IN JOURNALISTIC TERMS, it’s the ultimate moving target. Our efforts to bring you a reasonable forecast on what will happen to collegiate track and cross country in this age of pandemic has been stymied daily by the steady drumbeat of bad news and unforeseen developments. Some of our interviews have been outdated almost as soon as we hang up the phone.

Yet the story is real and it has serious implications: collegiate athletics is facing the biggest challenge in its history, and track and cross country will not be spared.

Most would say It all started with COVID-19. Yet what we’re hearing from college coaches is that existential struggle they face has been a long time coming because the financial foundation for collegiate athletics is not nearly solid enough to bear the weight of football.

Picture it: Div. I sports as the Titanic trying to thread its way through icy waters in the night. Enter the C19 iceberg. The worldwide outbreak threatens to sink everything from finances to schedules, putting college sports underwater in an unparalleled crisis.

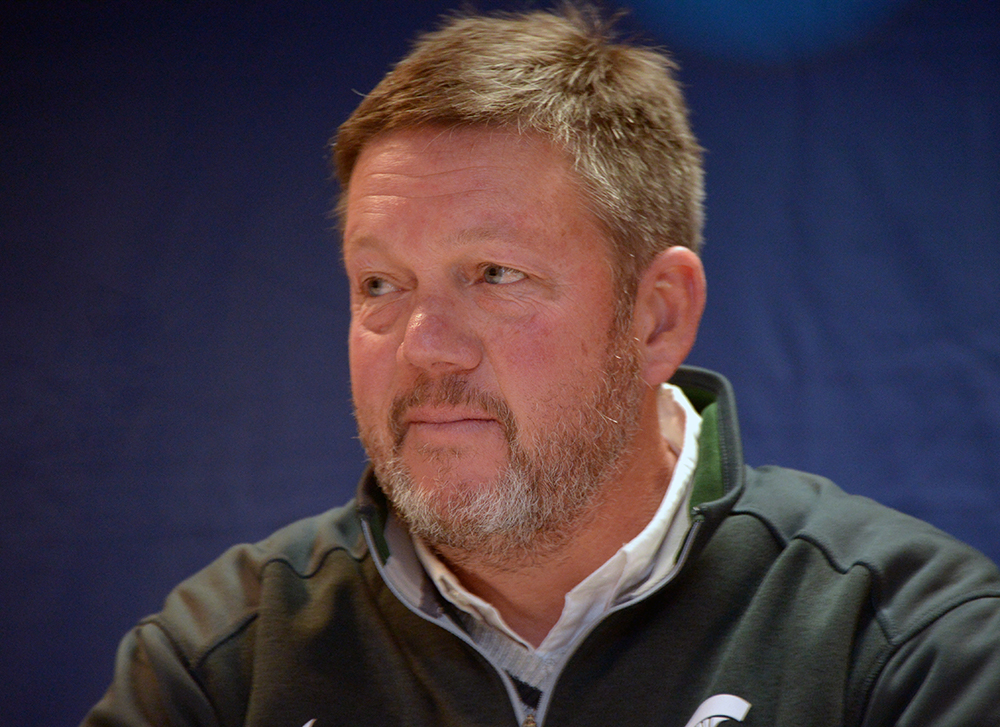

Says Michigan State’s Walt Drenth, “I don’t think COVID caused this. I think it sped it up. The acceleration of our problem is obvious because of how some departments have chosen to spend money. This was inevitable at a lot of schools.”

The shoe everyone’s waiting on to drop is college football. If it doesn’t happen this fall—or even if it does squeak by on some reduced level (empty stadiums, anyone?)—the financial repercussions for some of the nation’s biggest universities will be devastating. It’s estimated that a year without football means an average loss of $62 million for each Power 5 school.

Before that loss even registers, most U.S. colleges are facing increased costs across the board along with sharply dropping enrollment. Boston U is expecting a $96 million shortfall. Penn, $91 million; Arizona, $66 million; Central Florida, $48 million; Kansas State, $37 million, and so on. This is hardly a complete list, and certainly not a list of the biggest deficits. This a quick sampling. Check tomorrow, you’ll find worse.

