotional,” Fosbury explained. “I never thought of myself going that high so when I finally did, it was the greatest moment of my career. He went on to clear that magic height in the next five consecutive meets, getting his best of 7-1 at Louisville and collecting the indoor college title with his final 7-footer. He didn’t compete in the AAU due to an armed services draft physical, delayed to then because of an injury suffered in high school.

“When I jumped in high school, none of the schools could afford foam rubber landing pits,” he explained, “so I would have to jump into sawdust pits. Landing on my neck and back so much compressed two vertebra in my back.”

Even the propect of a sore back hasn’t kept athletes from trying the flop. More and more athletes are taking a fling at the style, some with surprising results. One Oregon high schooler’s story is similar to Fosbury’s in that he couldn’t clear 5-9 by rolling but topped 6-4 in the first meet in which he flopped. Bill Elliott of Texas went one better. A 6-2 conventional jumper, he cleared 6-6 with the flop. A St. John’s jumper, only 5-7 tall who has cleared 6-8 with the straddle, has made 6-1 with the flop and a teammate, a pole vaulter who never cleared better than 5-7 with the roll, has done 5-10. Fosbury’s own Oregon State teammates also have had some success with the style. Steve Kelly and John Radetich (both 7-0 with the roll) have cleared 6-4 while Jeff Kolberg, a 6-3 conventional jumper, also has made 6-4. Many other athletes have reportedly tried the method.

“Only a few kinds of jumpers can use the style effectively,” Fosbury commented. “By the time a jumper is in college he has his style down pretty pat and just works on strength so he won’t make as great a change as this in his style. I’m amazed, too, that so many people have picked up the style just visually after seeing it in pictures or on television.”

“One thing I can say for sure,” Berny Wagner added, “After working on the flop, when the straddle jumpers return to their regular style, they have less tendency to lean into the bar and seem to do as well, or better, in the straddle even though they have been practicing something so different. Also, Dick doesn’t get any lead-leg kick at all and how he manages 7-feet without the supposedly vital lead-leg kick opens some intriguing new areas of thought in the high jump.”

Fosbury’s success with his intriguing style makes consideration of an Olympic team berth this year almost inevitable, but he isn’t quick to declare his intentions “You have to be a certain caliber of athlete,” he ventured. “I figured last year I would just go to the Olympic Trials for the experience but now that I have made 7-feet and higher, I can’t help but think about the Olympics. To compete in the Olympics would be the fulfillment of a dream. I’ve always had, but it’s not as easy as that. Once you say you will try for the Olympics, then everybody assumes you’ll make it. If you don’t, then people wonder why you said anything in the first place. So it’s a relative thing.

If the Olympics are the high-point of a career, does Fosbury think his style has a limit? “I think my only limit now is physical,” he said. “If someone has his style down perfectly, whether it is the roll, flop or whatever, then the only barrier should be his strength. I feel that I am consistent on every jump now, so the only thing holding me back is my physical strength.” It’s hard to believe that anything could hold Dick Fosbury back, for nothing has held him down.

Richard Douglas Fosbury was born March 6, 1947, in Portland, Oregon A civil engineering major at Oregon State, he stands 6-4, weighs 183lbs and has brown hair and eyes. Progression:

| Year | Age | Grade | HJ |

| 1958 | 11 | 5th | 3-10 |

| 1959 | 12 | 6th | 4-6 |

| 1960 | 13 | 7th | 4-8 |

| 1961 | 14 | 8th | 4-10 |

| 1962 | 15 | 9th | 5-4 |

| 1963 | 16 | 10th | 5-10 |

| 1964 | 17 | 11th | 6-3½ |

| 1965 | 18 | 12th | 6-7 |

| 1966 | 19 | frosh | 6-7½ |

| 1967 | 20 | soph | 6-10¾ |

| 1968 | 21 | junior | 7-2¼ |

HIGH JUMP

Fosbury-Flop Loosens Crowd

by Jon Hendershott

Ever since last winter when Dick Fosbury and his unorthodox backward-flop high-jumping style became the rage of track and field, he has electrified spectators, puzzled coaches and beaten opponents with his self-evolved style. In Mexico City’s 1-mile high altitude, he did it all again, flipping over 7-4¼ for Olympic and American records and the US’s first high jump gold since 1956. Fosbury’s competitive performance, his style aside, was simply sensational. He cleared every height he attempted through 7-3 3/8 on his first try, showed supreme confidence by passing 7-1 and came through with an easy clearance of 7-4¼ on his third try to better John Thomas’ eight-year-old US mark by a half-inch. But perhaps the most amazing aspect of all was that Fosbury had every one of 80,000 fans who jammed Estadio Olimpico on the final day of track competition, October 20, captivated.

