BASED ON research and personal interviews, author Aime Card illuminates the personality of an American icon. Long jump legend Ralph Boston’s incredible life was a story of triumph over adversity off the track as much as on.

RALPH BOSTON, an Olympic medalist in three consecutive Games during the ’60s died Sunday, April 30th at the age of 83. Raised in deeply segregated Laurel, Mississippi, Ralph Boston defied physical gravity, earning his way to college with his outstanding performance in the long jump and hurdles.

Boston became the first man to break the 27-foot barrier (8.23m) in the long jump, earning a medal in three consecutive Olympics, then leveraged his experience to become a beloved sports commentator for CBS and ESPN, and an Assistant Dean of Students at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville.

[Ed: T&FN’s Athlete Of The Year for 1961, Boston World Ranked in the long jump 10 times 1959–68. For 8 consecutive seasons, 1960–67, in which fellow stars Igor Ter-Ovanesyan and Lynn Davies were tough competitors to best, Boston wracked up consecutive No. 1s. In the 110 hurdles he World Ranked twice (No. 5 in ’61, No. 10 in ’63).

He sensationally entered the club of World Record breakers in August, 1960, when he leapt 26-11 (8.21) to add 3 inches to the standard set by the great Jesse Owens a quarter-century earlier. Boston broke the WR five more times in his career, maxing out at 27-4½ (8.35) in ’65.]

Boston’s position as a university administrator was particularly important to him, because he witnessed the school’s integration after his own college degree was earned.

Boston was the youngest of nine children and grew up in Laurel, Mississippi. Everyone in Laurel knew him as Hawkeye. “Before the age of 10,” Boston said, “I looked like six o’clock. Skinny and straight up and down. I had a big head and bulging eyes, so large that I couldn’t fully close them.” His cousin called him Hawkeye because he liked to keep an eye on things, even while he slept.

“Growing up in Laurel was like growing up in any small town in Mississippi in the late 1940s and 1950s,” Boston said. “You didn’t expect much because there wasn’t much around set aside for Blacks.” Boston went to school in a small wood building without heating, using books that were passed on from the white children’s schools when they were either too worn out or out of date to want them anymore.

In high school Boston was a strong student as well as a standout athlete dominating the state in the long jump and hurdles. Today Boston’s accomplishments would have given him his pick of universities, but for Boston, the road to higher education was more challenging. Boston told Tennessee sportswriter and friend Dwight Lewis, “Quite honestly, coming out of Mississippi, my first choice was to attend the University of Mississippi. It made sense for me to want to go there. My family and relatives were taxpayers within the state. It made sense for me to go to a state-supported university which offered the things the traditional Black colleges didn’t offer. It didn’t make sense to me why a resident of that state could not attend a state institution. But of course, I couldn’t in that time because I was Black.”

Instead, Boston went to Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial State College (now Tennessee State University), a historically Black university much farther than he cared to travel from home where he found a new community that expected excellence, and Boston rose to the occasion.

“When I came on to the campus, in the summer of ’57, I remembered seeing Wilma walking around the track with an umbrella when it was drizzling,” Boston said, speaking of Wilma Rudolph, the other iconic track sensation from Tennessee State. While the school may not have had the facilities and opportunities of the flagship state universities of the era, Tennessee State was loaded with elite athletes. “She had gotten hurt; she had pulled a hamstring in the USA/USSR meet in Philadelphia. She was doing her rehab. Until then I had never met Wilma. I hadn’t heard of her then.”

Years later that haunting image was imprinted in his mind, the first sighting of a woman who would become a lifelong friend, a fellow legend. The fastest woman in the world was sidelined from practice, but still she craved the track time, counting the days until she was set free from her injury. It was Boston’s first view of the Tigerbelles, a group of women who were almost universally unparalleled in stature on the track.

While the men’s team was coached separately, they used the same facilities, and Ralph learned his rank as second to the Tigerbelles as soon as he met Ed Temple. “I walked out onto the track, and there were hurdles set,” Boston said. “And I raised them, because they were too low,” being set for the women’s team. Boston heard a voice behind him, “Ph-shew, old buddy, when you finish, you put them back like you got them.” It was Coach Edward Temple, and he wasn’t about to let his team’s equipment be disrespected by the newcomer. “It wasn’t a knock on him,” Boston explained.

He’d have to show some results to earn Temple’s respect.

Boston’s world was just beginning to expand. “Understand, I came from Laurel, Mississippi. As my uncle used to say, nothing happens there but morning, noon, and night.” Boston said. “So, when I came to Nashville and made the team and traveled all around and was able to see other things, other cities, other areas, how people lived. That was a lesson to me. That was wonderful.”

The track at Tennessee State was in rough condition during those years, so sometimes the top runners were invited to use the track across town on Vanderbilt’s campus. The former Governor and United States Senator from Tennessee, Lamar Alexander, was a member of the Vanderbilt track team and remembered sharing the track.