Was College Athletics Already On Thin Ice?

The concept that collegiate sport is built on an untenable financial foundation means that something had to give eventually. Despite America’s addiction to college football, the fact is that the sport loses money at the vast majority of colleges. The oft-repeated chestnut that football pays for “minor” sports like track is hardly true anywhere. While the schools that participate in the college football playoffs are doing quite nicely, most of the rest struggle.

In 2017-18, for instance, the combined profit of the bowl games that lead to the playoffs was $448 million. That money only goes to the top of the pyramid, primarily the FBS (Football Bowl Subdivision). The FSC (Football Championship Subdivision) schools—which include 12 Div. I conferences, lose an average of $2.4 million per school annually on gridiron operations. The implication is clear: mid-major programs that would never dream of jettisoning their fiscally troubled football teams (“What will the boosters say?”) are naturally looking about for other ways to cut costs within their athletic departments.

Says Akron coach Dennis Mitchell, “It takes a lot of money to compete in FBS football. Group of 5 schools [American, Conference USA, Mid-American, Mountain West, Sun Belt] have a difficult time with those expenses since they are not bringing in as much revenue. As a result they have difficulties paying for other sports on top of the massive expenses they feel are needed to be competitive in football. Lately, since there are sport sponsorship minimums, you get the feeling, and you fear, that the other sports may be there to make FBS Football possible.”

The minimum number of sports the NCAA requires for a school to claim Div. I status is 7 each for men and women (or 6 men/8 women). Back in April the NCAA Council said no to a proposal from the Group Of 5 commissioners to temporarily reduce those numbers, saying it would only consider reductions on a case-by-case basis.

“They asked for [up to a 4-year] break on the sports sponsorship requirement,” says newly retired Duke coach Norm Ogilvie. “Instead of sponsoring 16 sports, we’re going to sponsor, say, 8. Those programs, what are you going to do with the staffs for 3-4 years? You’re not going to furlough them, you’re going to fire them. And they’re going to be gone.” In such a scenario, Ogilvie warns that the teams may never come back: “There’s always such a huge startup cost in anything.”

Strong opposition to the Group Of 5 proposal came from the Intercollegiate Coach Association Coalition, representing 21 “Olympic sports” including track & field.

It remains to be seen how many programs will try to get a waiver this year. In June, after cutting men’s track and dropping below the minimum, Central Michigan was granted a 2-year waiver from the sponsorship requirement. Now Wright State is applying for a similar waiver after cutting three sports.

Yet the pressure to cut teams and costs to protect football runs into a huge barrier in the form of Title IX, which among other things requires schools to offer participation opportunities proportional to the number of males and females in the general student body. More and more, those ratios are shifting towards females. In ’69, some 58% of college students were men. Now that’s flipped, with the Department Of Education reporting that 56% are women.

Increasingly, the survival of all men’s Olympic sports at these schools is at risk. Said one Mid-American coach, “The more you spend on football, the more you have to spend on women’s sports.” And the less on men’s sports that aren’t called football. “It’s just a numbers game. I don’t think any one particular sport is being picked on right now. It’s going to come down to what your percentages are for Title IX.”

The budget cuts will fall on the men’s side. Schools are well aware of the dangers of running afoul of Title IX by cutting participation for women. A flurry of litigation in the ’90s surrounded schools that attempted to drop women’s varsity programs for budgetary reasons. Four separate federal circuit courts ruled against such moves. Still, attempts to cut women’s sports occasionally happen, with one Midwestern school settling a major lawsuit over this last winter.

Yet the heralded “cost-savings” that come with cutting Olympic sports are illusory. When athletics administrators say they are cutting programs for financial reasons, they are almost certainly referring to keeping the school’s expenditures in line with Title IX standards. A cruel truth to the situation is that a fully-funded Div. I or II men’s track program has only 12.6 scholarships, mostly split up into small chunks.