No announcement was made when he jumped but everyone knew when he was up. After he cleared the bar and plopped into the Port-a-Pit landing on his shoulder blades, the crowd exploded into wild cheers and applause. One German pressman proclaimed, “Only a triple somersault off a flying trapeze with no net below could be more thrilling.” A Hungarian discus thrower who spoke no English still managed a thick “Fantastic” at Fosbury’s every clearance.

And the boyish-looking Oregon State University student responded enthusiastically to the crowd as he grinned broadly, threw up his hands and hopped out of the pit as he cleared each height. He was clearly the most popular winner of the Games. Even the press, usually reserved even at these emotion-charged Olympics, cheered at his every jump.

Fosbury was up against the toughest field ever assembled to do battle for the Olympic title. There were 17 7-footers eligible to compete but the two young Swedes, Bo Jonsson and Jan Dahlgren, stayed home injured and East Ger many’s young Joachim Kirst, with a top of 7-1, finished the decathlon the same day as the high-jump qualifying. Those who were there, though, comprised a tough, talented field.

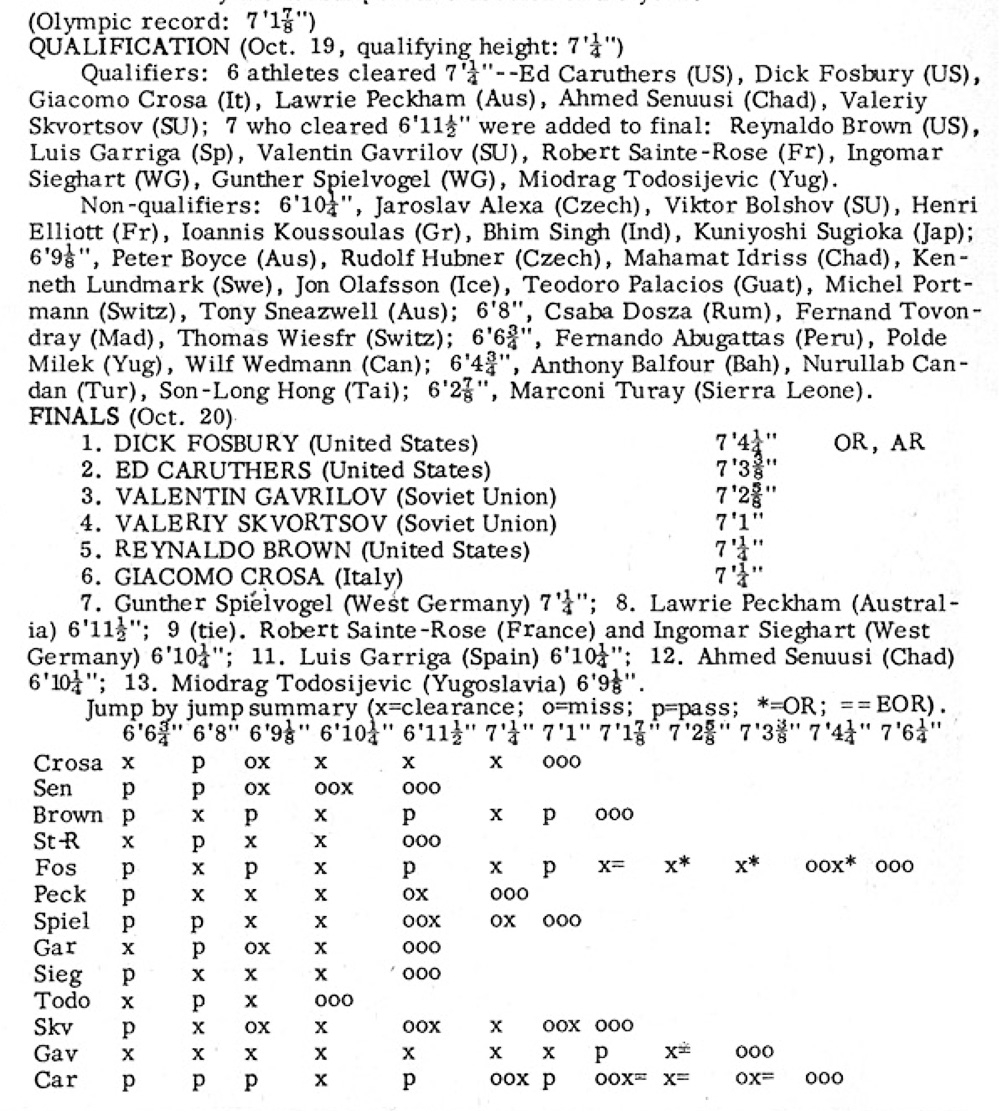

Only six jumpers, Fosbury and Ed Caruthers of the US, Lawrie Peckham of Australia, Valeriy Skvortsov of the USSR, Giacomo Crosa of Italy and Ahmed Senuusi of Chad cleared the qualifying height of 7-4 in the preliminaries, October 19, which had the field of 39 split into two groups, one jumping at the north end of the stadium and the other at the south end. Consequently, seven more who cleared 6-11 were added to the final to get the necessary 12 finalists. Among this group were 17-year-old American Reynaldo Brown and 7-2-plus jumpers Robert Sainte-Rose of France and Valentin Gavrilov of the USSR.

Most notable among those eliminated were Viktor Bolshov, the Soviet veteran who was sixth at Rome and had cleared 7-1 this year to make the Olympics, West Germany’s young 7-footer Thomas Zacharias, Australia’s Peter Boyce, who shared the world lead at 7-3 with the three Americans, im proving Swede Kenneth Ludmark (7-1), France’s little (5-8) Henri Elliott who had also gone 7-11 and Chad veteran Mahamat Idriss.