Senator Alexander told Bill Traughber for the Vanderbilt Commodore History Corner, “The fastest and the best guys at that time did not get to go to the SEC, because that was when Vanderbilt and the other teams were still segregated by race.”

Lamar described one of the highlights of his time running track at Vanderbilt was watching the Tennessee State athletes practice. “We just sat back and watched,” Alexander said. “They were Olympians. Ralph Boston was on that team. And even though Kent Russ won the SEC long jump for Vanderbilt that year, Ralph Boston would come over and practice at Vanderbilt and jumped two feet longer than Russ.”

Even though both tracks were in Nashville, one was on the other side of a division that separated the Black part of town from the white. The barrier wasn’t an actual wall, but it might as well have been.

The teams practiced side by side long enough to become friendly, joking around together. Ralph Boston, who rarely met a stranger, watched the Vanderbilt relay team practice. He couldn’t help but tease his new friend, Lamar Alexander.

“Hey, Lamar,” Ralph called out to him, “You know why you’re on that Vanderbilt relay team?”

“No, why?” Lamar called back.

“It’s because they need four guys. Because you are terrible.”

To understand how this joke would land, one has to understand Ralph Boston. The friendliest kid who ever leapt through the sky. He spoke with a wide grin, and it was impossible for anyone who received his attention not to respond in kind.

Both teams sometimes used Centennial Park for distance running, on West End Avenue. The park was and still is a large open space crowned with a full-scale replica of the Parthenon of ancient Greece.

“Near the Parthenon,” Boston said, “there is a stretch of nice soft green grass. I would take off my shoes and run barefoot through that grass. You could do that, and nobody bothered you. I don’t know if you’re allowed to do that now. Nobody said a word to you. They just left you alone, and you did your thing.”

Ralph Boston noted being allowed to run at Centennial Park for a reason. He was well aware that at the time, there were plenty of places he wasn’t allowed to go. The students at Tennessee State had just begun to participate in lunch counter sit-ins led by Vanderbilt Divinity student, James Lawson, along with Diane Nash and John Lewis. Students were beginning to cause “good trouble” but while Boston rooted for his fellow students, he kept his focus on the track and stayed out of trouble. For him, being sent back to Laurel, Mississippi, was too dangerous a consequence to risk.

In 1960 Boston qualified for the United States Olympic team and recalled meeting Cassius Clay, later known the world over as Muhammad Ali.

“I tell this story because it’s one of my favorites and we were friends until he passed. I got off the bus in New York getting ready to get outfitted,” Boston said. “Got off the bus and then I stepped down to the street level. A young man put his hand in my chest. And this, you know, if I lost my mind, I’d never forget this. He put his hand in the middle of my chest and said, ‘Ralph Boston, how do you do?’ How are you doing man?’ And we shook hands. And I said to him, ‘Well, who are you, man?’ and he said, ‘You don’t know me now, but you will.”

Boston said, “Okay, what’s your name?”

He said, “My name is Cassius Marcellus Clay.”

A few weeks later at the Stadio Olimpico in Rome for the Olympic Games Opening Ceremony Boston walked behind Rafer Johnson, the first Black man to bear the US Flag at the Olympics, with the gathered teams representing the United States. Boston said, “I’d never seen that many people in my whole life as we walked into that stadium. Oh, look at all those folks. Wow.”