As a result, the average track/XC team member is paying more in tuition than they get in scholarships. The elimination of a program may save an athletic department money on paper, but when the athletes transfer out, the school will tend to lose more than that amount—and it doesn’t show up on the athletic department’s balance sheet.

Some argue that colleges could actually bring in more money if they added sports instead of cutting them—and got away from athletic department accounting that ignores the economic realities on the main campus. A recent report on Sportico showed that some of these schools making cuts could turn their deficits into surpluses by adding sports and attracting more tuition-paying students. Yet that kind of thinking isn’t getting traction in the college world.

Don’t think that the massive endowments that some of our vaunted institutions have will save sports. Most came with strings attached by the original donors, and those strings are usually academic. Even in the case of an endowment that is given to an athletic department (a few schools such as Penn and Stanford have endowed track coaching jobs), the normal annual expenditure of the endowment is no more than 5%, to guarantee that the fund survives in perpetuity.

The Axes Start Swinging

In the C19 financial climate, it didn’t take long for athletic departments to bring out the axe. Akron was first, cutting men’s cross country, a move that sparked a spirited protest and, according to Mitchell, offers from private backers to fund the program. “We’ve got plenty of people who would donate to support cross country. That’s not the problem. It doesn’t cost anything to run cross country. There’s no cross country budget. Cross country doesn’t pay for coaches, cross country doesn’t pay for scholarships. You can run a cross country program for way under $10,000 a year.”

Mitchell, who has been Akron’s head track/XC coach since ’95, says, “I always thought we were a foolproof program, because we were putting people in the stands, we were succeeding, we were bringing more money into the school than we were spending, and we are the diversity sport. Everything you’d want in a program, and then you’re like, ‘Ooh, maybe that doesn’t matter anymore. There are new rules we may need to be aware of.’”

Central Michigan followed Akron with the elimination of its men’s track program (but is going ahead with the construction of a $32 million “champions center” at its football stadium). Appalachian State cut only men’s indoor track. In late June, UConn slashed men’s cross country and reduced its men’s track scholarships.

Brown transformed 11 varsity sports into clubs, including track & cross country. However, supporters of the program pointed out that the optics of cutting the school’s most racially diverse team in the midst of the Black Lives Matter protests were decidedly bad. In a rare success story, administrators reconsidered and reinstated track/XC.

Stanford also discontinued 11 varsity sports, but track/XC escaped that round of cuts. The next day, Dartmouth cut 5 varsity sports (again, track/XC survived). With that news, coaching guru Dan Pfaff, now at ALTIS, tweeted, “Domino theory picking up steam.”

After the Dartmouth cuts, AD Harry Sheehy was asked by the student newspaper if it might be part of a domino effect. His answer: “Yeah, it is, unfortunately. That’s the way it works. I think, when the Ivy League acts on something, that can embolden a whole different group of schools to think about what they’re going to do. As tough as the world is for Dartmouth’s budgets, we’re not nearly as in bad shape as most of the world. A lot of schools’ athletic departments rely much more than we do on revenue generation.”

Most of the coaches we’ve talked to assure us that we haven’t seen the worst of the cuts to men’s track/XC programs yet. “There is definitely a fear in the coaching ranks that there will be more coming, especially if things go badly with COVID,” says Ogilvie.

“I think there’ll be more canceling of programs,” says JJ Clark, Stanford’s coach. “I think it’s possible, yeah.”

“It’s just a matter of time,” New Mexico’s Joe Franklin told the Beneath The Grandstand podcast. “We are absolutely not immune to this.”

“Do I think more sports are in jeopardy if football doesn’t happen?” asks Drenth. “Yes. I think the smaller schools trying to sustain a competitive D1 football program are going to make it very difficult to hold onto other men’s sports.”

Florida’s Mike Holloway, who in his role as the U.S.’s ’21 Olympic men’s coach is doubly worried, adds, “I’m deeply concerned. I don’t know what to expect, no one does. It’s hard to tell, so we’re doing everything on a day-to-day basis. My prayer is that we see no more programs being cut.”