The finals began the next day under warm sun and bright skies, but the competition was to stretch well over three hours and end in the cool evening. Everyone got over the lower heights with no trouble, while 6-10 resulted in the day’s first casualty, Yugoslavia’s Miodrag Todosijevic. At 6-11, Senuusi, Luis Garriga of Spain, West Germany’s Ingomar Sieghart and Sainte-Rose went out. The Frechman, wearing high-slit shorts similar to Eddy Ottoz’s “bikini” bottoms, showed little of the bounce which put him over 7-2 in practice.

The finals began the next day under warm sun and bright skies, but the competition was to stretch well over three hours and end in the cool evening. Everyone got over the lower heights with no trouble, while 6-10 resulted in the day’s first casualty, Yugoslavia’s Miodrag Todosijevic. At 6-11, Senuusi, Luis Garriga of Spain, West Germany’s Ingomar Sieghart and Sainte-Rose went out. The Frechman, wearing high-slit shorts similar to Eddy Ottoz’s “bikini” bottoms, showed little of the bounce which put him over 7-2 in practice.

At 7-4, the surprising Crosa, the two Soviets, Brown and Fosbury cleared on their first jumps but West Germany’s hefty Gunther Spielvogel needed two and Caruthers three. The Italian and German succumbed to 7-1 while the three Americans passed. Gavrilov popped over in another picture-perfect leap. Skvortsov seemed to hit a snag and barely scraped over on his third try, leaping out of the pit with a jig as the officials tacked 7/8” on.

Now it was strictly a US-Soviet affair. Brown missed badly twice but missed by the slimmest of margins on his third try. Fosbury took the full two minutes prior to the jump, building his psyche but clenching his fists this time instead of wiggling his fingers. Then he sped at the standards, was up and over easily. Skvortsov failed to clear his trailing knee twice and on his third jump simply got up and jumped, a beaten man, hitting the bar going up. Handsome young Gavrilov tried some of his own psyching as he passed. Caruthers, like

Skvortsov, missed twice. On his third try, he stared at the bar for a long while before clearing by two inches. He grinned broadly as he sauntered from the pit; he was the third man to tie Valeriy Brumel’s Olympic record within minutes.