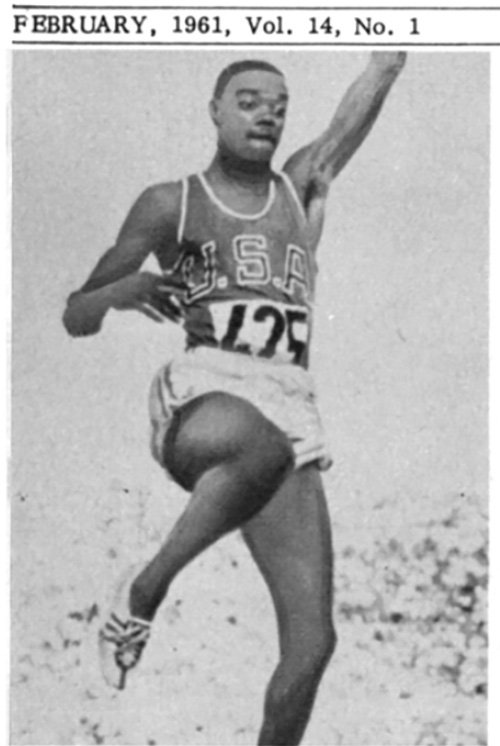

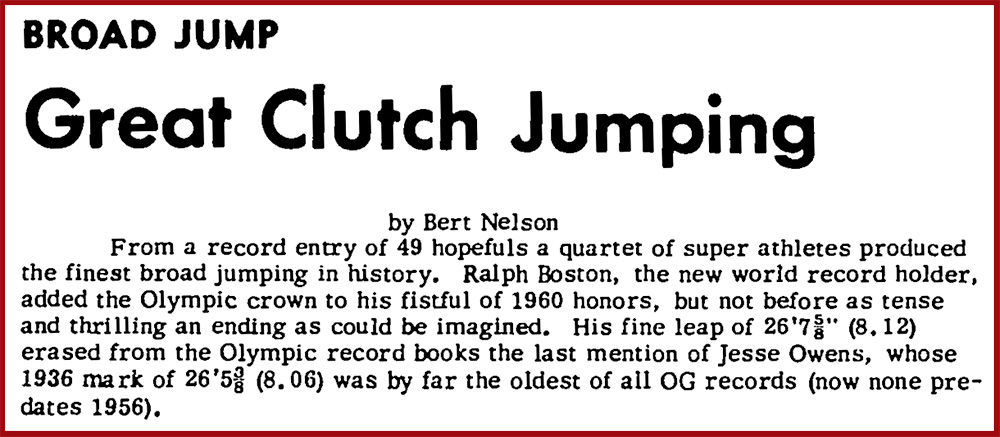

Having ended the great Jesse Owens’s 25-year reign as World Record holder a month earlier, Boston blew through the competition, easily making it to the long jump final which was held just a few yards away from the finish line of the 100m women’s final competition where his friend Wilma Rudolph ran for the gold. Boston’s personal hero, Olympic trailblazer Owens had watched from the stands while Boston jumped closer and closer to Owens’ longstanding Olympic record.

Boston saw Wilma Rudolph cross the finish line for her groundbreaking win and was close enough to call out his congratulations to her over the roar of the crowd.

Boston finished his event with six jumps, reaching his furthest, 26-7¾ on the third try, flying past Owen’s record while Owens was heard to say, “There goes another old friend.” After his jumps, already back in his sweatpants, Boston watched his friend and fellow USA team member, Bo Roberson, take his last jump. It was a great one. Boston wasn’t sure who had reached the furthest yet, but already pounded his buddy on the back for the beautiful jump, knowing silver or gold, they’d each won a medal. In the end, Boston had it, his first gold medal. A win for team USA.

The crowd was so exuberant that after his medal ceremony, Boston had to be “smuggled” out of the stadium, but he still thought he could have done better. “I could have jumped farther,” Boston said to a journalist for The Tennessean, “but I just couldn’t get my steps right. I keep working on them and keep working on them. If I get them right one day, I’ll go farther.”

Boston never quit pushing himself, always knowing he had more to give, and unsatisfied unless he knew he had given everything he had.

An official congratulations was printed in the Nashville Banner for Wilma and Ralph Boston, the newly hailed hometown heroes, stating, “It was for each a personal achievement, calling on reserves of strength, and skill, and fighting heart — the qualities of challenge historically implicit to the Olympiad: but no less do these reflect credit on their school, their state, and their nation. They have honored all three.”

Boston returned to the Tennessee State campus a conquering hero, along with four female classmates on the Tigerbelles team: Wilma Rudolph, Barbara Jones, Martha Hudson, and Lucinda Williams, each returning with their own gold medal.

Boston was asked by a reporter for The Tennessean if Jesse Owens was upset with him about his broken record, and Boston replied, “No, man. He’s a cool cat!” Boston knows of what he speaks. After the 1960 Olympics Ralph “Hawkeye” Boston participated in both 1964 and 1968 Olympics winning two more medals, earning what he jokingly called a “full set” with a silver in 1964 in Tokyo and a bronze in 1968 in Mexico City.

When Boston stood on his final Olympic podium in 1968 behind his friend and mentee Bob Beamon, the pair stood barefoot in a silent protest supporting their friends John Carlos and Tommie Smith who were removed from the games for raising their fists during the playing of the national anthem.

During his Olympic career Boston coached at Tennessee State, then put his personal charm to work becoming a sports commentator covering track and field for CBS and ESPN. The year after SEC (Southeastern Conference) sports were finally integrated Boston worked for the University of Tennessee in Knoxville where he was Coordinator of Minority Affairs and Assistant Dean of students from 1968 through 1975. Boston was inducted into both the National Track and Field and US Olympic Halls of Fame.

“People just loved him,” Dwight Lewis said. “He was a great storyteller.” Boston often spent time with his fellow Tennessee State alumni organizing fundraisers and gatherings, always ready to honor others for their achievements and help entertain the crowd. “He didn’t quit giving,” Lewis said.

Boston died of complications of a stroke at his home in Peachtree City, Georgia, and is survived by his two sons, Todd and Stephen, three grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren, his two sisters, Eugenia Angel and Bettye Beverly, and his brother, Charles. ◻︎