Ohio State head Karen Dennis, herself an Olympic coach in ’00, notes, “I think if football is canceled, at a lot of universities, we might lose track & field programs. I also think that there’s a probability that football won’t be canceled and may be postponed to a different time of the year… It’s a fluid situation. There’s no definitive answer as to whether football is going to be canceled. I do know that here there’s an interest in having football, even if it’s a reduced schedule or it’s scheduled at a different time of the year.”

“They’re picking the low-hanging fruit off the tree now,” says Ogilvie. “I’m not really sure how much of it is a reaction to COVID-19. The uncertainty with the COVID and the economy are giving them a rationale to cut now.”

Is Cross Country Season Coming?

While the conferences will drive the decision of how to handle fall sports, the signals from Indianapolis—NCAA headquarters—president Mark Emmert in July was indicating that cancellation looked like a strong possibility.

However, a late July NCAA Council meeting to decide the issue ended up kicking the can to August. Emmert said in a statement that the NCAA would “continue to thoughtfully and aggressively monitor health conditions around the country and the implementation of the COVID-19 guidelines we issued last week.”

“The health and well-being of college athletes is the highest priority in deciding whether to proceed with our 22 NCAA championships beginning in late November. We all remain deeply concerned about the infection trend lines we see. It is clear that the format of our championships will have to change if they are to be conducted in a safe and fair manner.”

That leaves the decision making, for now, in the hands of the conferences, The four options that they are taking so far can be broadly categorized as stay-the-course, minimize, cancellation, or postponement.

Stay The Course: Ogilvie has concerns on moving ahead, saying, “What are you going to do if athletes start cross country season and they’re not able to finish it [because of a second wave]? Then you’ve got real problems. What do you do there? Indoors has no chance if that happens.”

He adds, “I’m not putting all of the blame on the administrations. If you don’t know what your future looks like, it’s hard to make concrete plans.”

Minimize: The Pac-12 so far is moving ahead with cross country, while restricting some other sports to in-conference competition only. “My cup is always half full,” says Stanford’s Clark, “so I’m remaining optimistic until I hear otherwise. For us, it could go either way.”

The Big 10 and Big East are also going the minimize route, limiting cross country to conference competition, though one Big 10 coach felt that applied only to the regular season, and teams would still be able to compete at Regionals and Nationals. There may be more shoes to drop, as Big 10 commissioner Kevin Warren told the Big 10 Network, “We may not have college sports in the fall.”

Cancellation: The Ivy League moved first, just as it had with the spring cancellations. The loop has taken all events in the calendar year off the table, a move which will affect some of the December indoor meets that take place in the Northeast.

Postponement: Some conferences have announced plans that dramatically revamp the sport’s calendar. The America East, Atlantic 10, Colonial and MEAC (in addition to the California community colleges and high schools) are moving cross country to the spring, with track ostensibly to follow.

Other conferences, including the ACC, Mid-American and SEC, have simply opted for a slightly delayed start. The Mountain West, citing finances, has trimmed its indoor and outdoor championships to 1-day events.

In all of these cases, cross country coaches are having to plan for a season that is essentially unplannable. Drenth, who coached the Michigan State women to the NCAA title in ’14, explains, “We’re making plans and my administration is aware of those plans. They haven’t said we can go [to team camp] but they haven’t said no yet.

“All these are things we’re going to be navigating without any point of reference and not a lot of information. It will be hard to believe that kids will all come back [to school] healthy. I think we have an idea of the variables but I don’t think we have a real idea until we come back and go through all the experiences.”

Drenth, like many coaches, also has to worry about his school’s big fall invitational, an event that typically draws 7–8000 entries, and another 6000-plus officials and fans. This year’s edition is canceled, though he’s exploring the possibilities for a Big 10-only event. He adds, “It would be hard for me to imagine that we have as many kids and parents as we’ve had on the golf course, until we have a vaccine.”