The medal winners were now decided as the bar was raised to 7-2 5/8. Only their order remained to be determined. The three wasted no time, each clearing easily on his first attempt. Up went the bar to 7-3 ⅜. Fosbury again took the full two minutes, ignoring the relay runners who wandered throughout the jump area. He again drove powerfully at the bar, was up and over as the lead-off men of the 4×100 relay strained at the first exchange. For the first time, Gavrilov seemed tired and he missed all three times, coming closest on his second try. Caruthers missed once, but then cleared cleanly on his second. The bar went up to 7-4¼, a half-inch above Thomas’ American record set in 1960. Fosbury didn’t get his heels over quick enough in his first jump and the officials marked his first miss of the entire competition, preliminaries and finals. Caruthers missed his first try and each man couldn’t get over on their second jumps.

So now it was the last chance for each man. The marathon runners were entering the stadium, through a tunnel just across the track from the jump area. Fosbury stood in his trancelike pose. “I think about floating over the bar,” he said. Again he stood for two minutes, then rocked back on his heel and sped toward the bar. He drove powerfully off his right foot, arched his back and simply sailed over.

At that exact instant, US marathoner Ken Moore entered the stadium as the first Yank. Moore saw Fosbury clear the American record height and he threw his arms in the air, danced a jig step and shouted congratulations to Dick. The crowd roared with delight at the antics of the two young Americans.

Caruthers had one final chance. He took longer than usual before jumping — -he had been one of the promptest jumpers all day — and showed his consistent power in take-off but hit the bar on the way up. He lay for a moment in the pit, his eyes closed, but then jogged out and over to his elated teammate.

Caruthers had one final chance. He took longer than usual before jumping — -he had been one of the promptest jumpers all day — and showed his consistent power in take-off but hit the bar on the way up. He lay for a moment in the pit, his eyes closed, but then jogged out and over to his elated teammate.

It seemed almost anti-climactic that Fosbury tried three times at a world record height of 7-6 but didn’t come close on any jump. He was Olympic champion and that was all that mattered. The award ceremony for Fosbury, Caruthers and Gavrilov was the last for track & field and on the stand Fosbury flashed his seemingly ever-present, boyishly impetuous grin. All three waved profusely to the crowd which responded with louder cheers than any during the competition.

Fosbury’s coach, Berny Wagner, pointed out another important factor. “Dick has a tremendously dynamic competitive attitude. It’s one of those intangibles but he has that superb competitive ability to come through when it counts most.” Fosbury had confidence in his ability all along and so did Wagner. Asked several days before how he thought Fosbury would do, Wagner replied frankly, “I think he’ll win at 7-4. Fosbury proved that was no idle boast.

Reportedly, at a press conference that evening at the Olympic Village, a press aide told the assembled scribes, “I’m sorry, gentlemen, but the high jumpers are too tired to come down to talk with you. But the marathoners will be here in a moment.” Yes, it had been a long day for Dick Fosbury and company. Fosbury, a civil engineering student at Oregon State, admitted later he was completely drained after the competition. “I’m as tired as I’ve ever been,” he said. “I’d like a shower and then to see my mother.”

For Fosbury, the victory was a culmination, the epitome of his constant striving to prove that his style was not just the off-beat creation of one man but a real break-through in the event. “It’s a very consistent style,” Dick explained. “Once you master the technique, you can concentrate on developing strength. I think my improvement this year (6-10 to 7-4) is due to weight-training more than anything. I don’t jump that much in practice.” Ten days prior to the competition, he had cleared 6-11 in practice, best ever by an inch — and in only his fourth practice session of the year.

There is no saga quite like Fosbury’s. We’ll leave you with the high jump great’s closing observation to Hendershott in ‘89.

“The name described the style: your body did flop over the bar. Yet a more hidden meaning was contradictory: a ‘flop’ meant failing. It was the contradiction in it that appealed to me. I found it almost poetic.”