Already several other schools have canceled their flagship harrier events, most notably Wisconsin’s Nuttycombe Invitational. Most others will likely follow, as opportunities for teams to travel out of their regions and compete against non-conference rivals will be severely limited.

Another concern that puts a wrinkle into the plans of many schools is that many of them, like the Big 10 schools, plan to have athletes tested regularly. But nationwide there are a growing number of reports of significant delays in COVID test processing. One lab reporting “unprecedented demand” says its turnarounds have increased to up to 6 days—a number that will only get worse as the expected second wave gets bigger. Some public health experts are suggesting that the limits of testing capacity necessitate tests being prioritized in favor of critical populations, meaning hospital patients and close contacts of confirmed cases go first. Healthy cross country runners, one would think, won’t be at the front of that line.

In the end, the crucial decisions that will affect the sport this fall will be made at a higher level than the athletic department. State health orders and CDC warnings will rule the day. And at least one politician has weighed in on the NCAA’s predicament. U.S. Senator Richard Blumenthal (D—Connecticut) called on all colleges to cancel fall sports, saying, “The Ivy League has taken a principled stand that it’s going to put the well-being and health of athletes first. The bigger football schools, which are dependent on the revenues, may see themselves differently, but my point is, no matter how much a school is a football powerhouse, no matter how big the revenues involved, athletes should be put first.”

What Then For Indoor Track?

There are more effective and less polite ways to characterize the cross country situation, but let’s just call it a mess. Now let’s wade deeper into the morass. Whither indoor track?

With many schools turning to online education in a big way, coaches will face unique challenges in bringing their teams together for practice. Consider also that many schools will be sending students home at Thanksgiving break and not bringing them back until January or later. Others, such as Washington State, will teach almost all of their classes online. How exactly will teams at those schools train for indoor track?

“It probably won’t have a big influence on the distance kids—they’ll just go home,” says Drenth. “It will have a big influence on the kids who aren’t intrinsically motivated, and will definitely hurt the events where technical skill is involved. The pole vault, hurdles, throws, etc., those are going to see the effects.”

Says Stanford’s Clark, “Obviously you want to coach your team, but from a safety situation, it’s better to have them go home. It all depends on what kind of work the student-athletes do when they’re away.”

Buckeye head Dennis is hoping to keep working with at least some of her athletes in person: “I worry about the indoor track season because of the coronavirus as well. At our school, we’re looking at sending athletes home at Thanksgiving and bringing them back sometime in the spring, but my understanding is that student athletes can remain on campus and train. I don’t anticipate all student athletes having to leave campus, particularly if we are preparing for competition.”

And then there is the setting for competitions themselves: typically overcrowded fieldhouses and arenas where the air circulation can be challenging in the best of times.

Holloway sighs. “Indoors will be a wait-and-see process,” adding, “There’s going to be some changes. Maybe you’ll see 1-day meets split into 2-day meets with half the teams one day, then the other half the next. There’s going to be a lot of complaints about how we do things, but before complaints, we need to acknowledge that safety is our No. 1 goal.”

Listening to public health officials—who haven’t been far off the mark with dire predictions of the pandemic’s course—one comes to the inescapable conclusion that C19 is not going to go away until a vaccine is developed. And while it’s not a sure thing, there have been announcements of promising vaccine developments from labs around the world. Yet even if an effective vaccine is developed today, getting it manufactured, distributed and into people in time for a normal indoor track season is quite unlikely.

How Badly Will This Damage College Track?

What will this sport look like in the United States a year or more from now? Without a doubt, there will be more canceled programs. There may be promising athletes who, frustrated with their careers and educations being interrupted, walk away. The eventual effects on our sport are incalculable—and may be dwarfed by devastation to our economy and our nation overall.

“The longterm damage is in the canceling of the programs,” opines Clark. “Will there be more damage beyond that? You might not be able to travel like you used to.”

Building on that thread, we don’t even know where teams will travel to. Last spring, as reported in last month’s issue, we saw the cancellation/postponement of the nation’s top relay meets. In late July, Drake finally pulled the plug on its ’20 hopes. Major meet directors across the board are hoping for a strong return in ’21, but unless an effective vaccine is widely distributed by then, the outdoor season in the United States could look very, very different than normal.

Says Ogilvie, “There just are so many uncertainties, I think it makes it really tough for those kids. I hope with all my soul we can get back to a place close to where it was. There’s so much change in such a short period of time, it’s definitely scary.”

Dennis takes an optimistic stance, saying, “We have to be worried, but I also think that there’s going to be some resolutions and cures for the coronavirus. There’s always going to be an interest in having sports, there’s always going to be kids who want to participate in sports, and once that happens, fans come back, interest comes back, the business comes back. I think the business of athletics is strong enough to have a resurgence and to hopefully have a healthy future.

“I think we’ll be fine. Will we be fine right away? I don’t think so. I think there’ll be some adjustments that have to be made in terms of maybe scaling back of some things, on some expectations budget-wise but I also think that in the long run, it’s going to be a healthy and a robust athletic community. It’s an uncertain time for all of us right now. I feel confident that people are competent enough and compassionate enough to make the right decisions to serve our greater community.”

With similar interruptions and cancellations going on at the high school level, Ogilvie sagely notes that on the other side of this pandemic, colleges may face a crisis in recruiting talent. “The big time to prove yourself to collegiate coaches is outdoor season your junior year. These guys got that taken away from them. That also goes for the collegiate coaches too. Who do I recruit from this high school class of 2021? Do I go off sophomore performances? What do you do if they’re a javelin thrower? Go off something when they were 15 years old? There’s not much you can do about it.”

If there is a talent/recruiting deficit caused by a gap of a year or more in the performance of track prospects, it will only be exacerbated by the bleeding off of upperclassmen. At schools such as Wisconsin, seniors granted an additional spring season by the NCAA have been told to move on. And even at programs that may have left the door open for senior athletes to compete another season, indications are that many are indeed moving on. The lucky ones are turning pro; we typically don’t get press releases on the ones who aren’t quite at that level. In a rare and dire exception, Oregon has reported that 10 seniors and two redshirt juniors—many of them All-Americas or potentials—will not be returning.

A Future Without College Track?

It’s hard to imagine, but a number of people have opined that college sports may not emerge on the other side in any way that we recognize. Sports Illustrated has called the current situation “the economic obliteration of college sports as we know them.” Maybe the big football schools go their own way and leave the NCAA behind. Maybe the future for college track/XC is the intramural running club. And maybe many mid-size and smaller schools, faced with a huge budget contraction, jettison athletics altogether as they rethink their role in American society.

What then? What happens to the talent that needs to be discovered and nurtured but does not have the financial wherewithal to attend college without an athletic scholarship? What happens to the coaches that have to leave the sport because mortgages have to be paid? How does a club-based system even get off the ground when most of the nation’s facilities are owned by schools?

Says Drenth, “We may need to come up with another model in order for track & field—in order for all Olympic sports—to be vibrant in 10 years. I keep thinking there’s got to be a [new] model because kids are going to be leaving high school… maybe the smaller divisions will have places for them to go, but maybe they won’t. And what is USATF going to do if the elite kids start to drift off?

“I’d be interested statistically to know how many of our Olympians were developmental kids that weren’t super-obvious as seniors in high school. The sprints and jumps, those kids probably start out at a pretty high level. There aren’t too many 22-foot long jumpers that end up being 28-foot long jumpers. But you can certainly see a 4:15 boy miler or a 4:50 girl miler turning into an elite. And if those kids aren’t being recruited by the elite schools, where are they going to go? How are they going to be developed?”

At this point, we don’t have the answers. No one does. The crisis facing NCAA track & field is real and it poses a huge threat to the health of our Olympic development programs.

A light at the end of the tunnel? We’ll holler when we see it.